Warning: This article contains graphic photos and descriptions of graphic scenes.

A decomposed human hand with the remains of flesh, bleak and brown save for one splash of color — two thin blue-yellow rubber bracelets. The colors of the Ukrainian national flag.

The hand was from a body of the hundreds of victims of Russian troops, soldiers, and civilians, exhumed from a mass burial site near the then-just-liberated Izium, a city in Kharkiv Oblast, in September 2022. Captured by journalists, the photo spread worldwide and became a symbol of Russian violence and Ukrainian resistance.

Many assumed that the man, soon identified as a Ukrainian soldier Serhii Sova, was killed in battle. Only one person knew that the truth was more grim.

Months earlier, Sova’s widow saw the photos of her dead husband on Russian Telegram channels. The photos showed he had been shot in the head, his hands tied behind his back. All signs pointed to the fact that he had been executed while in Russian captivity. Still, when his body was found near Izium, it hit her again.

“My heart and everything inside me sank,” Oksana Sova says, recalling the moment she saw the photos in the media and recognized the bracelet and tattoos on her husband’s body.

This story is one vivid example of a recently increasing number of public reports of executions of Ukrainian soldiers by Russian forces. According to Ukraine’s Prosecutor General's Office, cases of executions of Ukraine’s soldiers began to surge in 2023.

Videos and photos of brutal executions have been appearing online more frequently since the spring of 2023. In March 2023, a video was published on Telegram showing Russian soldiers shooting a captive Ukrainian soldier after he said "Glory to Ukraine." Only a month later, a different video showed Russian soldiers cutting off the head of a Ukrainian soldier as he screamed in pain. At the end of the video, a Russian soldier holds up the severed head.

Cases like this continue to surface in 2024, often accompanied by horrendous videos. Some of them feature decapitation and mutilation of bodies.

Prisoners of war (POW) are granted protection under international humanitarian law, namely the 4th Hague Convention on the Laws and Customs of War adopted in 1907. According to the convention, killing a POW constitutes a war crime, and a soldier is considered a POW and cannot be attacked from the moment he lays down his weapon or no longer possesses the means of protection, voluntarily surrenders, or demonstrates such an intention. This also applies to those who find themselves under the power of the enemy, rendered defenseless by unconsciousness, injury, or illness.

It’s impossible to know how many Ukrainian soldiers have been executed after being taken captive. Recording and investigating such crimes is extremely difficult due to limited access. Since the start of the full-scale invasion in 2022, the United Nations has documented the execution of 42 Ukrainian service members. Ukraine has documented 102 such executions as of October 2022. The actual figure could be much higher.

Even for the cases that have been recorded, justice appears to be a doubtful prospect. Russia doesn’t recognize or investigate POW execution cases. In Ukraine, the Prosecutor General’s Office has opened 27 investigations into the killing of POWs. So far, only three cases have made it to court, only one of which is being considered in the presence of a Russian soldier and two in absentia. No verdicts have been made yet.

The Kyiv Independent has collected testimonies about three executions of Ukrainian soldiers by Russian troops. We received photo evidence of the crimes, which the Russian soldiers themselves distributed on Telegram channels shortly after the execution, a unique video shot from a drone by Ukrainian military officers, and spoke with an eyewitness to an execution who was captured, survived abuse in captivity, and returned to Ukraine. These are their stories.

‘He’s better off this way’

On June 1, 2022, in Donetsk Oblast, near the village of Yarova, at dawn, Russian artillery fired intensely in preparation for an assault on Ukrainian positions. Next, the tanks rolled in.

Roman Zarudny, callsign “Irishman,” a soldier from the National Guard of Ukraine, was at the outpost that was among the first to be attacked. A 32-year-old former circus artist who voluntarily joined the military at the beginning of the full-scale invasion, he had been fighting for less than three months at the time of the assault.

As he remembers the attacks, Ukrainian soldiers didn’t stand a chance.

"We should have pulled back because we had nothing to fight with,” he recalls. “I managed to fire one magazine, then there was smoke, a grenade, a bang — and that was the end of my war."

Zarudny was in the dugout with two other infantrymen. One told his comrades he was wounded.

"He said, 'Guys, I think I’m 300’,” he recalled his comrade saying, using the military code for “wounded.” “We checked, cut off his clothes, and saw his knee and elbow were shot."

The Russian fire subsided as their infantry fighting vehicles moved deeper into the village. The soldiers removed the wounded soldier's body armor, bandaged him, and considered their next move. It was too late to retreat.

"I had already said goodbye to life at that point," said Zarudny.

The Russian troops were approaching the dugout. Zarudny said he didn’t want to get captured and recalled one of his comrades echoing him.

Zarudny took a hand grenade.

“I thought — if they get in, I could take a few of them with me,” recalled Zarudny.

But after a brief discussion, they decided to surrender. Zarudny recalls that a Russian soldier saw the grenade in his hand, warned him not to use it, and took it away.

Then, the Russian soldiers noticed the wounded soldier.

"A Russian soldier looked at him, cocked his Kalashnikov, and fired two shots at him,” Zarudny recalled. “Then, he said: 'Don't take it the wrong way. His legs were shattered. I did it so he wouldn't suffer. He’s better off this way’."

The Russian soldiers took the other two soldiers as prisoners. Zarudny was released in a prisoner exchange a year and a half later, in January 2024. The second soldier is still officially listed as a prisoner. As for the third one, he is formally listed as missing.

What happened to his body is unknown, and his family is still searching for him, hoping for the best. Soldiers from the Kulchytsky Battalion, who fought alongside Zarudny’s brigade on June 1, 2022, confirmed the dramatic turn of events that day, unfavorable for Ukrainian forces.

‘It was an execution’

It is one of the most widely recognized photos of Russia’s invasion.

In September 2022, after the liberation of Kharkiv Oblast, a large burial site was found in the forest near the city of Izium — the bodies of Ukrainian soldiers and civilians, killed by Russians. Soon after, Ukrainian authorities began their exhumation.

One of the bodies exhumed drew the attention of the media on site: Its half-decomposed wrist carried a rubber bracelet in the colors of the Ukrainian national flag. The photo flew around the world.

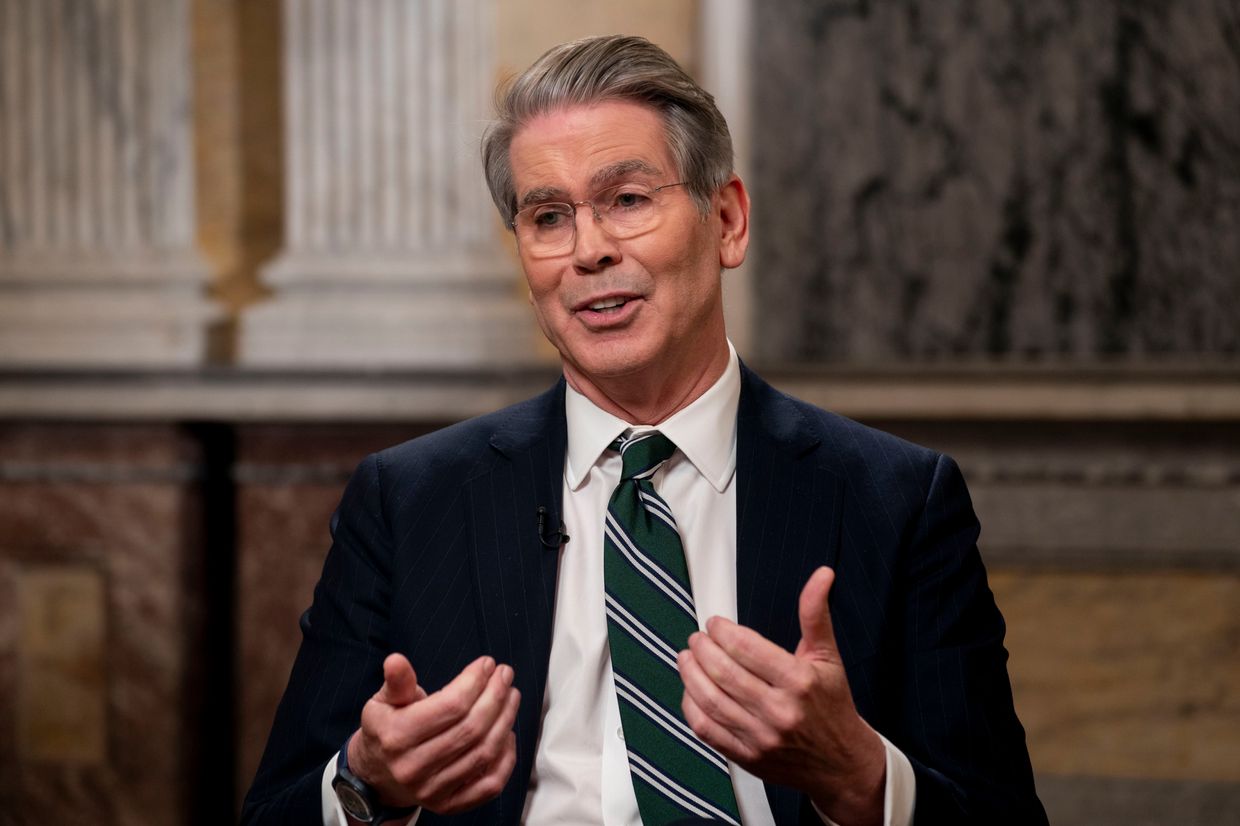

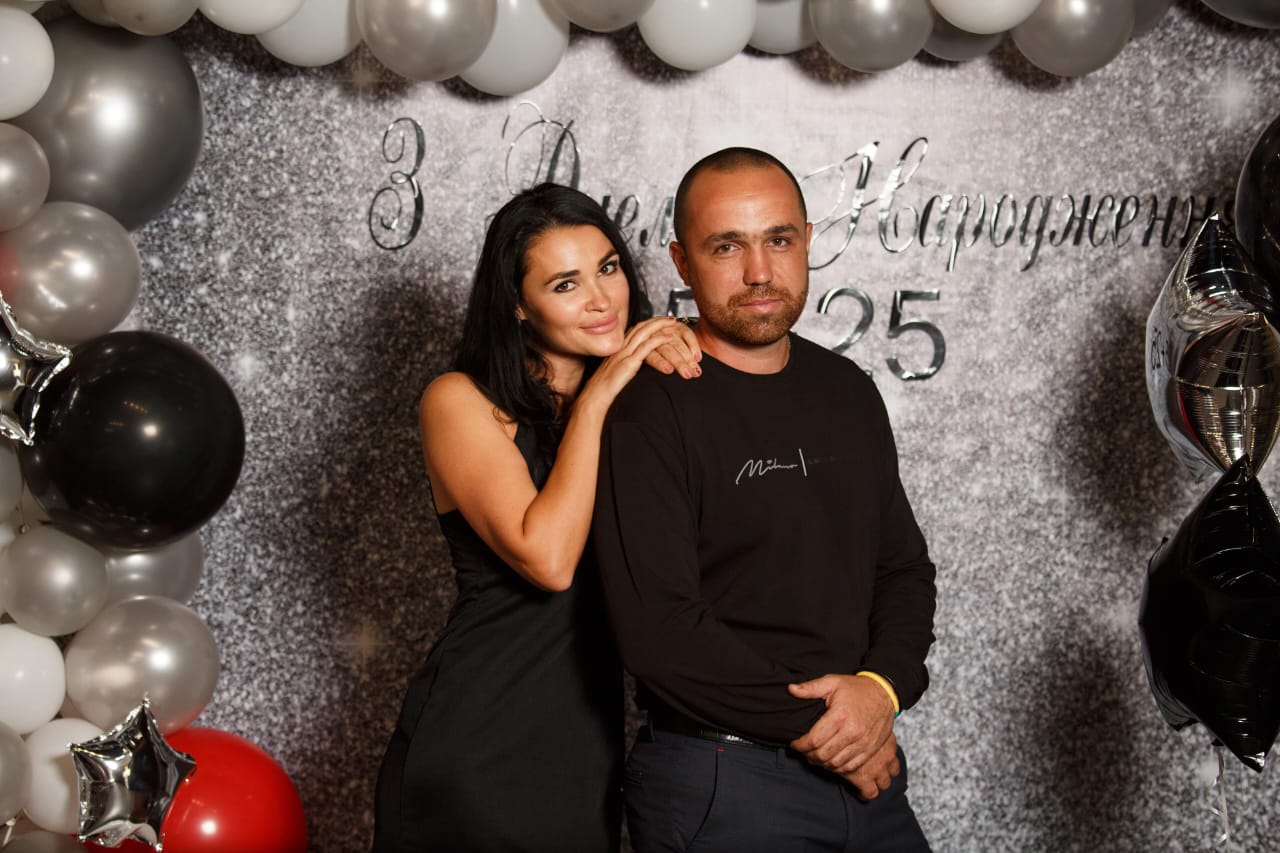

Oksana Sova from Nikopol, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast, recognized her husband, 35-year-old serviceman Serhii Sova, in the photographs.

By that time, he had been officially listed as missing for almost five months, since April 19, 2022.

When the body was found in September, Oksana already knew her husband was dead.

Oksana has never shared the story of how she found out what happened to her husband until now. Nor has she discussed what she experienced in the days since she learned that he had gone missing.

"Every single day, I was checking Russian Telegram channels, looking for prisoners, the dead, everyone,” she recalls. “After a month, in May, I found what I was looking for.”

Scrolling through Telegram channels, Oksana came upon familiar features. In the photo, her husband was stripped down to the waist, his hands tied behind his back. In the back of his head, a gaping gunshot wound.

The nature of the photo, the absence of clothes, the tied hands — all pointed to the fact that Russian soldiers had killed Serhii when he was already captured and should have been protected as a POW.

“It was a photo taken after his execution,” Oksana says.

“In the photo, he was very thin — my husband was never that thin. I kept looking... It was tough in the first days. I noticed that these bastards had taken everything. There were no silver chains with the pendants I had given him, no belt, no boots."

There could be no mistake in identifying him: The photo showed the soldier's face and recognizable tattoos on his torso — an owl, a samurai, and a sakura. Near Serhii was at least one more dead man, his hands tied behind his back and a t-shirt pulled over his head.

The photographs documenting this war crime were later deleted from the Russian Telegram channels, which they had posted along with other photos of captured and executed Ukrainian soldiers with a call urging Ukrainians to surrender in order to survive. Oksana also later deleted the photos from her phone, fearing that her two children would accidentally find them. However, friends of Serhii saved screenshots of the posts and shared them with the Kyiv Independent.

The circumstances of the battle during which Serhii was captured are recounted by his comrades, who managed to retreat in time. In April 2022, the 3rd Company of the 1st Battalion of the 93rd Brigade was holding positions in tree lines near the villages of Sulyhivka, Dibrivne, and Nova Dmytrivka in the Izium district of Kharkiv Oblast. This location is about 50 kilometers from where Serhii’s body would be found in September.

"We held the defense there for about two weeks and tried to break through. On April 19, at 2 a.m., we received the order to retreat because we were being encircled. We moved back to another tree line,” recalls Yurii, callsign "Pavuk," who was at that time a squad commander of the 3rd Company, 3rd Platoon, 1st Battalion of the 93rd Brigade.

He remembers how the company was repositioning from 2 a.m. to 6 a.m., when Russian troops saw it and brazenly advanced. Artillery was hitting them from all sides, causing them to scatter before the enemy tanks arrived. Serhii’s position was about 100 meters from Yurii, closer to the road.

“The Russians drove in there with tanks and armored personnel carriers and started destroying everything in sight,” he says, adding that he knows of only two men who were taken captive that day. “Everyone else who was there died. There were about 40 people. This all happened in about four hours."

Thanks to photographic evidence, which the Russians published on Telegram channels, it became clear that Serhii survived that heavy battle and even remained unharmed, but was executed by Russian soldiers. According to the Kyiv Independent’s sources in Serhii’s unit, the 93rd Brigade, the Russian troops that were stationed in the area were from the 4th Tank Kantemirovskaya Division.

For Oksana, establishing the truth about what really happened to her loved one and remembering him in a dignified way is vital. Oksana and Serhii had been together for 17 years. They ran a dog training business together. He was a boxer and had served in the Ukrainian army before. He left behind two children: a son, Marat, now 16, and a daughter, Elina, who is 11.

"Seventeen years of our life together. These were the best years of my life, and I am very grateful he was my husband. He loved us very much; we were everything to him, and he spent all his free time with the family."

Many testimonies of executions of prisoners on the battlefield in this war have been captured by aerial footage. The Kyiv Independent obtained a video, according to our sources inside the brigade, dated Feb. 18, 2024, shot in the trenches between the villages of Robotyne and Verbove in Zaporizhzhia Oblast. It shows two unarmed soldiers of the 82nd Separate Air Assault Brigade walking near the trenches before being shot by an automatic firearm moments later.

"During the battle, the Russians killed two of our guys. Two more survived. When the Russians entered, our guys raised their hands, but the Russians killed them," said one of the eyewitnesses who saw what happened that day during a live broadcast from a drone.

Spreading fear

Executions on a battlefield remain among the least documented deaths in war. This crime extremely rarely leaves witnesses. Units of such cases fall into the lenses of drones or are recorded by the killers.

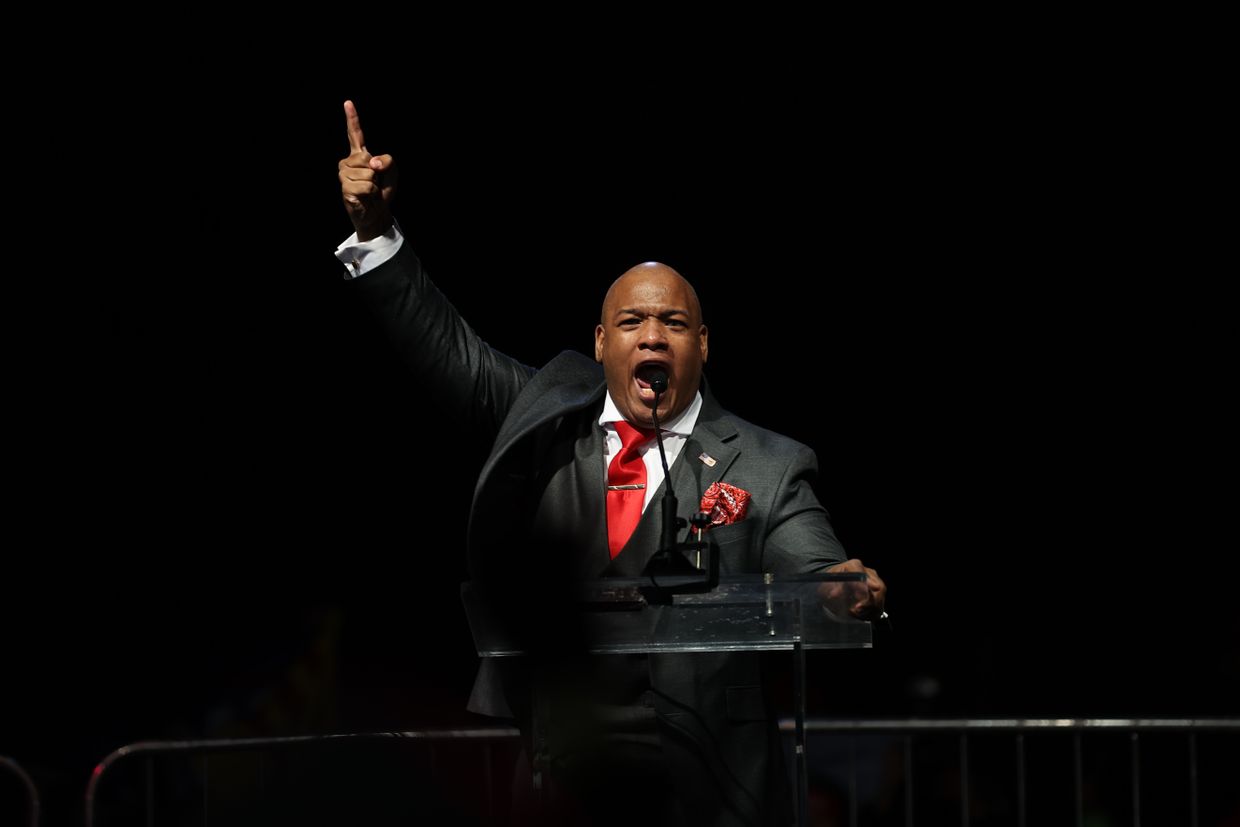

"This has been practiced in the Russian army since the (Second) Chechen War. And they did it very much in many conflicts in which they participated. I think that this is a specially organized practice, and it is aimed at two aspects," says Volodymyr Yavorskyi, program director of the Ukrainian Nobel Prize-winning Center for Civil Liberties. He believes that it’s all about spreading fear: firstly among people already on the front lines that they will most certainly die, so they should retreat. Secondly, among those who are expected to be mobilized. "A person sees this and thinks that mobilization is inevitable death,” he said.

As practice shows, taking or not taking a prisoner in battle depends on various factors, said a 47-year-old major of Ukraine’s Armed Forces, who we identify only by his callsign "Karay" because he has no official permission to comment on the issue. “Karay” has witnessed many acts of cruelty during his 10-year service in the war in Ukraine in various brigades.

"Prisoners can be executed because of the desire to take revenge for fellow servants, or when a group cannot or does not want to spend time on guarding and evacuating prisoners, so they kill them.” At the same time, the higher the status of the unit, like Russian marines or paratroopers, the higher the probability that the prisoners will remain alive, “Karay” said. “There is a higher percentage of professional soldiers. For them, war is work, and they avoid emotions.”

On the other hand, there are some Russian units, such as the “Rusich” Sabotage-Assault Reconnaissance Group,” which publicly declares that they do not take prisoners. They were the ones who published the video featuring the cutting off of the head of a Ukrainian soldier.

"In some units, according to radio intercepts, Russian commanders practice involving their soldiers in executions, including with demonstrative brutality, to bind the "team" with blood and crimes so that the soldiers will fight to the last and not surrender to the Ukrainians,” “Karay” said.