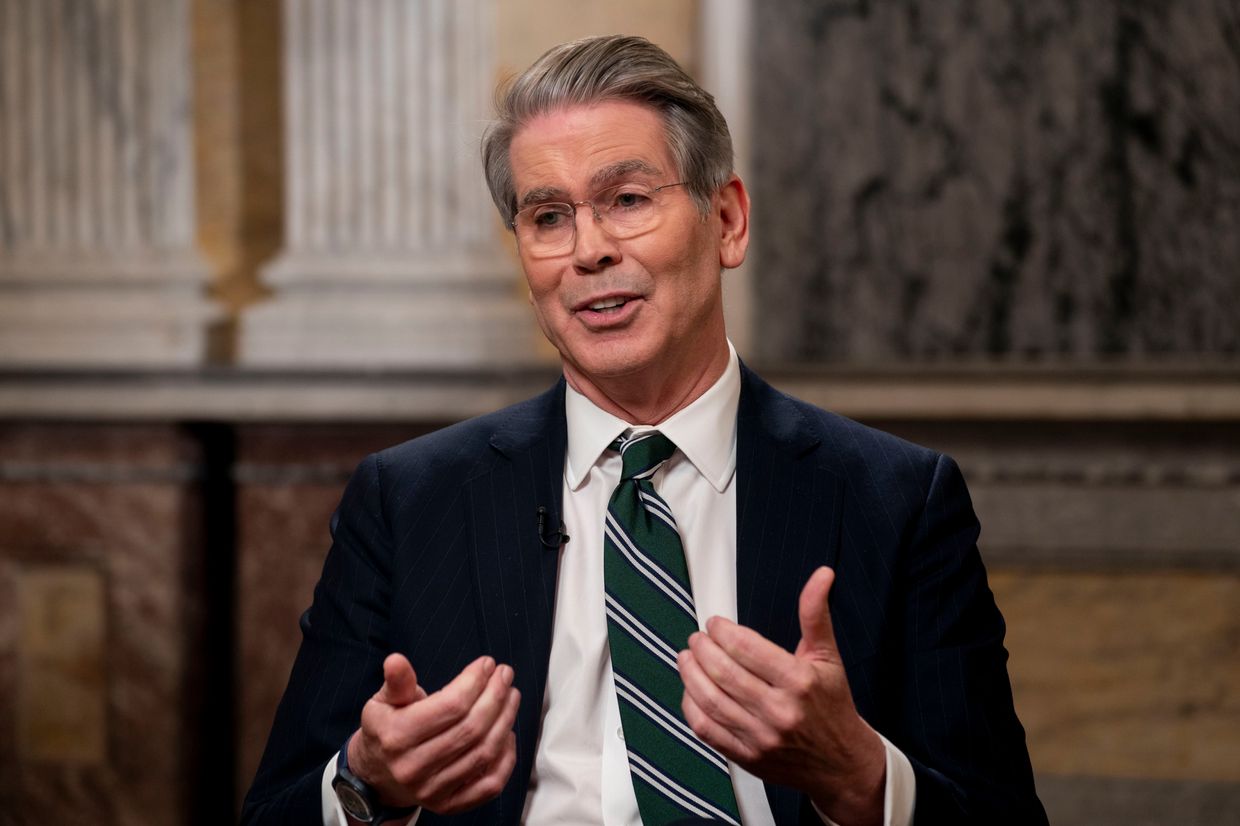

Deputy Defense Minister Dmytro Klimenkov has been given one of the most sensitive jobs of his incoming team: reforming and managing Ukraine’s troubled military procurements. His overloaded daily schedule barely hints at the scope of the issue.

Former Defense Minister Oleksiy Reznikov and his entire team were fired after multiple corruption scandals came to light, mid-war. In 2023, journalists revealed that the ministry was buying food at highly inflated prices and ordering worthless jackets from a Turkish company connected to a Ukrainian lawmaker’s family.

Deputy Defense Minister Vyacheslav Shapovalov and the ministry’s procurement department head, Bohdan Khmelnytskyi were charged with embezzlement, causing over Hr 1 billion ($27 million) in losses, according to Ukraine’s Security Service.

Another procurement official, Oleksandr Liyev, is in custody, and police are investigating his successor, Toomas Nakhkur. Each faces up to 12 years in prison. They were supposed to procure 100,000 mortar shells by February 2023, but none ever materialized.

This alleged Hr 1.5 billion ($39.6 million) scheme coincided with a severe ammo shortage at the peak of the battle of Bakhmut.

Klimenkov, who took office in November, faces an uphill battle.

He was hired to fundamentally transform Ukraine’s troubled defense acquisitions into a robust, efficient system, with impeccable oversight. This means tearing any traces of Soviet influence out with the roots.

“The priority of our work is to finish the reforms started decades ago — defeating the Soviet legacy,” Klimenkov said, popping into a ministry conference room for a chat with the Kyiv Independent.

“We eliminated it from the street signs and monuments but it lives on inside the very system.”

The snag is that Ukraine is also fighting a total war for survival. So Klimenkov’s team also has to ensure that the supplies keep flowing with no interruptions. The reforms have to be done as quickly as possible, but also be smooth and gradual enough to prevent dangerous disruptions to procurement.

Some steps were made. The scandal-ridden department was disbanded. In its place, the ministry created two agencies which have the sole authority to buy things for the military — one vehicles and weapons, the other everything else.

The ministry itself provides policy, oversight and a list of what everybody needs. This is only the beginning of Klimenkov’s responsibility.

“The management, the logistics, they have many constituent parts that have to be tracked daily. The better we see these important things, the faster we can react to problems and there are plenty of problems because we’re at war,” he said. “Creating the two agencies is just the tip of the iceberg.”

Clad in black business casual, Klimenkov carries himself with a civilian vibe.

He has this in common with much of the team picked by new Defense Minister Rustem Umerov — they tend to be younger, with backgrounds in business, civil society or digital innovation.

While some of them have done a lot of work to support the military, they hadn’t been part of it. Umerov himself previously headed the State Property Fund for about a year. Klimenkov was his first deputy.

Before that, Klimenkov worked in the private sector. He took his engineering and business management degrees to Ericsson where he last worked as project manager. He then went to Ukraine International Airlines, serving as the air fleet logistics director and then as director of infrastructure and logistics.

The deputy minister said he brought that experience into his current job. The first thing he did was run a cross check to see where the problems were.

“The first problem I saw is that procurements were concentrated in certain power verticals,” he said. “This is unacceptable in business big or small, because the problem is corruption arising from conflict of interest. The ministry wrote its own technical standards for what to buy, then did the purchases themselves.”

The replacement model was worked out based on what top NATO countries do, modified for Ukraine’s situation. Ordinarily, there might be one procurement agency, like what Ukraine did for health acquisitions with Medical Procurements of Ukraine.

But since Ukraine is at war and weapon purchases require extra layers of military secrecy, the defense ministry made two procurement agencies — lethal and non-lethal.

The non-lethal agency will do all its procurements through Prozorro, an online procurement system, and is being run by Arsen Zhumadilov, who formerly headed up Medical Procurements of Ukraine. The ministry is working with the Anti-Corruption Council and civil society for extra oversight.

Lethal purchases won’t be open to the public, but can be viewed by enforcement bodies and the countries making and providing the weapons.

Klimenkov also said that they’re eliminating the lack of international cooperation that occasionally disrupted delivery contracts.

“Every week I meet with U.S., U.K., European allies, where we coordinate our action plans and show we’re doing this or that or what we need by this time.” This avoids wasting time and forestalls any artificial changes to market competition that might cause prices to spike.

There will also be a feedback system for weapon systems, which will be battlefield tested and referred back to the developer for improvement if there are issues.

“We are not allowed to make mistakes,” Klimenkov said. “We can’t stop for 2-3 months to fix something.”

As for the new policy department, it will establish all the rules, control for quality and ensure that it’s not possible for a supplier to pull another fast one.

Klimenkov broke the food scandal down like this: the ministry has a list of all provisions it needs to buy. Unscrupulous suppliers saw the opportunity to manipulate prices. Goods that they supplied rarely and in small quantities got deeply discounted. But prices were doubled or tripled on goods that they supplied often, in large quantities.

This was enough to disguise the profiteering for a while, with the participation of allegedly complicit defense ministry officials.

There are now multiple ongoing court cases involving suppliers. The ministry is working to claw back some of the money these suppliers have been paid, or their assets.

The new defense team is trying to curb price tampering by introducing price floors and ceilings on goods. They also dissolved the previous procurement-handling offices within the ministry.

The newly-created bodies will have to be better-managed. Short-term KPIs have already been set and the ministry has signed statutes making independent supervisory boards mandatory at both, Klimenkov said. To attract qualified people, the positions have to offer competitive market rates.

“Unfortunately, ministries tend to give people low salaries and high responsibilities. It doesn’t work like that,” Klimenkov said. “People have to know their career will develop and be motivated.”

As for himself, the deputy minister has one master KPI in mind above all others.

“My KPI is for my job to become unnecessary,” he said.