Editor’s Note: The names of Crimea’s former and current residents cited in this article were changed to protect their identity amid security concerns.

When Ukrainians talk about Crimea, they often talk about memories. For many, this peninsula surrounded by the Black Sea was a place where they spent long summer days enjoying beautiful nature and rich cultural life.

But they also talk about war. Russia’s invasion of Crimea on Feb. 20, 2014, which coincided with the deadliest days of the EuroMaidan Revolution, marked the beginning of the most tragic events in Ukraine’s modern history.

Taking advantage of the havoc in Kyiv following the ousting of ex-President Viktor Yanukovych, Russia quickly seized military bases and government buildings in Crimea. In March 2014, Moscow staged a sham, internationally unrecognized referendum on joining Russia and illegally annexed the peninsula.

What followed was the transformation of Crimea into a highly militarized, subsidized, and isolated territory. Over the last 10 years, Moscow has carried out a series of neo-imperialistic policies on the peninsula central to Kremlin propaganda.

As Ukraine moves forward in its efforts to push Russian troops out of Crimea, disabling around 20% of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet and launching strikes on crucial military facilities in Crimea, there has been an increased hope that Kyiv could liberate the peninsula.

But what would a liberated Crimea look like after ten years of Russian occupation?

Economy

Before the Russian occupation, most Crimeans were employed in trade, agriculture, manufacturing, and services. Since 2014, exports from the peninsula have significantly decreased, and foreign companies exited the market due to sanctions, making Crimea largely dependent on the Russian federal budget.

Subsidies from Moscow have varied over the years but still constitute two-thirds of the Crimean budget, according to the Crimean service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL).

The focus of the Crimean economy also shifted toward the military-industrial complex as Russia revived Soviet-era military factories and built new infrastructure.

When Crimean residents started receiving salaries and pensions in rubles, Russia gave state employees “a better transfer rate,” which meant a temporary increase in income, experts told Ukrainska Pravda. But as Ukrainian products in stores were replaced with Russian ones and the ruble’s value went down, prices in Crimea spiked.

“We could go out with a friend after work (before the annexation). Then suddenly there was a lack of money; I remember that I couldn’t even buy sneakers for myself,” Maria, a resident of Crimea, told the Kyiv Independent.

Crimea was placed among the 10 Russian regions with the lowest level of income in a ranking prepared by the Russian state-owned RIA Rating Agency in 2023.

Infrastructure

After the annexation, Russia began turning Crimea into its showcase window, building and repairing roads, schools, parks, public spaces, and other infrastructure.

Russia launched several huge and expensive projects like the 250-kilometer-long Tavrida Highway connecting the peninsula’s eastern part with its southern coast and the $3 billion Kerch Bridge that links Crimea to Russia.

“It felt like Putin wanted people to understand that Russia is a powerful state. At the same time, nothing (like this) was built in other regions of Russia,” Yurii, who left the peninsula after the start of the full-scale invasion, told the Kyiv Independent.

“All this has managed to form in some people the opinion that Russia really cares about the Crimeans.”

The Tavrida Highway, put in operation in 2020, has reportedly begun to collapse, leading to multiple road accidents, while the Kerch Bridge was not fully restored after Ukrainian attacks, Ukraine’s Southern Command said in December last year.

Intensified construction on a relatively small territory of Crimea full of nature reserves and recreational areas has also harmed the peninsula’s ecology, endangering its rare animals and plants and changing its landscapes.

“The occupiers began to treat the Crimean environment as colonizers…The protection of the environment ... has been ignored for the sake of the occupation administration's political, economic, and military goals,” Yevhen Yaroshenko, an analyst of the Crimea SOS NGO, told RFE/RL in March last year.

Population

As another part of its neo-colonization efforts, Russia has created a number of incentives for Russians to move to Crimea, offering them job opportunities, preferential mortgage lending, and even reportedly giving Russian soldiers confiscated homes of Ukrainians who have refused to accept Russian citizenship.

Military and state employees in Russian-occupied Crimea also receive significantly higher salaries and more social benefits than those employed in other sectors.

At the same time, many Ukrainians who didn’t flee occupation have been expelled, imprisoned on political grounds, pushed to move to Russia, or mobilized into the Russian military.

Up to 800,000 Russians have illegally moved to Crimea, while around 100,000 Ukrainians have left the peninsula since its annexation as of December 2023, the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union reported.

“It feels as if there are practically no Crimeans left in Crimea. This is the feeling you get when you are looking for a job. Now, even all the managers at the hotel where I worked, the directors, and deputies are all from (Russia),” said Maria.

The mass resettlement of Russians in Crimea and the deportation of Ukrainians from the peninsula violates international humanitarian law, according to the union. This policy may also constitute a war crime and a crime against humanity.

Education and Russification

Moscow’s efforts to Russify Crimea have also focused on education. Ukrainian history and literature classes in Crimean schools have been canceled, and the number of children learning the Ukrainian language has sharply decreased.

Before 2014, all Crimean schoolchildren studied Ukrainian, with around 7% learning all subjects in the language. By 2023, this proportion dropped to 0.09%, which means only 197 children out of 230,000 were studying in Ukrainian, according to the Almenda Center for Civic Education.

The UN’s International Court of Justice concluded in January that Russia had violated the right of Ukrainians in the annexed Crimea to receive education in their native language.

At the same time, schools in Crimea have been heavily militarized, and local children are subjected to the so-called “patriotic education.”

“They force children to make drawings for Russian soldiers… bring socks and other clothes (to be sent) to the military,” Maria said, describing Crimean schools amid the full-scale invasion. “A lot of propaganda. As if the children were already little soldiers.”

Surrounded by narratives that Crimea “has always been Russian,” praising the illegal annexation as a “long-awaited return,” Crimeans are afraid to even identify as Ukrainians. Maria said that she was assaulted after telling Russian soldiers in a Crimean cafe, who were intimidating her, that she was Ukrainian.

According to Yurii, under years-long pressure of Moscow-imposed ideology, Crimeans have developed self-censorship, often preventing them from expressing their genuine opinions.

“On a subconscious level, you understand that it’s better not to say too much,” Oleksandra, who left Crimea in 2021, told the Kyiv Independent.

“There are a lot of police and cameras; it’s like you’re under surveillance 24/7. It really bothered me, this feeling of being watched over.”

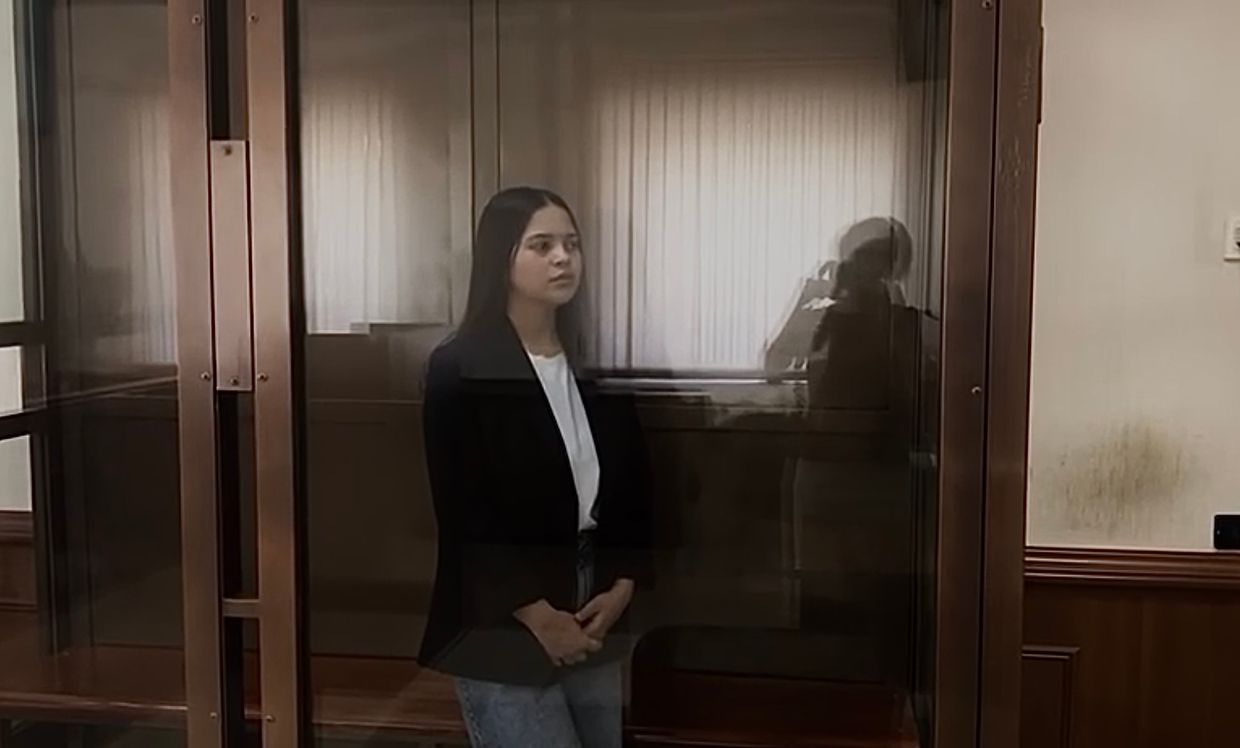

Repressions

The indigenous Muslim population of Crimea, the Crimean Tatars, have been especially outspoken against the Russian occupation, making them the main target of Russia’s repression machine.

They have been routinely searched, interrogated, baselessly accused of terrorism, arrested, and sent to prisons thousands of kilometers away from their homes, a Crimean Tatar activist told the Kyiv Independent.

Most cases against Crimean Tatars cite alleged links to the Hizb ut-Tahrir pan-Islamist political party, which operates legally in Ukraine and most countries but is banned in Russia.

Throughout the 10 years of Russian occupation, 307 residents of the peninsula, mostly Crimean Tatars, were imprisoned or criminally persecuted on political grounds, the Crimean Tatar Resource Center said on Feb. 7. Out of this number, 55 prisoners have been released so far.

In prisons, Crimean Tatars are denied access to medical assistance, put in isolation cells, and stripped of their rights to communicate with relatives and lawyers and practice their religion, according to the Crimean Tatar activist the Kyiv Independent spoke with.

Two Crimean political prisoners died in 2023, and 40 more are under such risk due to the lack of medical assistance, according to the Ukrainian human rights center Zmina.

What has changed after the full-scale invasion?

After the beginning of the all-out war against Ukraine in 2022, Russia tightened its grip over Crimea, as if in fear of losing the peninsula, further militarizing its society, doubling down on propaganda, and intensifying repressions.

In addition to fabricated terrorism charges, Crimeans now risk being persecuted for anti-war statements. As of late December last year, Russian occupation authorities in Crimea reportedly opened over 500 administrative cases over “discrediting the Russian military.”

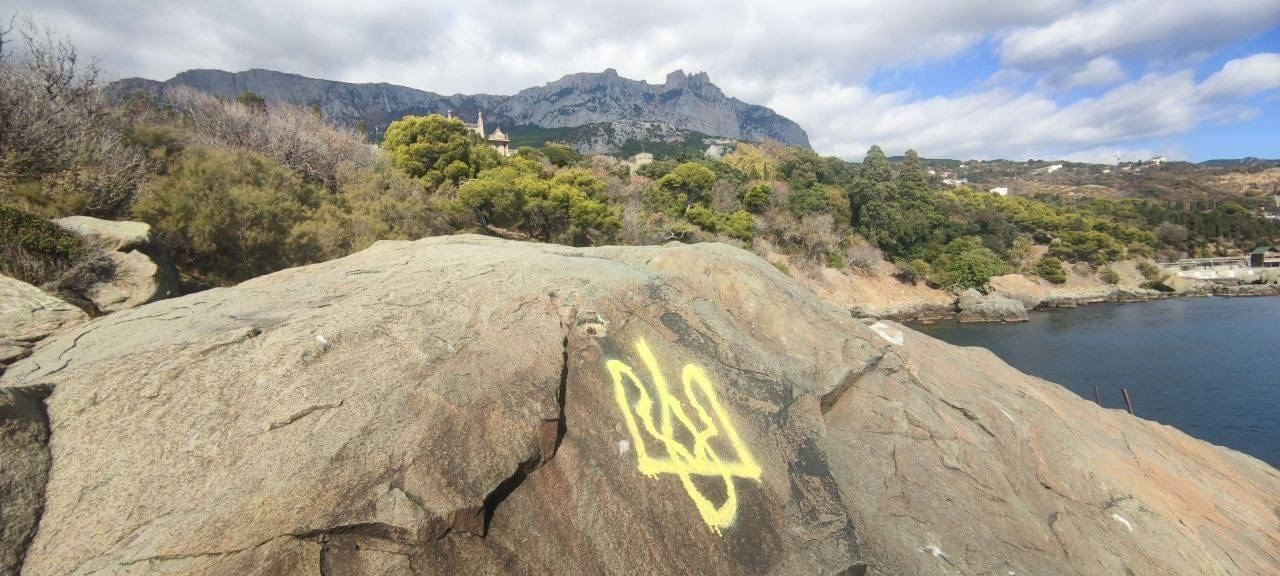

The increased pressure from authorities and Russia’s mobilization campaign for the Ukraine war prompted another wave of emigration from Crimea. Some pro-Ukrainian residents chose to stay and engage in various resistance activities, sometimes paying for their views with their freedom.

Tamila Tasheva, President Volodymyr Zelensky's permanent representative for Crimea, told the Kyiv Independent that there wasn't "such a tangible resistance" on the peninsula before 2022.

As Kyiv has vowed to liberate Crimea, local partisans have played a key role in aiding Ukrainian military operations on the peninsula.

The renowned resistance organization Atesh claims to have directed Ukrainian strikes on Russia’s Black Sea Fleet headquarters, the Minsk and Rostov-on-Don warships, airfields in Saky and Dzhankoi, as well as other Russian targets in Crimea.

Around 2,000 people from Crimea and Russia have joined Atesh, including some Russian service members, one of the movement coordinators told the Kyiv Independent. Most of them reside on the occupied peninsula, which means they are constantly at risk of being captured by Russian special services or even killed.

“All agents understand this, but they take such a risk because they realize the importance of their work,” the coordinator said.

“Some want to take revenge on Russia for all the crimes it commits, some want to make efforts to stop the war. However, the majority of our agents want to work for the liberation of Crimea from Russia and its return to Ukraine.”

Potential liberation

Ukraine is already actively preparing for Crimean reintegration, recruiting future employees of the local government, developing a new humanitarian and information policy, and discussing changes to the legislation on collaborators.

Kyiv sees liberated Crimea as “a free, economically independent region… with the concept of a year-round resort, which relies on local small and medium businesses; a territory where the rule of law and justice prevails,” according to a document cited to the Kyiv Independent by Tasheva.

However, reintegrating a population that has been isolated from the Ukrainian information space and all the processes happening in the country following the EuroMaidan Revolution while being brutally colonized by Russia will be challenging.

According to the current Ukrainian legislation, more than 200,000 people in Crimea could be held responsible for collaboration after the liberation, Tasheva said in May last year. Ukraine may also expel some Russian citizens who came illegally to Crimea after annexation, she told Newsweek last summer.

Reintegration is “a complex process and requires an individual approach,” Tasheva said to the Kyiv Independent, but Ukraine can still borrow some practices from other countries that have similar experiences, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Cyprus, Germany, and South Korea.

“One of the key decisions of these countries was investing in the future — the modernization of the education system, investment in science and the involvement of new technologies in the IT sphere, creation of an encouraging environment for the development of (local) business and economy.”

Maria said that since the start of the full-scale invasion, she noticed more people voicing their hopes for a return to Ukraine, but many have already lost hope that it would happen. Some are afraid they might be considered traitors after liberation, she added.

The general feeling of uncertainty widespread in Ukraine as the all-out war enters its third year is also felt in Crimea, only strengthened by the pressures and dangers of Russian occupation, Anastasia from Dzhankoi told the Kyiv Independent.

“When Kherson was liberated… this victory brought people the belief that all other occupied territories could also be liberated in the same way,” according to Anastasia, but the mood among Crimeans has worsened as Ukraine’s latest counteroffensive didn’t meet expectations and Russia took more territory in the east.

“People are confused… They are not sure that the liberation of Crimea is possible in the near future, and at the same time, they do not want to endure these repressions for several more years… They have no idea of what their future will be.”

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Dinara Khalilova, the author of this article. When talking to Crimeans, who have endured occupation for a decade, I was amazed at their ability to keep their spirit high and hold on to that hope for long-awaited liberation. But one of their strongest fears is to be forgotten. To keep telling such stories about life in the Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine, we need your support.