It was at Kyiv’s Independence Square on Dec. 1, 2013, when Ukrainians gathered during the Revolution of Dignity to express their outrage over violent police crackdowns against protestors the day prior, that author Lyuba Yakimchuk’s then three-year-old son first learned the patriotic national slogan “Glory to Ukraine!”

“I wanted him to feel who we are,” Yakimchuk told the Kyiv Independent. “Later, he proudly took a small Ukrainian flag we had back at home, placed it on top of his toy ladder, and told me: ‘Glory to Ukraine!’ internalizing this new experience through play.”

In the early morning hours of Nov. 30, Berkut riot police armed with batons, stun grenades, and tear gas attacked peaceful demonstrators on Independence Square as well as nearby civilians. Most of them were students.

Ukrainians had gathered at Independence Square, or Maidan Nezalezhnosti, to protest then President Viktor Yanukovych’s refusal to sign an association agreement with the European Union in November 2013 in favor of strengthening economic ties with Russia. They endured months of brutally cold weather and police brutality, the latter of which claimed the lives of about 100 people, known today as the Heavenly Hundred.

Yanukovych fled to Russia in February 2014. Shortly thereafter, Russia unlawfully annexed the Crimean Peninsula and invaded Ukraine's Donbas region. The culmination of Russian aggression against Ukraine occurred in February 2022 with a full-scale invasion against the country.

Despite the challenges faced in the decade following the Revolution of Dignity, also known as the EuroMaidan Revolution, Ukrainian identity has coalesced around a robust civic society and a cultural renaissance that has provided strength and resilience in the face of ongoing Russian aggression.

Not only has Ukrainian identity embarked on a transformative journey since then, but so has European identity itself.

Strengthening civic society

The Revolution of Dignity should be acknowledged within the broader context of two preceding revolutions – the Revolution on Granite in 1990 and the Orange Revolution in 2004 – and generations of Ukrainians’ tireless struggle for independence.

However, it was the strengthening of Ukraine’s civic society which made the Revolution of Dignity stand out.

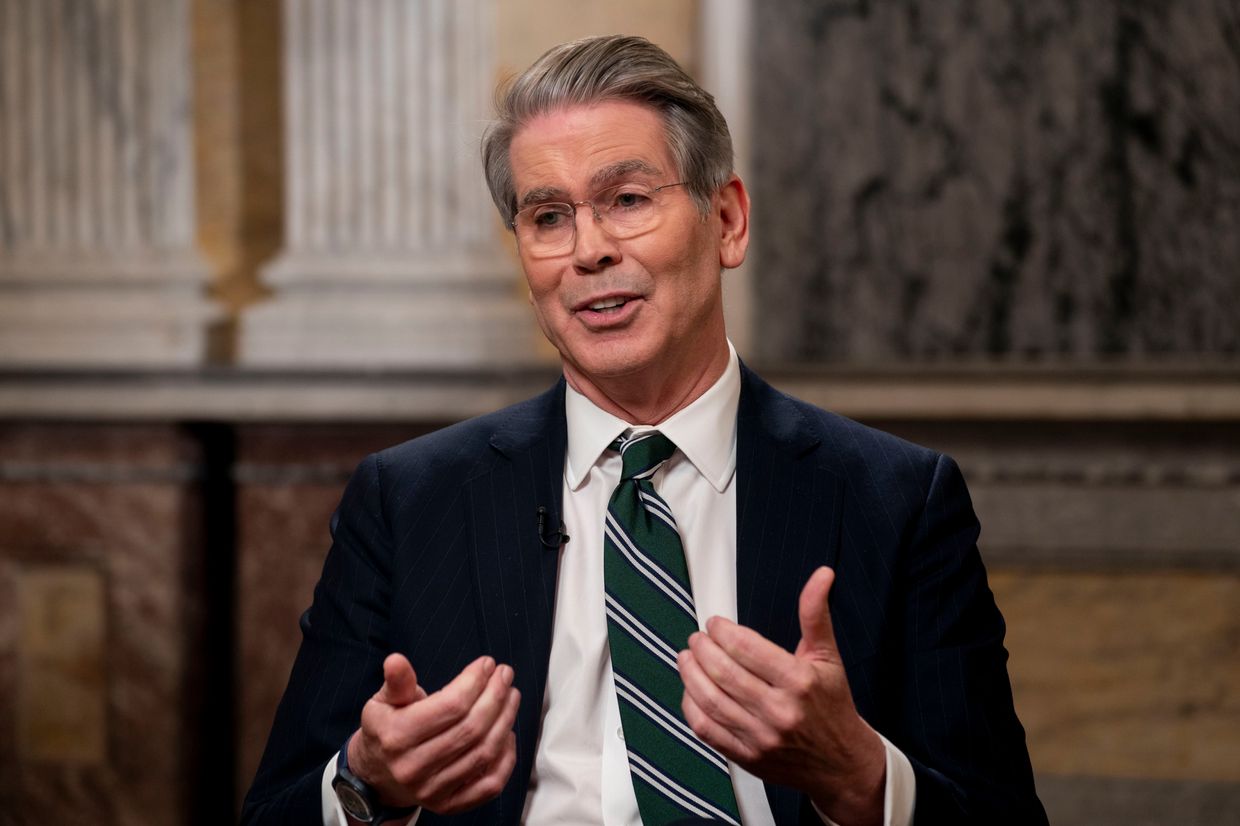

According to Serhii Plokhy, the Mykhailo Hrushevsky professor of Ukrainian history at Harvard University, all three revolutions had clear goals that they ultimately achieved.

The revolution leading up to Ukraine's independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 was known as the Revolution on Granite, occuring from Oct. 2-17, 1990. Dissatisfied with the recent Ukrainian parliamentary elections, the Ukrainian Student Union gathered at Kyiv's Independence Square, initiating a hunger strike.

The protest attracted participants beyond students and spread to locations outside Kyiv. Their main goal was to oppose the New Union Treaty, which would have seen to the Soviet Union's preservation.

During Ukraine's Orange Revolution, spanning from November 2004 to January 2005, people took to the streets to express their discontent with the results of the election runoff between ex-Prime Minister Viktor Yushchenko and then Prime Minister Viktor Yanukovych, as the rigged election results favored the latter.

Approximately 500,000 Ukrainians congregated on Kyiv's Independence Square to rally behind Yushchenko shortly after. Following a revote mandated by Ukraine's Supreme Court due to fraudulent election results, Yushchenko emerged as the ultimately successful candidate in a revote and assumed the presidency.

Yanukovych would go on to become president in 2010, but the Revolution of Dignity in 2014 proved to be his downfall. Each revolution brought Ukraine one step closer to becoming a truly independent state.

“The revolution of 1990 paved the way to Ukraine’s independence, the revolution of 2004 defended Ukraine’s democracy, and the revolution of 2014 set the course for the country’s European integration,” Plokhy explained.

Recognizing the inherent challenges on the path toward European integration, particularly amid the backdrop of Russian aggression that ensued in the aftermath of the revolution’s success, Ukrainian civic society has maintained its momentum.

“The protestors (of the Orange Revolution) helped to elect the president they wanted and then went home,” Plokhy said.

“But in 2014, they stayed mobilized, taking part in political life and taking responsibility for what would come next. The Revolution of Dignity helped solidify concepts of responsibility and engagement in Ukrainian society. The more we have of that in the future, the better.”

Ukraine's younger generations, shaped by the backdrop of revolutions against corruption and Russia’s war against their country, have internalized this lesson.

Julia Tymoshenko, who works in marketing and communication for the nonprofit Saint Javelin, remembers being told by her father from childhood about her Cossack ancestors and how her great-great grandparents had survived the Holodomor, the Soviet man-made famine that killed an estimated 3.5-5 million Ukrainians between 1932-33.

“But up until 2014, that was just history to me, something that happened in the past. I didn’t quite realize that Ukraine’s fight for freedom from the Russian Empire had never fully stopped,” Tymoshenko told the Kyiv Independent.

As an international exchange student in the years following the revolution, she jumped at every opportunity to explain to classmates and teachers abroad how Ukraine was not a “small part of Russia.”

“For some people, it wasn’t a big deal. But for me, there was a clear connection between the Russian invasion of Ukraine and a Russian flag above Ukrainian national dishes in the school dining hall.”

After the full-scale invasion of 2022, she became one of many young people that devoted themselves to actively aiding in fundraising for the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

Breaking away from empire

Once more Ukrainians realized the danger of “being absorbed by Russia and turned into a second Belarus,” a greater interest in their own culture developed and they understood that it is “precisely what defines us internally,” according to Yakimchuk.

The Russian Empire and the Soviet Union, historically, relegated Ukrainian culture to the margins, deeming it as something kitsch and not worthy of the respect accorded to Russian language and culture.

In eastern Ukraine, where many major cities had long been predominantly Russian-speaking, with Russian propaganda since 2014 attempting to convey them as "repressed" by the Ukrainian state, the linguistic shift to Ukrainian was a matter of self-preservation and returning to their roots.

Being told they were being "saved" by Russian tanks and missiles only accelerated the process from 2014 and particularly 2022 onward.

Sasha Dovzhyk, author and special projects curator at the Ukrainian Institute in London, hails from the southeastern city of Zaporizhzhia. She once considered Russian her mother tongue, cultivated friendships in Russia, traveled there, and expressed solidarity with Russian opposition activists. But the Revolution of Dignity in 2014 made her rethink all of that.

“Russia ramped up its Ukrainophobic rhetoric during the Revolution of Dignity, creating artificial divisions within Ukrainian society and using the Russian language as a weapon against Ukrainians,” Dovzhyk told the Kyiv Independent.

This became increasingly apparent as Russian propaganda outlets portrayed the revolution as a coup orchestrated by malevolent forces, rather than a major grassroots movement stemming from peaceful student demonstrations. Russia also sought to downplay its invasion of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts by characterizing it as a "civil war," with false claims that separatists were fighting to break free from Ukraine.

As a result, remaining ties between Ukraine and Russia began to weaken. Some Ukrainian artists, whose work was enjoyed by audiences in both countries, even opted to sever ties with Russia altogether.

Ukraine’s most famous rock band, Okean Elzy, refused to perform in Russia after the illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014. Meanwhile, Ukrainian pop stars like Maruv withdrew from the 2019 Eurovision competition as Ukraine's contestant amid public backlash for continuing to perform in Russia.

Maruv had claimed at the time that performing concerts in Russia was her way of “bringing peace” but Ukrainians understood that Russia strategically uses its culture as a tool of war.

As Ukrainians embraced a cultural renaissance in the wake of the revolution, they observed pushback from Russians, including those who were ostensibly anti-Putin.

“I had expected those Russian friends to actively support the Revolution of Dignity and start a similar anti-authoritarian movement at home back then. I was naive. They felt threatened and confused by the Ukrainian national revival manifested at the Maidan,” Dovzhyk said. “Some of them eventually supported the Russian annexation of Crimea.”

Yakimchuk added that this was all tied to the Russian imperial mindset: “Empires are designed to destroy the cultures they set out to colonize.”

For Dovzhyk, one of the most inspiring examples of Ukrainian defiance against Russian imperialism is filmmaker Oleh Sentsov. A participant in the EuroMaidan Revolution in Kyiv, he was arrested for opposing the illegal annexation of his native Crimea, forcibly brought to Russia, and sentenced to 20 years in prison on made-up terrorism charges.

In a Russian courtroom, Senstov vehemently denounced the annexation and refused to be tried as a Russian citizen. He even went on hunger strike for 145 days to demand the release of all the Kremlin’s Ukrainian political prisoners.

He was freed in a prisoner exchange in 2019, and since 2022, he has been serving in the Ukrainian military in some of the most dangerous parts on the front line.

“The courage and resolve of a man who was powerless in regard to external factors but who used the only weapon he had–his voice–to fight for the freedom of others is what distinguishes Ukrainian national identity for me,” Dovzhyk said.

Cultural renaissance

In the decade following the Revolution of Dignity, the Ukrainian government has taken important steps to promote Ukrainian language and culture in all spheres of public life, including education, media, sports, and even religion.

Ukraine's Soviet history is one of many cultural aspects that Russia sought to exploit in its aggression against the country. Russian dictator Vladimir Putin even claimed in February 2022 that the full-scale invasion was meant to “de-Nazify” Ukraine, despite the fact that millions of Ukrainians fought and died against the Nazis in World War II.

The Verkhovna Rada, Ukraine’s parliament, passed decommunization laws in 2015, which banned Communist and Nazi propaganda and symbols.

One of the provisions under these laws was that the names of Ukrainian towns, cities, and villages changed by the Soviets were returned to their previous names, or changed to an entirely new name if there was no precedent.

A famous example is the town of Novhorodske in Donetsk Oblast, which resumed being known as the town of Niu-York in 2021, a name which dates back to the 19th century, when Mennonites from the city of Jork in northern Germany settled in the region.

The law "On Protecting the Functioning of the Ukrainian Language as the State Language," which was passed in 2019, also established quotas of varying degrees on the public use of the Ukrainian language.

The number of Ukrainians solely using the Ukrainian language has continued to rise over the past decade. This trend has always relied on multiple factors relating to public and private life.

A survey conducted by the Kyiv Institute of Sociology showed that at the end of 2022, 44% of Ukrainians spoke only in Ukrainian in daily life, compared to 34% in 2017. Meanwhile, 50% of those respondents spoke only in Ukrainian at home, compared to 37% in 2017.

Eighty percent of respondents to the survey believed that Ukrainian should be the primary language in all spheres of communication, compared to 60% in 2017.

This upward trend applies to reading preferences as well. The corporate office of Yakaboo, one of Ukraine’s top online book sellers that is currently used by more than 3.5 million people worldwide, told the Kyiv Independent that estimates from sociologists and market players pointed to approximately 50-60% of Ukrainian readers preferring Ukrainian-language books over the past decade.

Book imports from publishers in the Russian Federation were banned by Ukraine in 2016, but some Ukrainian publishers still offered selected titles in Russian translation. After the full-scale invasion in 2022, that demand dropped significantly. Ninety-four percent of the books sold last year by Yakaboo were in Ukrainian.

When it comes to religion, Russia historically relied on the influence of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Moscow Patriarchate (UOC-MP).

The UOC-MP was once the largest Orthodox church operating in Ukraine. However, it still follows religious leaders in Russia. Its church leaders have been charged by Ukrainian authorities for their pro-Russian statements and even support of Russian occupation.

The independent Orthodox Church of Ukraine held its first Christmas service in Ukrainian at the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra, the country’s main Orthodox monastery, in January 2022.

Despite state-level efforts, language and culture remain personal journeys in many Ukrainians’ lives, with such changes unfolding gradually.

But as Russia’s all-out war continues, and stories continue to emerge from Russian-occupied territories of Ukrainian books being burned and teachers being targeted for their pro-Ukrainian stances, many Ukrainians have underscored the urgency of this process for the sake of future generations.

“We need to continue to engage in the decolonization of our culture and thinking here in Ukraine. Even now, many people cannot live without Russian culture – they show Russian cartoons to their children, continue to consume content from Russian-language YouTube,” Yakimchuk said.

“To make it easier for our children, the process of decolonization must happen now, and we must be the ones to sever ties with the aggressor.”

European future

Ten years after Ukrainians gathered on Independence Square to protest against Yanukovych’s failure to sign an association agreement with the EU, they were welcomed by the European Commission’s historic decision on Nov. 8, 2023 recommending formal talks on Ukraine’s EU membership.

Ukraine faces a long road ahead when it comes to achieving all its democratic reforms and officially becoming a member of the EU.

But the Revolution of Dignity and its preceding revolutions remain positive examples for Ukrainians and the world, whereas other revolutions in the region have failed over the years.

As Plokhy pointed out, this recent milestone serves as evidence that, in the broader context, Ukraine is making significant strides toward victory:

“Russia has been waging a war now for close to 10 years trying to stop Ukraine’s push toward EU membership, claiming among other things that no one wants or awaits Kyiv in Europe. The start of the negotiations for Ukraine’s admission to EU is one more proof that Russia is losing this war.”

Volodymyr Yermolenko, author, president of PEN Ukraine, and lecturer at Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, told the Kyiv Independent that a decades-long struggle was always to be expected.

“Change cannot always come quickly and easily. Every revolution demands evolution, and this inolves the difficult work of a country’s citizens over generations. I think that Ukrainians need to fully embrace this sense of a multi-decade struggle. Unfortunately, now it is primarily a military struggle.”

Yermolenko contends that Ukraine's EU membership prospects have evolved into a security concern over the last decade, shifting away from just values-based and economic considerations.

However, the EU is struggling with an ongoing reluctance to frame itself in the context of security and hard politics, despite the majority of its members being affiliated with NATO, a military alliance.

“With American politics being so unpredictable, the EU really should think about how to ensure its own security and the security of the European continent. It needs to get back to politics and let go of the refusal to think of itself in terms of security and hard power in a positive sense,” Yermolenko said.

Ultimately, this is why the very prospect of Ukraine’s EU membership, which began as a dream for millions of Ukrainians on Kyiv’s Independence Square a decade ago, “will change not only Ukraine and eastern Europe, but Europe as a whole and promote a rethinking of the European project.”

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan, thanks for reading this important story. It was a privilege for me to interview Ukrainians about their experiences during the EuroMaidan protests, one of the first major events in Ukrainian history that sparked my own interest in the country. I hope you gained greater appreciation for Ukraine's fight for freedom while reading, and if you like this sort of thing, please consider supporting The Kyiv Independent.