Unity Day, observed on Jan. 22 in Ukraine as a state holiday, typically commemorates the 1919 unification of eastern and western Ukraine. But this year, the date garnered attention for a decree signed by President Volodymyr Zelensky relating to modern-day Russian territories that were historically populated by Ukrainians.

The decree titled "On the Territories of the Russian Federation Historically Inhabited by Ukrainians" outlines a directive for the Ukrainian government to collaborate with experts and develop a plan aimed at researching, publicizing, and safeguarding the cultural identities of Ukrainians who have lived in the borders of modern-day Russia’s Krasnodar Krai, Belgorod, Bryansk, Voronezh, Kursk, Rostov regions that border Ukraine.

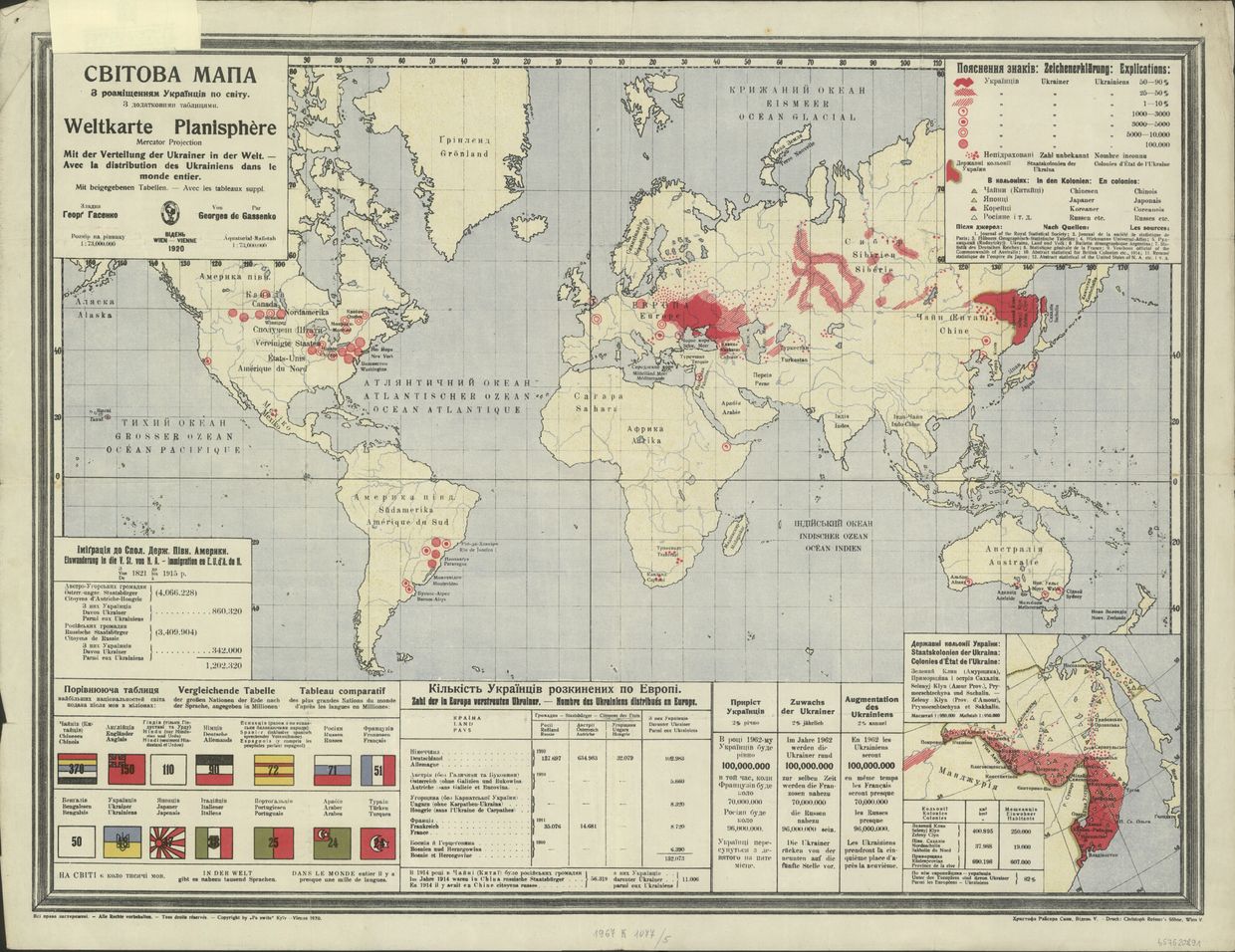

“It’s important to know that ethnic Ukrainians are represented in almost every corner of the world, even in the territories of the aggressor state,” Vladyslav Havrylov, historian and researcher with the Where Are Our People Project, told the Kyiv Independent.

“There is a need for systematic awareness efforts striving to establish communication and urge these individuals to actively resist Russian aggression and advocate for Ukraine on international platforms, if only out of respect for their historical roots.”

The decree doesn't make any territorial claims to these regions, unlike Russian dictator Vladimir Putin’s frequent ahistorical assertions about Ukraine, such as that it was an “invention” of the Bolsheviks and therefore not truly sovereign.

While supporters see the decree as a politically savvy move to foster a better global understanding of Russia's long-standing crimes against Ukrainians and other groups who have lived under Russian rule, some historians caution that it needs to be less ambiguous in order to have any relevance.

It has also left some individuals originally from those Russian regions who moved to Ukraine wondering if they’ll see their dreams realized and someday obtain Ukrainian citizenship.

‘What do you mean, Russian? We’re Cossacks.’

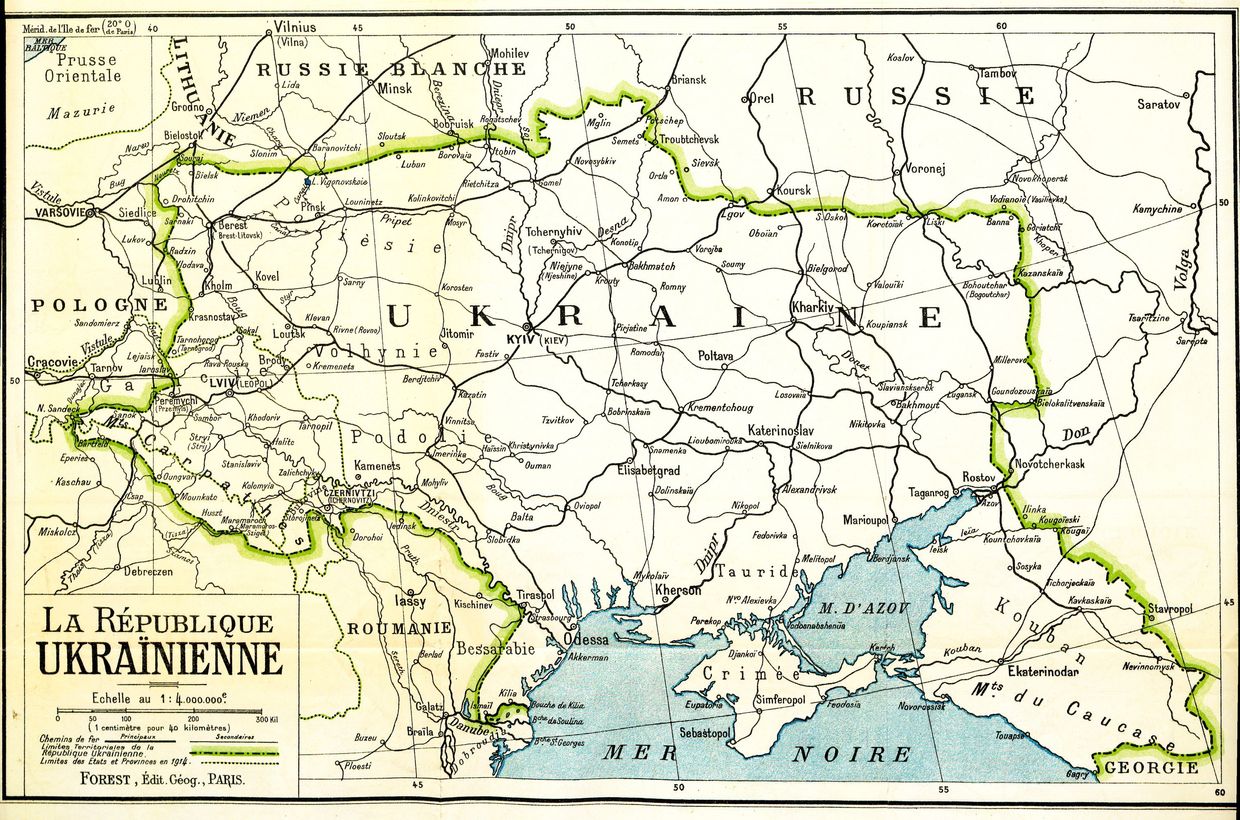

Ukraine's territory, according to the 1991 borders, covers 603,700 square kilometers (375,000 square miles), but in 1918, during Ukraine's national liberation struggle, the Ukrainian State under Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky covered an area larger than 800,000 square kilometers (497,000 square miles).

This included cities like Belgorod, part of modern-day Russia, which now serve as launch points for Russian missiles and drones targeting Ukrainian cities and killing civilians.

Deportations — including to Russia’s Far East — mass repressions orchestrated by the Soviet authorities, famine, and a number of other repressive measures in the 1920s and 30s would go on to deal significant blows to the Ukrainian communities who lived in those regions.

Ukrainians didn’t make up the entire local population of these regions. In certain instances, they were resettled after Russian authorities displaced indigenous groups who lived there. What happened to them reflects a larger state policy of forced assimilation backed by Russia.

Zelensky’s presidential decree mentions the historical regions of Kuban, Starodubshchyna, and northern and eastern Slobozhanshchyna, a passing acknowledgment of the historical complexity tied to this decree.

Slobozhanshchyna, also known as Sloboda Ukraine, encompasses parts of modern-day Sumy, Kharkiv, and Luhansk oblasts but also parts of Russia’s Belgorod, Kursk, and Voronezh oblasts. Russia’s Krasnodar Krai includes most of the historical Kuban region, while Starodubshchyna is primarily situated in Bryansk Oblast.

The work of historians over the years has already revealed that some of the Ukrainians who lived in those regions harbored concerns about being considered part of Russia.

In his 2008 book “Ethnic Boundaries and the State Border of Ukraine,” for example, historian Volodymyr Serhiychuk cites an open letter dating back to 1925 from residents of the settlement of Zaoleshenka in Kursk Oblast, located less than 10 kilometers from the modern-day Ukrainian border.

The residents of Zaoleshenka convey their wish to Soviet authorities to formally be part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, arguing that more than 5,000 residents of the settlement identified as "100% ethnic Ukrainians," and their economic ties were closely linked to the Ukrainian cities of Kharkiv and Sumy.

“We dare to state that a categorical rejection of our petition and general silence on the issue in question, or simply imposing one’s own considerations from above in the sense of establishing borders without the consent of the interested population of the given area, will have a harmful and distrustful impact on the prestige and trust of the population of the central Soviet authorities, violating the right to self-determination,” the letter ends.

Another letter from 1924 cited by Serhiychuk in his work reveals Ukrainians' discontent about Shakhty and Taganrog, cities in modern-day Rostov Oblast, becoming part of Russia. The letter highlighted that most people in these areas were Ukrainians and argued that it would make more sense for these lands to belong to the Ukrainian SSR.

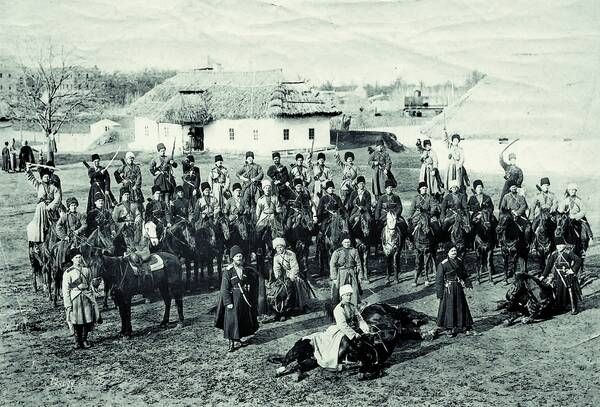

One of the most famous examples of Ukrainians who lived in the territory of modern-day Russia is connected to the historical Kuban region, modern-day Krasnodar Krai, where different groups of Ukrainian Cossacks were forcibly resettled in the 18th century.

“The Kuban Cossacks communicated in the Ukrainian language and identified themselves as Ukrainians. According to the census conducted in Tsarist Russia in 1897, the Kuban region was home to over 900,000 Ukrainians, constituting 47.4% of the population. They were the largest ethnic group in the region,” Havrylov explained.

Ukrainian documentary filmmaker Valentyn Sperkach recorded interviews with elderly locals from a village in Krasnodar Krai descended from those Cossacks for his 1992 film “Kuban Cossacks: And Already Two Hundred Years…”

The documentary subjects recount family memories of forced deportations in the 1920s and 30s to destinations as far off as Kazakhstan and the most able-bodied looking people being targeted by authorities and shot dead. When a village was left half empty, people from other parts of Russia — such as Leningrad Oblast, which is over 2,000 kilometers away — were resettled there.

The children of those who were not deported or killed were told in schools that there was no such nationality as “Cossack” and that they were Russian.

The hints of the Ukrainian language in the documentary subject’s voices – such as the use of a soft “g” instead of the hard Russian pronunciation – coupled with poignant family testimonies, serve as examples of how Russian aggression blurred the lines of cultural identity in Krasnodar Krai.

When two women are asked if they identify as Russians or Ukrainians, one responds: “I don’t know. Papa was Russian, we’re Russian.”

“What do you mean, Russian?” the other woman counters. “We’re Cossacks.”

“Cossacks, yes. They tormented us for that.”

Asked why it states in his passport that he’s Russian and not Ukrainian, one man replies: “I had a friend, his surname was Zhovtobriukh, but it was spelled Zhovtobriukhov. (This was) to hide the fact that our surnames were Ukrainian. Because they strangled us, God have mercy! Because they made all of Krasnodar Krai Russian.”

Another man tells the camera that they “used to be” Ukrainians. However, he doesn’t go as far as to call himself Russian. He is questioned about locals’ cultural identity, to which he responds, "We don't even know who we are now."

When pressed for a more definitive answer, he chuckles and proclaims, "Werewolves!"

‘I’m a Ukrainian without Ukrainian citizenship’

One of the initial main concerns raised by the decree is the lack of clarity in some of the terms used, Kyrylo Halushko, a historian and ethno-sociologist who has researched interethnic relations in the post-Soviet space, told the Kyiv Independent.

“In the context of international law — and this decree concerns another state, thus having an international context — such matters are crucial,” he added.

There is no dispute that Russia has long been trying to undermine Ukrainian national identity. However, certain historical ethics and expert assessments are needed going forward to establish clearer definitions of terms like “historically inhabited lands,” according to Halushko.

Being precise and careful with such wording also helps to make sure that it cannot be applied against Ukrainian territory at any point in the future, he added, citing Hungary’s claims over Transcarpathia and the ethnic Hungarians who live there as an example.

The decree does not explicitly acknowledge the previous history of the groups who lived in some of these regions before Ukrainians were settled there.

It also does not mention the significant number of Ukrainians living in far-off regions of Russia. For example, the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug–Yugra in Siberia is home to over 40,000 Ukrainians according to Russia’s census in 2021.

“How ‘historical’ are we there? How many generations are needed? Perhaps these territories are already more ‘ethnically Ukrainian’ than some mentioned in the decree, which have long been completely assimilated by Russian and Soviet imperial practices,” Halushko added.

While Halushko criticized certain aspects of the decree, he acknowledged that the authors and timeframe for its implementation remain unknown and that these initial oversights could be rectified in the future.

The Kyiv Independent reached out to Zelensky’s office for comment but hasn’t gotten a response as of publication time.

Another factor not addressed in the presidential decree is the individuals born in the Russian regions bordering Ukraine who have chosen to embrace their Ukrainian roots and dream of someday obtaining Ukrainian citizenship.

As long as Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine continues, that outcome remains uncertain.

“I’m a Ukrainian without Ukrainian citizenship,” singer Yulia Yurina declared in a post on her social media shortly after Zelensky’s decree was published. “It so happened that I was born in the aggressor country.”

Yurina, whose music blends Ukrainian folk traditions with contemporary music styles, is originally from the town of Anapa in Russia's Krasnodar Krai. But thanks to the efforts of local residents who preserved Ukrainian traditions across generations, she was shaped by Ukrainian culture from an early age.

“There were Ukrainian-speaking families, Ukrainian schools, and Ukrainian newspapers. My friend's family lived on Shevchenko Street, and they spoke Ukrainian at home,” Yurina told the Kyiv Independent.

After Russia illegally annexed the Crimean Peninsula and invaded Ukraine’s Donetsk and Luhansk regions in 2014, there was more pressure put on Ukrainian cultural initiatives within Russian territory. According to Yurina, her own collection of Ukrainian-language materials was even destroyed.

One of Yurina’s acquaintances who works as a teacher was also given a directive “from above” to remove Ukrainian songs from the school repertoire and sing “Russian folk songs” instead.

“It was very strange for the Kuban region where Ukrainian culture prevailed,” Yurina said.

The singer has been living officially in Ukraine since 2012. She initially obtained a temporary residence permit through her university studies in Kyiv. In 2015, she married a Ukrainian citizen.

Despite obtaining permanent residency in 2018, scoring high on the Ukrainian language exam, and actively volunteering for Ukraine since the onset of the full-scale invasion, her citizenship application has remained unresolved for the past year.

After she made a passionate post on social media about her predicament, “hundreds of people” wrote Yurina, sharing similar stories, she said. They expressed how they’d also been living in Ukraine for years but were still hoping to become Ukrainian citizens.

“I understand why it's difficult for people with a passport from the aggressor country, especially during wartime when the country is worried about security, to become citizens,” she said.

“But it turns out to be a pressing issue affecting the fate of many people. Hopefully, a solution will be found that satisfies both sides, is safe, less complicated, and helps determine the destinies of many people whose home is Ukraine.”

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan, sharing an important culture-related story from Ukraine. Due to Russia’s ongoing genocide, most stories about Ukrainian culture will, unfortunately, be related to war for years to come. But Ukrainian culture is finding ways to persevere and it's important to share these stories.

If you liked reading this article, please consider continuing to support our reporting to see more like this.