Editor's Note: This is episode 3 of "Ukraine's True History," a video and story series by the Kyiv Independent. The series is funded by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting within the program “Ukraine Forward: Amplifying Analysis.” The program is financed by the MATRA Programme of the Embassy of the Netherlands in Ukraine. Subscribe to the series' newsletter here.

Russia has not only killed tens of thousands of Ukrainians and ruined much of the country's infrastructure since the start of the full-scale invasion.

It has also aimed at destroying the core of Ukrainian identity — language, and culture — in the territories it has occupied.

Businesses and institutions there were have been forced to switch to Russian, while the Russian curriculum has been imposed in schools.

The Kherson Fine Arts Museum and the Arkhip Kuindzhi Museum in Mariupol, among others, were emptied of their priceless cultural assets during Russian occupation.

Ukraine's Culture Ministry said Russia has committed over 1,271 crimes against Ukraine's cultural heritage since it scaled up its assault against Ukraine in February 2022. As many as 473 cultural sights, including historical churches and theaters, have been destroyed by Russia's shelling and missile strikes over the year of the all-out war, according to the ministry.

But Russia's attempts to destroy the Ukrainian language and culture did not start in 2022.

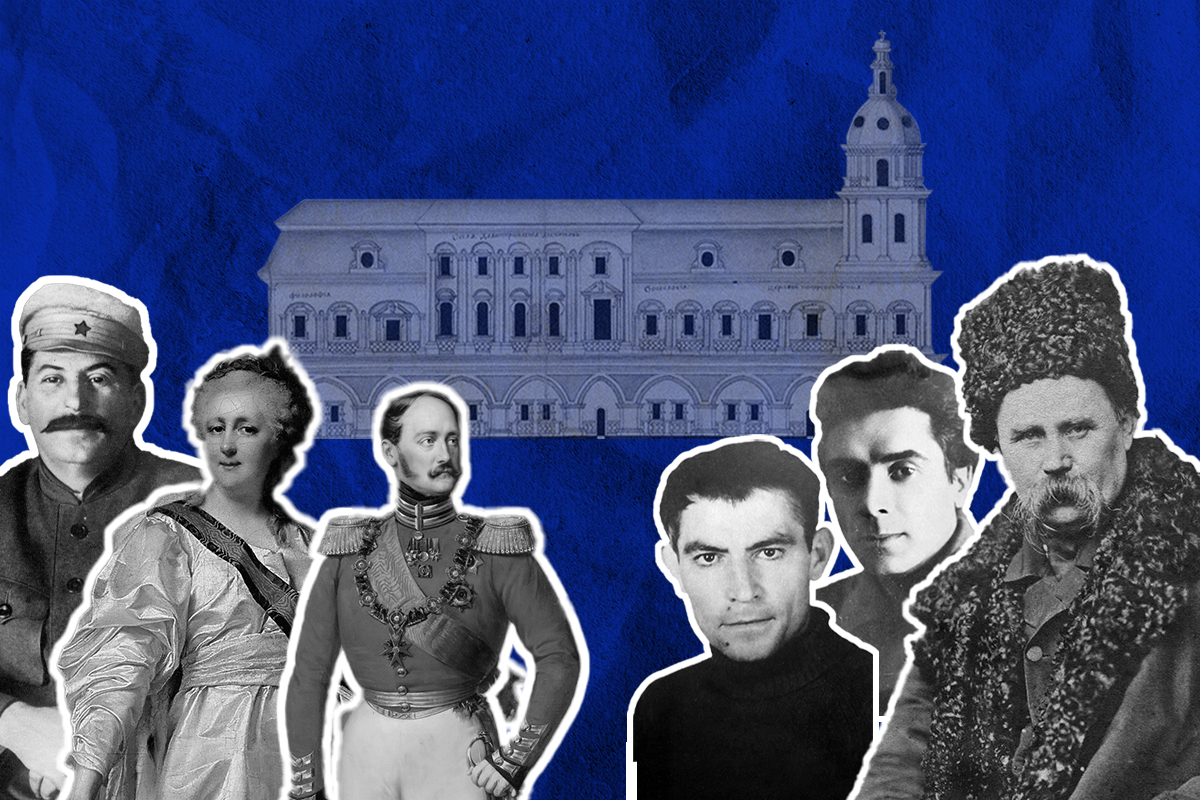

They trace back to the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union when Moscow consistently banned the Ukrainian language, restricting, persecuting, sentencing, and even executing Ukrainian artists, writers, and poets.

"The Russian Empire and the Soviet Union did not deny the existence of Ukrainians as a separate ethnic group. They denied the existence of Ukrainians as a separate nation," says Ukrainian historian Yaroslav Hrytsak.

"Because a nation has to have its own politics and its own culture."

Russian Empire

Russia has been trying to silence Ukrainian culture and language for the past 400 years when parts of what is now Ukraine fell under Russian influence.

"Oppressions lasted for several centuries, from the first restrictions during the reign of Peter the Great to the actual actions of the Russian regime today," says Deputy Head of National Remembrance Institute, historian Volodymyr Tylishchak.

As of the beginning of the 18th century, the Ukrainian cultural sphere was "as developed as the one in Poland, Lithuanian or Czechia," says another historian Kyrylo Halushko.

"There was book printing, high-class literature, and universities such as the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy," Halushko says.

"Of course, Moscow did not like that," he adds.

Aside from conquering Ukrainian lands, the Russian Empire — proclaimed in 1721 under Peter the Great (or Peter I) — sought to eliminate the Ukrainian identity, suppressing Ukrainian culture and language.

A year before the proclamation, in 1720, Peter the Great issued a decree against the use of the Ukrainian language in religious texts and books.

It was one of the first major steps toward banning the use of the Ukrainian language in public life.

In 1729, Peter II ordered the rewriting of the state regulations and decrees from the Ukrainian language into Russian.

Shortly after coming to power, Russian Empress Catherine II banned teaching in the Ukrainian language at the most prominent center of Ukrainian culture, the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. She also liquidated two autonomous Ukrainian entities – the Zapirizhzhian Sich and the Cossack Hetmanate.

Later, Catherine II ordered all the churches across the empire to conduct services only in the Russian language and made Russian compulsory for all schools. In 1786, the Russian language became the only language of teaching at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

"Catherine II decided to dissolve the Ukrainian ethnicity among other ethnic groups, to deprive Ukrainians of their national characteristics and identity and, ultimately, to destroy it completely," wrote Ukrainian political scientist Oleksiy Volovych.

But more severe measures followed in 1863 when the Imperial Interior Minister Pyotr Valuev issued a decree eliminating the publishing of books in Ukrainian.

The document said, "no special Little Russian language (meaning Ukrainian) ever existed, does not exist, and shall not exist."

The 1876 Ems Ukaz (Decree) issued by Emperor Alexander II only intensified the restrictions, banning imports of works in Ukrainian along with "stage performances, texts for sheet music, and public readings" in Ukrainian.

Hrytsak says both Valuev Decree and Ems Ukaz were "largely unprecedented."

"Russia declared the Ukrainian language as its enemy," he says. "The language as such was not banned. People could speak it in the villages or sing songs," he continues.

"It was (Russia's) way to not make it the language of public life and literature."

It was also Moscow's attempt to oppress the emerging spirit of Ukraine's national revival, or "the dangers for the state activities of Ukrainophiles," as stated in the Ems Ukaz.

Both documents were issued after a new generation of Ukraine's cultural figures formed a secret Kyiv-based society — the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius, which ignited the long battle between Ukrainian "intelligentsia" and Moscow authorities.

Among the brotherhood's members were acclaimed Ukrainian authors Mykola Kostomarov and Panteleimon Kulish.

Ukrainian writer and poet Taras Shevchenko, who became a symbol of the Ukrainian national movement in the 19th century, was even convicted for influencing the members of the society.

The brotherhood survived for less than two years. Soon after it was exposed, many of its members were either exiled or jailed, while some of their works were banned in the Russian Empire.

Hrytsak says both the foundation of the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius and the publication of Shevchenko's iconic collection of poems titled "Kobzar" have greatly intensified Moscow's "hostility" towards the Ukrainian language.

"Because that showed that it was not just a language," Hrytsak says. "There was a certain political idea behind it."

"Certain national ideology, which was separate from the Russian one, began to form in the times of Shevchenko," says Halushko.

That meant that "wherever there is the Ukrainian language — there must be Ukraine," he adds.

Soviet Union

Ukraine tried to escape Russia's dominance after its empire collapsed in 1917.

It was during the Ukrainian War of Independence (1917-1921) that the Ukrainian language was used for printing and in educational institutions.

But the formal ending to the Russian Empire did not mean its imperial narratives had disappeared: In 1922, Ukraine (apart from its western regions) was once again absorbed by Moscow into the newly formed Soviet Union. It became the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Just like imperial Russia, Soviet authorities did not deny Ukrainians as people. But they fiercely opposed Ukraine's right to be a nation.

To strengthen its power over Ukraine, as well as to show the West that any nation had its right to self-determination within the Soviet Union, the new regime initially launched a policy of so-called "korenizatsiia" or indigenization ("Ukrainization" for Ukraine), which appeared to be quite liberal but temporary.

It allowed schools and other educational facilities to switch to the Ukrainian language. Books, newspapers, and even films in Ukrainian were also freely produced.

At the same time, Soviet authorities wanted to present Ukrainian culture as "rural, outdated," according to Halushko.

Tylishchak says Ukraine's achievements and culture were deliberately simplified.

"In movies, for instance, there are many examples when Ukrainians are shown as silly villagers who sing funny songs," Tylishchak says.

In 1933-34, however, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin canceled "Ukrainization," as the authorities feared it could threaten their regime. Its end was accompanied by brutal repressions.

The lives of numerous Ukrainian cultural figures were destroyed for their pro-Ukrainian stance. They became widely known as the Executed Renaissance.

The spring of 1933 is believed to be the start of the Soviet Union’s mass destruction of the Ukrainian intelligentsia. On May 13, 1933, Ukrainian writer and intellectual Mykola Khvylovyi shot himself. In his suicide note, he spoke of the terror gripping Ukraine and criticized the Communist Party.

"His slogan 'Get away from Moscow!' related exclusively to the literary process, that Ukrainian culture should be oriented to Europe, not Russia," Tylishchak says.

Repression peaked in 1937 when numerous Ukrainian cultural figures such as writers Valerian Pidmohylny, Mykola Kulish, and Hnat Khotkevych, painters Ivan Padalka and Mykhailo Boychuk, were executed during the so-called Great Purge.

Renowned Ukrainian playwright Les Kurbas, the founder of the avant-garde Berezil Theater that staged plays in Ukrainian, was also shot.

"The theater's fate was tragic as well," says Tylishchak. "It was destroyed because it offered new forms of theatrical art."

According to Tylishchak, everything that did not correspond to the canons of Russia's propaganda back then was declared "bourgeois nationalism."

"Every Ukrainian artist, every Ukrainian scientist, and intellectual was constantly in danger of being accused of ‘Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism,’" Tylishchak says.

"It was one of the most terrible accusations in the Soviet Union."

Stalin's death in 1953 and the start of Nikita Khrushchev’s rule marked at least some easing of Soviet censorship of the Ukrainian language and culture — the so-called Khrushchev Thaw.

Tylishchak says there was a "new push for development" of Ukrainian culture in the 1960s when new "brilliant artists, poets, and writers appeared."

This new generation of creative Ukrainian youth who opposed the Soviet authorities was known as the Sixtiers. Famous writers Ivan Drach, Mykola Vinhranovskyi, Vasyl Symonenko, and painters Alla Horska and Liubov Panchenko were among its representatives.

"It wasn't a mass movement," says Tylishchak. "But the new impulse that Ukrainian culture received in the 1960s allowed it to survive (future) repressive politics," he adds.

Tylishchak says that "unfortunately," many of them ended up in Russian exile, "just like Vasyl Stus," a prominent Ukrainian poet who died in detention in 1985.

According to the historian, the Sixtiers also "gave an impetus" to the generation that regained Ukraine's independence in 1991.

Same old imperialism

Russia's centuries-long attempts to erase Ukrainian culture and language have also affected a newly-independent Ukraine: For many years, Ukraine's television, along with music and other industries, were mainly Russian-speaking.

The country's biggest newspapers were also published in Russian, not to mention streets and monuments named after Russian leaders across Ukraine.

A major shift started during the EuroMaidan Revolution in 2013-2014. It ended with Ukrainians ousting the pro-Kremlin regime and choosing its own future with freedom of speech and democratic values instead.

Modern Russia, on the other hand, was built on the ashes of the Soviet Union and hasn't refused the imperial ideas of its predecessors. Those views have only radicalized under its current dictator Vladimir Putin.

Led by Putin, Russia occupied Crimea in March 2014. It soon invaded Ukraine's east, occupying parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts.

According to Hrytsak, the "radical change in rhetoric" appeared in 2021, when Putin published an article on the Kremlin's website claiming that Ukraine “has never existed” and that "Ukrainians and Russians are one people, one whole."

In February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, bombarding cities all across the country. Parts of Ukraine were occupied by Russian troops as well.

The all-out invasion would soon prove that neither Russia's goal nor its methods have changed throughout the centuries.

"It wants to destroy the Ukrainian nation as such," says Tylishchak.

"To do so, Russia destroys Ukrainians physically, as we saw in Bucha and Borodianka, and tries to assimilate Ukrainians who ended up in occupied territories," he adds.

A month into the all-out Russian invasion, Russian troops began confiscating and destroying Ukrainian history and fiction books "that do not correspond with the Kremlin propaganda" in the libraries of then-occupied parts of Sumy, Chernihiv, as well as Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts.

According to Ukraine's Defense Ministry Intelligence Directorate, they had "a whole list of forbidden names," including Ukrainian Hetman Ivan Mazepa and controversial nationalist leader Stepan Bandera.

In Melitopol, an occupied city in Ukraine's southeastern Zaporizhzhia Oblast, Russian troops have seized all of Ukrainian literature from the local libraries, the Ukrainian military's National Resistance Center reported.

Ukrainian children's writer and poet Volodymyr Vakulenko was killed during the Russian occupation of a village near Izium, Kharkiv Oblast. Artist Panchenko died after a month of starvation in occupied Bucha, Kyiv Oblast.

In occupied Nova Kakhovka, Kherson Oblast, Russian troops have erected a monument to Soviet leader Vladimir Lenin. They have been stealing art collections from local museums and renaming the streets after Moscow leaders and their propaganda slogans.

"It's a cultural genocide against Ukraine," says Hrytsak.