EU hits 28 Belarusian judges, propagandists, law enforcers with personal sanctions over human rights violations.

Russian drones again cross into Belarusian airspace in Russia's most extensive drone attack on Kyiv in 2024.

Belarusian political prisoners excluded from historic East-West prisoner swap, sparking despair among Belarusian opposition.

Belarusian police intensify crackdown on exiled journalists, raids 21 family homes.

As other EU states tighten sanctions, Poland says it’s not ready to ban the entry of Belarusian-registered cars.

Four years since the stolen elections, the exiled Belarusian opposition is struggling to help thousands of political prisoners, while also debating opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya's legitimacy.

EU slaps personal sanctions against 28 Belarusian propagandists, judges, prison heads

The European Union introduced new sanctions against Belarus on Aug. 5, targeting 28 representatives of the media, law enforcement, and judiciary over internal repression and human rights abuses.

The new additions to the sanctions list include 13 judges involved in politically motivated trials, including Alena Ananich, who sentenced human rights activist and Nobel laureate Ales Bialiatski, and Viachaslau Tuleika, who passed sentences in cases against people working for the NEXTA opposition Telegram channel and BelaPAN, the largest independent news agency in Belarus.

The list also includes Andrei Ananenka, the head of Belarus’ Main Department for Combating Organized Crime and Corruption (HUBAZiK), as well as two deputies within the structure: Mikhail Biadunkevich and Dzmitry Kovach. HUBAZiK is notorious for its particularly brutal methods of detaining dictator Alexander Lukashenko’s political opponents and home searches that result in damage to property.

“HUBAZiK is one of the main bodies responsible for political persecution in Belarus, including arbitrary and unlawful arrests and ill-treatment, including torture, of activists and members of civil society,” a press release issued by the Council of the EU reads.

The restrictions are also aimed at Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko’s propaganda machine, through sanctions on the director of the state-owned news agency Belta, Iryna Akulovich, the news agency’s previous head and Lukashenko’s former press secretary, Dzmitry Zhuk, and the host of the Senate television program, Mikita Rachilouskiy.

Several prison and penal colony chiefs and state prosecutors are also on the new sanctions list.

As of now, 261 individuals and 37 entities in Belarus have been sanctioned by the EU. Their assets within the EU are frozen, and they are not allowed to enter the EU.

While the Belarusian Information Ministry branded the new round of sanctions “illegitimate,” Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya praised the new restrictions and called for more “targeted actions” against the regime and its enablers.

Since the start of the anti-government protests that erupted in Belarus following the fraudulent presidential elections, the Lukashenko regime has crushed all form of dissent. According to the Belarusian human rights group Viasna, over 50,000 citizens have been detained for political reasons since the 2020 election. At least 5,472 people have been convicted on politically motivated charges.

Lukashenko, under whose leadership Belarus became a close ally of Russia during the full-scale war against Ukraine, said he would run for president again in 2025. The dictator has held the office since 1994.

Five Russian kamikaze drones enter Belarusian airspace as Russia again attacks Ukraine from Belarus

At least five Russian Shahed-type kamikaze drones entered Belarusian airspace during an overnight Russian mass attack on Ukraine on July 31, the Belarusian Hajun monitoring group has reported.

The group says this was the largest observed incursion of Russian drones into Belarus. The first drone entered Belarus at approximately 11:20 p.m. A fighter jet was deployed to intercept it from Baranovichi airfield and spent nearly two hours patrolling the southeast part of the country, which borders Ukraine.

In the following hours, four more Russian Shahed drones entered Belarusian airspace. The majority swiftly exited, but one flew over 260 kilometers, reaching Stolin in the southwest Belarusian region of Brest. There were no reports that any of the drones were shot down.

Previously, four Russian Shahed kamikaze drones that had been launched at targets in Ukraine veered off course and flew deep into Belarusian airspace between July 11 and July 16. Some of them traveled as far as 300 kilometers over Belarusian territory.

Belarusian officials, who say they are bolstering Belarus’ air defense capabilities, have not commented on the situation.

Russia launched its biggest drone attack on Kyiv in 2024 overnight on July 31, launching 89 Shahed-type attack drones at Ukraine, all of which were shot down by Ukrainian air defenses, according to the Ukrainian Air Force.

Belarusian political prisoners left out of historic East-West prisoner swap, sending Belarusians into despair

The recent historic prisoner exchange of Russian agents for Western citizens and Russian activists did not include any of Belarus’ 1,400 political prisoners, sparking an outcry among Lukashenko's opponents.

The largest prisoner swap since the Cold War between Russia, Germany, and the United States saw eight Russians, including a convicted murderer Vadim Krasikov, exchanged for 16 Westerners jailed in Russia and Belarus after sham trials, and Russian political prisoners.

The swap included a German citizen, Rico Krieger, who had been sentenced to death in Belarus for alleged sabotage.

Despite Lukashenko’s involvement in the prisoner-swap negotiations, none of the 1,400 Belarusian political prisoners were let out, causing heated debates and a drop in morale among the dictator’s political opponents.

The exchange was initially supposed to have freed Russian dissident Alexei Navalny in exchange for killer Vadim Krasikov. Following Navalny’s death in a penal colony in February, the negotiations reportedly went on to include several other Russian political prisoners.

Lukashenko’s regime joined the negotiations in July after handing out a death sentence to German citizen Krieger. Following the exchange, the Kremlin thanked Lukashenko for participating in the swap.

Exiled Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya’s office said the Belarusian democratic forces were not part of the negotiations. “We did not participate in these negotiations, and we have limited information,” the office said.

Activist Tatsiana Khomich has why the exchange of Russian political prisoners was not extended to Belarusians, including her sister, Maria Kalesnikava, who lived in Germany for 12 years. In 2020, Kalesnikava returned to Belarus and joined the election staff of opposition presidential candidate Viktar Babaryka. After becoming a force that seriously threatened to end Lukashenko’s 30-year rule, Kalesnikava was sentenced to 11 years. She has been held in an incommunicado prison regime for over 540 days.

Khomich also asked why Mikhail Mikushin wasn't released, who was accused of working for Russian intelligence. Norway could have demanded the release of Ales Bialiatski, the Belarusian Nobel Peace Prize laureate, in return for Mikushin. Bialiatski was sentenced in Belarus to 10 years in prison. His wife, Natallia Pinchuk, says she doubts that his health will allow him to survive his imprisonment.

“For us, this is a signal that neither Belarus nor prisoners in Belarus are a priority. And it’s a very worrying signal,” Khomich.

Poland released Russian Pavel Rubtsov but did not receive any of its citizens in exchange. The Polish-Belarusian journalist and activist Andrzej Poczobut, sentenced to eight years in prison, remains in Belarus.

“This (swap) was an alliance action that we took at the request of the U.S. and President Biden. It regarded exchanges with Russia,” Polish Deputy Foreign Minister Andrzej Szejna told national broadcaster TVP.

Belarusian police conduct 21 raids on exiled journalists’ homes

Belarusian law enforcers have intensified the raids on the homes of exiled journalists, conducting 21 house searches in June and July, the Belarusian Association of Journalists reported on Aug. 2.

“The recent surge in raids is a tactic to exert leverage on journalists and media outlets,” the statement reads. “The authorities are targeting not only the journalists who were compelled to leave Belarus under duress, but also their families.”

Police arrived at the journalists’ registered places of residence with search warrants under criminal cases against them. In some cases, the journalists’ relatives were forced to record videos expressing their remorse for the actions of their family members.

Earlier in July, five journalists focusing on anti-corruption investigations were added to Belarusian and Russian wanted lists. from Buro Media, (Aliaksandr Yarashevich, Aliaksei Karpeka, and Volga Alkhimenka), the founder of the Belarusian Investigative Center Stanislau Ivashkevich, and analyst Siarhei Chaly on the Russian Interior Ministry’s international wanted list.

The Belarusian Association of Journalists (BAJ) is a non-government organization that has been defending journalists’ rights in Belarus since 1995. In 2021, the association was liquidated by the regime. The Belarusian KGB security service branded it an “extremist” organization in February 2023, putting over 1,300 members of the organization at risk of arrest.

The BAJ reports that 37 media managers and journalists are behind bars in Lukashenko’s Belarus. In 2024, the country plummeted 10 positions in the Reporters Without Borders (RSF) annual index of press freedom, dropping to 167th out of 180 states.

Poland decides against banning entry of Belarus-registered cars

Poland is not to introduce a ban on the entry of Belarusian-registered cars, as Warsaw distinguishes the regime of Alexander Lukashenko from Belarusian society as a whole, Polish Deputy Foreign Minister Andrzej Szejna said on PolskieRadio24.

“We don’t want sanctions targeted against regime members in Russia and Belarus to hit Belarusians, who, according to our knowledge, would like to live in a democratic country and be part of the Western community,” Szejna added.

The deputy minister said that after Polish President Andrzej Duda’s visit to China in late June, the number of attacks on Poland’s eastern borders had decreased. Szejna added that Warsaw could still opt to close all border crossing points if the situation on the border deteriorates again.

The European Union’s eighth sanctions package against Belarus, which came into effect on July 29 introduced an entry ban on Belarus-registered cars, mirroring restrictions earlier applied on Russia by EU member states Latvia and Lithuania.

The EU’s decision was based on Council Regulation (EU) 2024/1865, which lists passenger cars as being among the types of goods prohibited in the EU if they “originate or are exported from Belarus.”

The regulation, however, reserves the right for the member states to allow the entrance of such goods if they are intended strictly for personal use by individuals traveling to the EU and their immediate family members.”

Warsaw has accused Belarus of deliberately encouraging migrants to cross into Poland illegally. Warsaw stepped up its efforts to end the artificial migration crisis after a Polish soldier was stabbed to death when trying to stop an illegal border crossing attempt.

4 years after failed revolution

The Spotlight segment provides readers with the historical context of contemporary events in Belarus.

The Belarusian Democratic Forces convened in Vilnius on Aug. 3-4, days ahead the four-year anniversary of contested 2020 elections, for their third annual conference – a platform to report on their work and develop plans to address urgent issues.

This time, however, the consensus seemed elusive.

Opening the conference, exiled Belarusian opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, referring to the recent prisoner exchange between Russia and the West, said that “the very fact of this exchange is an important precedent,” that the Belarusian democratic forces will try to use in future negotiations.

The fate of nearly 1,400 political prisoners has become a divisive topic over the past four years. The once-popular approach of liberating all at once by pressuring Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko with sanctions or, according to the boldest suggestions, toppling his regime by force, has lost many proponents. Instead, the proposal to seize every opportunity to liberate as many prisoners as possible by negotiating with the dictator has gained ground.

Coordination Council member Andrei Yahorau said “the legitimacy of the (Lukashenko) regime in the eyes of the Belarusians is growing,” and that he “would (favor) exchanging the presence of, for example, European ambassadors in Belarus, if (the regime) allows the release of political prisoners en masse.”

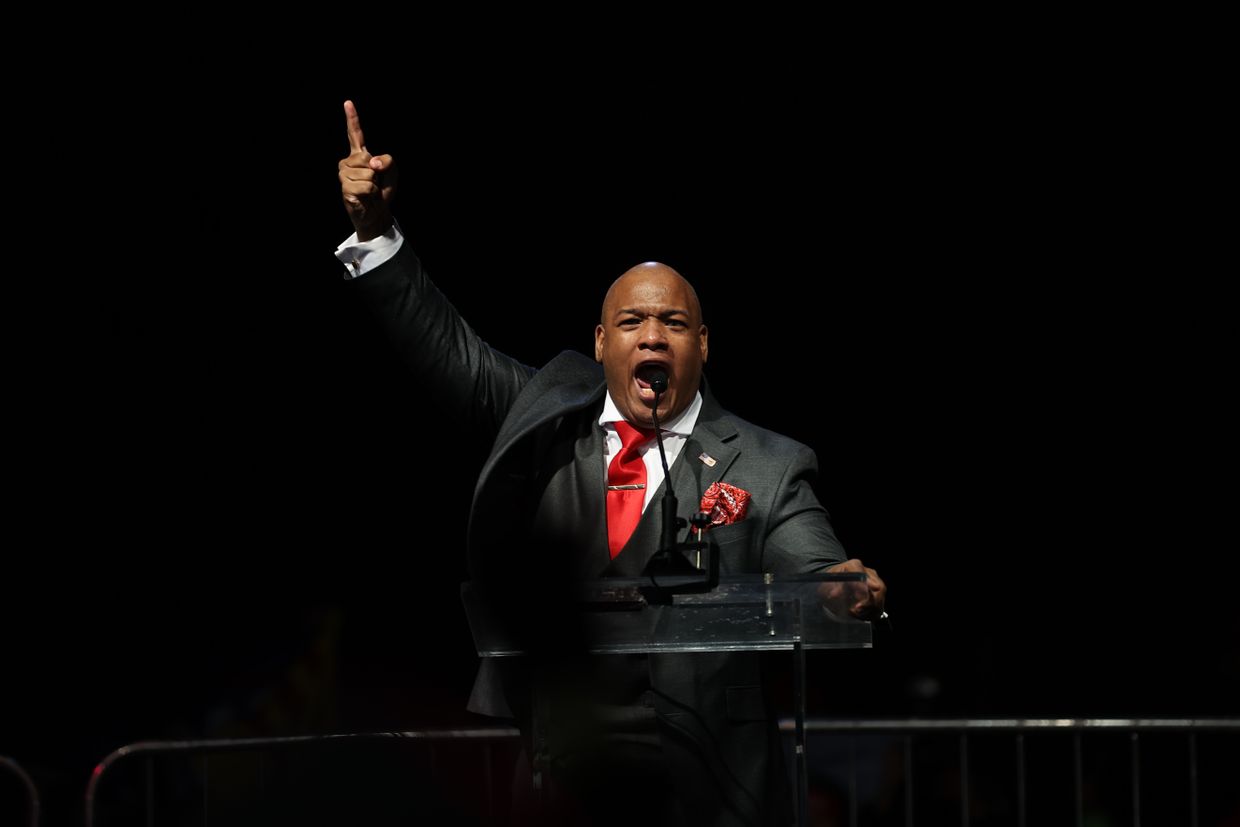

Still, those who reject any negotiations with the dictator are concerned that after releasing some prisoners, Lukashenko would soon capture new ones to maintain leverage. A member of Tsikhanouskaya's shadow cabinet, Pavel Latushka, said he was not ready to recognize the legitimacy of Lukashenko, who “gave orders to kill peaceful Belarusians, who tortures Belarusians in prisons, (and who) destroys our independence.”

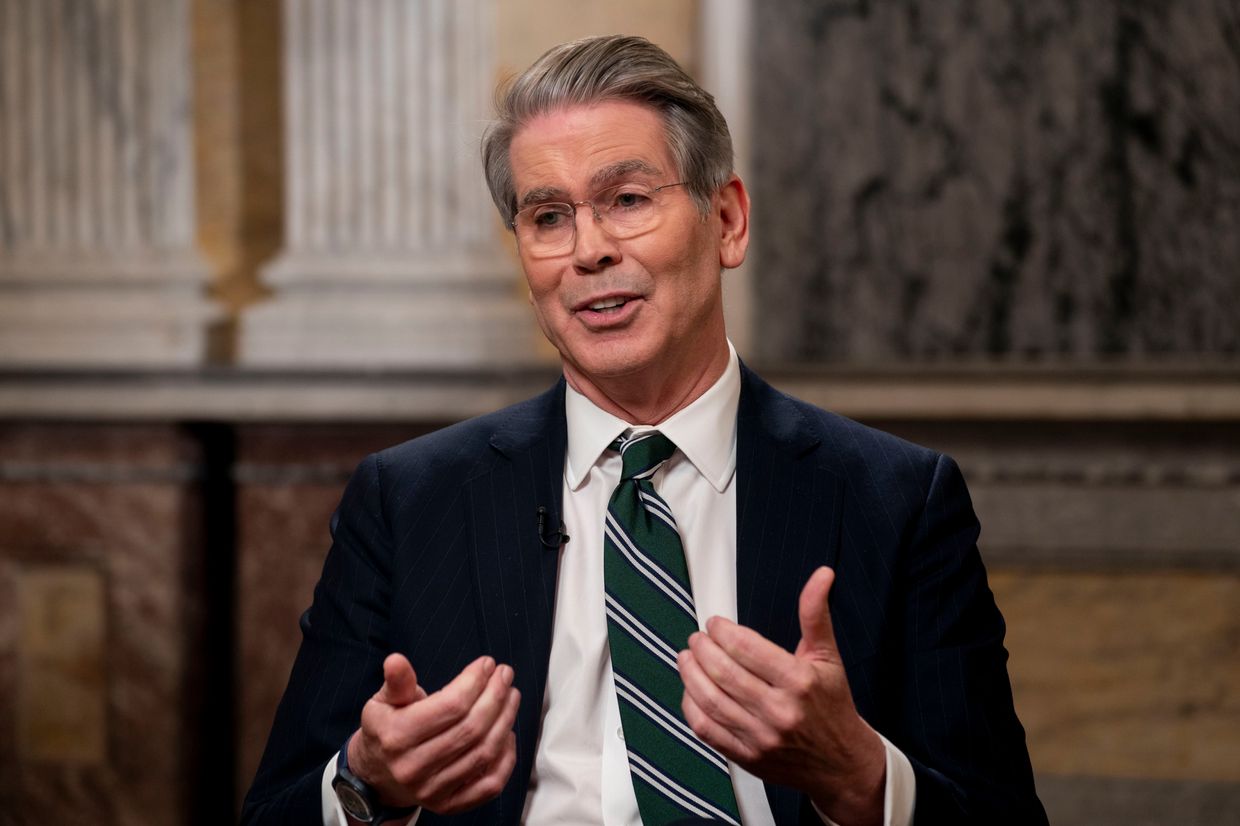

At the conference, Tsikhanouskaya’s Chief Advisor Franak Viachorka and Andrei Stryzhak, the head of the major charity foundation BYSOL, announced the forthcoming launch of the International Fund for Humanitarian Aid to political prisoners.

Initiated by Tsikhanouskaya in January 2024, the charity raises funds on a government level to finance the rehabilitation of former political prisoners and help the families of jailed dissidents.

Preventing an "iron curtain" from falling between Belarusians and Europe was another of the problems discussed at the conference. Despite extensive lobbying by Tsikhanouskaya's team, the European Union’s eighth sanction package included entry bans for Belarusian-registered cars. Lithuania has also revoked residence permits for all Belarusians who have ever been involved with the country’s military, including people who were conscripted, which is obligatory for men in Belarus.

Another difficult issue is the upcoming presidential elections scheduled for 2025 in Belarus. After reportedly beating Lukashenko in the 2020 election, Tsikhanouskaya assumed the role of president-elect, and has claimed to be the legitimate leader of the country. But with new elections approaching, some members of Tsikhanouskaya’s team raised the issue of her status after the vote.

The conference concluded that Tsikhanouskaya would continue as Belarus’ national leader until fair and free elections are held, or if she decides to step down. This was recorded in the Cooperation Protocol, a memorandum between Tsikhanouskaya’s office, her shadow cabinet, and the Coordination Council, which was designed as a proto-parliament but that yet lacks nationwide support. Tsikhanouskaya’s critics within the Belarusian opposition have questioned her lengthy tenure as opposition leader.

Meanwhile, Platform 2025, a declaration signed by a wider pool of opposition actors, states that Lukashenko holds power illegally and, therefore, lacks the legitimacy to hold elections. The Platform tasks its supporters with “de-legitimizing” Lukashenko and his elections diplomatically.

However, the strategy for this remains unknown: The two leading suggestions are a full boycott of the elections or voting against everyone on the ballot.

A study by the People’s Poll, cited by Viachorka, suggests that core opposition supporters don’t have a strong support for either option: 27% support a boycott, 17% are leaning towards voting against all, 11.5% said they favor disrupting the voting, 4% want to take action after the elections, while another 15.7% believe no action should be taken.

Lukashenko’s elections will be neither legal nor fair, Tsikhanouskaya said in her closing remarks to the conference.

“And we will strive for their non-recognition,” she said. “We will develop a common strategy for what to do on the day of the ‘non-elections,’ and before and after them.”