The White House on March 25 announced that Ukraine and Russia had agreed to "eliminate the use of force" in the Black Sea, returning the spotlight to a theater of battle that has been relatively quiet for more than a year.

Throughout 2022 and 2023, Ukrainian strikes against Russian ships, bridges, and even navy headquarters were a regular occurrence, and the neutering of the Black Sea Fleet has often been hailed as one of Ukraine's greatest military feats during the full-scale war.

Although Ukraine's coastal cities and ports still regularly come under Russian missile and drone attack, out at sea, Kyiv was able to carve out its own trade route after Russia pulled out of the U.N. and Turkey-brokered Black Sea Grain Initiative in July 2023.

The corridor has been a lifeline for Ukraine's economy by allowing cargo vessels to sail safely by hugging the coastlines of Bulgaria and Romania while guided by the Ukrainian Navy.

The latest ceasefire agreement is missing crucial securities that Ukraine urgently needs, including protecting its ports from Russian attacks as well as opening up the blockaded Mykolaiv port.

After the ceasefire was announced, Defense Minister Rustem Umerov said Ukraine would consider it violated if Russia moved its warships outside of the eastern part of the Black Sea, as this would be regarded as a threat to national security.

"In this case, Ukraine will have the full right to exercise the right to self-defense," Umerov said.

How Ukraine contained Russia's Black Sea Fleet

After Ukraine reportedly lost all of its remaining surface vessels in the early months of the full-scale war, Russia was widely expected to have a free hand in the Black Sea.

But innovative tools such as Magura and Sea Baby naval drones and domestically made Neptune missiles turned the tide.

Ukraine celebrated its most successful "kill" when the missile cruiser Moskva, the Black Sea Fleet's flagship, sunk on April 14, 2022, after being struck by two Neptune missiles — marking Russia's first flagship loss since the Russo-Japanese War in 1905.

Ukraine built on its successes, retaking key positions like the Snake Island off the coast of Odesa and, striking Russian naval facilities and docked vessels in Crimea with Western SCALP and Storm Shadow missiles.

One of the crowning achievements of this campaign was a devastating strike on the Black Sea Fleet headquarters in Sevastopol on March 22, 2023.

Throughout the all-out war, Ukraine claims to have destroyed or disabled around a third of 80 Russian Black Sea Fleet vessels, including the Rostov-on-Don Kilo-class submarine, Ropucha-class landing crafts, missile boats, and more. The General Staff says that 29 Russian vessels have been taken out of action as of February 2025.

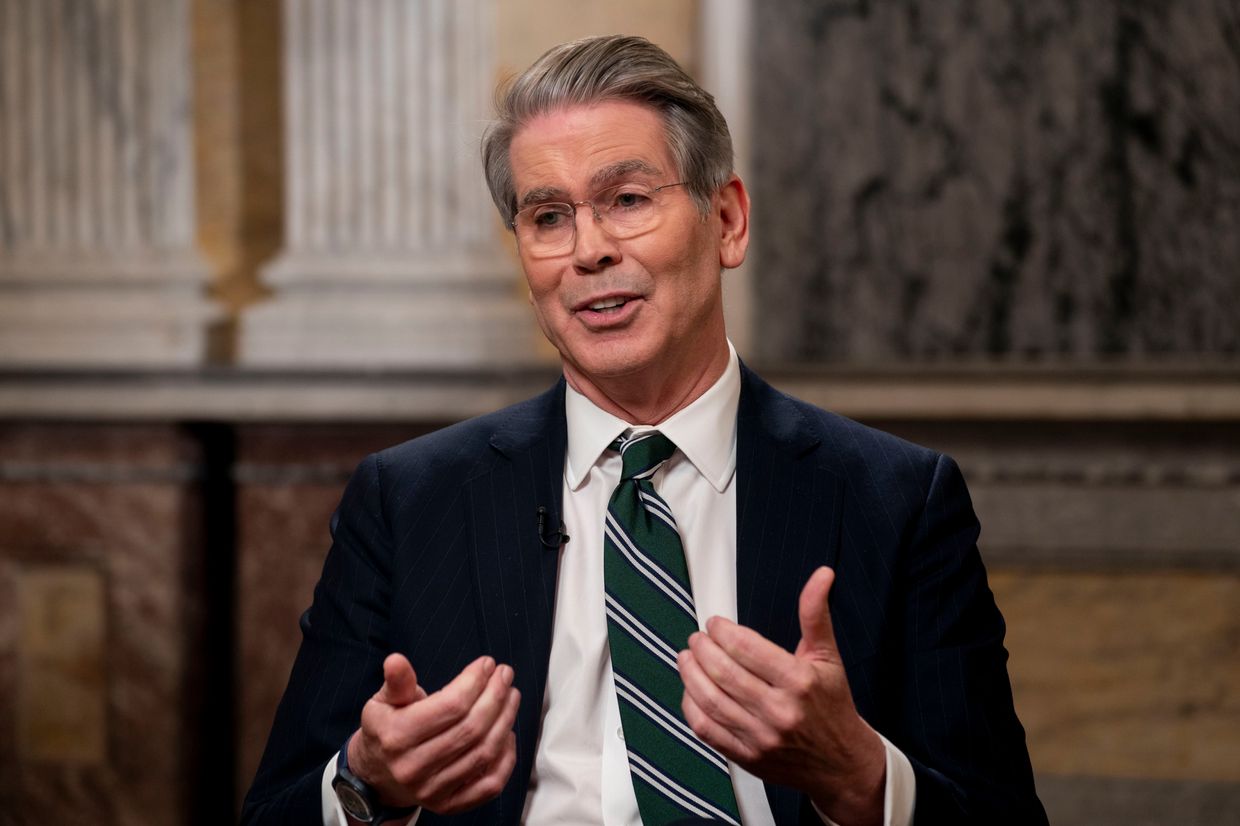

"From the initial perception that the Black Sea Fleet of the Russian Navy was the dominant force in the Black Sea and could do whatever it wants, (we came) to a situation where it is really a very limited factor," Dmitry Gorenburg, a senior research scientist at the Center for Naval Analyses, told the Kyiv Independent.

Russian withdrawal from the Black Sea

To protect its remaining naval assets, in late 2024, Russia began to withdraw its naval forces from occupied Crimea eastward to the Novorossiysk port in Russia's Krasnodar Krai, further away from Ukraine's reach.

"First, they (Russia) lost the ability… to threaten the coastline with amphibious landings in the first few months of the war. And then, the Russian Navy was gradually pushed farther and farther away from the coastline and eventually lost the ability to blockade the grain shipments," Gorenburg said.

As Turkey does not allow Russia to send in reinforcements through the Turkish Straits in accordance with the Montreux Convention, Moscow is unable to replenish its losses. After a sustained Ukrainian campaign, it effectively lost its grip over the Black Sea, allowing Ukraine to resume vital trade lanes.

However, the impact on Russia's global naval power should not be overestimated. Russian fleets operate independently, and the Black Sea Fleet is considered secondary to the Northern or Pacific ones.

A blow against the Black Sea Fleet will not make Russia lose confidence in its Arctic naval assets, security expert Olga R. Chiriac told the Kyiv Independent.

"They're very different in nature. The Black Sea fleet is more of a symbol, a prestige thing, versus the Arctic fleet," Chiriac said.

But there is one region where the Russian Navy felt the sting of the Russia-Ukraine war — the Mediterranean Sea.

Other troubled seas

Turkey's adherence to the Montreux Convention hurts Russia in two ways. Not only does it prevent any belligerent vessels from entering the Black Sea, but it also prevents them from leaving.

Due to its proximity, the Black Sea Fleet has been the logical resource base for Russian operations in the Mediterranean. Russia's naval assets in the region are limited, usually around 10-11 ships, including support vessels, says Sidharth Kaushal, a senior research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI).

Nevertheless, the presence allowed Moscow to project its influence in the Middle East and beyond and cast itself as a global power. Russia could better support its regional allies — by shipping arms, soldiers, and ammunition to Syria's former dictator Bashar al-Assad through the so-called "Syria Express" of Ropucha-class ships, or by launching air strikes against Assad's enemies.

The squadron has also been used to harass and gather intelligence on a much more powerful NATO presence in the Mediterranean.

After the outbreak of the full-scale war, maintaining and supporting the Mediterranean presence fell to vessels much further away, like those from the Baltic Sea Fleet, Kaushal says.

Russia took another major blow in the region when a lightning rebel offensive in December 2024 overthrew Assad. The new leadership reportedly terminated a lease agreement with Russia on Syria's vital Tartus port, Moscow's only foreign naval base, barring those in occupied Ukrainian territories.

Blocked passage through the Turkish Straits and the possible loss of the Tartus base only compound Russia's existing challenges.

"The Russians recognized they didn't have the industrial capacity to build… the sort of the larger vessels that were built during the Soviet era, things like the Kirov-class cruiser," Kaushal said.

"And so they invested much more in smaller vessels, frigates, and corvettes, which they armed very heavily with missiles," the expert added, explaining that these green-water vessels are much more dependent on auxiliary facilities and vessels during long voyages.

Unlike the U.S., which is open to using private contractors to support its maritime operations, Russia constrains itself by relying only on its own infrastructure, according to Gorenburg.

There seem to be only a few alternatives to the Tartus base.

Libya appears to be Russia's first choice. Moscow seeks to pivot its naval presence to territories controlled by Libyan National Army (LNA) Commander Khalifa Haftar, a warlord whom Moscow supported during the country's second civil war.

However, Haftar's forces do not control key ports like Tripoli, meaning that the naval infrastructure Russia used in Tartus would have to be built from scratch, Kaushal points out.

A Russian deal with Sudan to establish a naval base in the war-torn country has also been presented as an alternative to Tartus. Still, the Red Sea base would be geographically distant, separated by the Suez Canal.

"So that combination of factors, having to deploy vessels to the Eastern Mediterranean from further away and potentially losing Tartus, will really strain the Russians' force posture in the Eastern Mediterranean," Kaushal concluded.