Editor’s note: The Kyiv Independent traveled into Russia’s Kursk Oblast with Ukrainian soldiers during the ongoing Ukrainian cross-border offensive in the area. Since the trip constitutes an unsanctioned crossing of the state border between Russia and Ukraine, the identities of the author of the report and of the soldiers are not being disclosed for security reasons. The inclusion of all other details in the report has been done with maximum respect to operational security. We believe that the high public interest justifies the risks of the crossing.

SUDZHA, Russia – At the official state border crossing point between Ukraine and Russia, not a single building is left untouched: What were once large customs offices, service buildings, and duty-free shops had mostly been reduced to piles of metal and brick mangled beyond recognition.

On Aug. 6, this place where cars and trucks would once line up on the pothole-covered road for the mundane routine of a state border crossing, suddenly became ground zero for the first invasion of Russian territory since World War II

On the Russian side of the crossing point, a large makeshift sign spray painted with the work “SUDZHA” shows the route for those who now make up all of the border traffic: Ukrainian soldiers on the offensive.

“When I came across, I couldn't believe my eyes,” said Serhii, one of the Ukrainian soldiers who escorted the Kyiv Independent into Russian territory, whose name has been changed to protect his identity.

“It was really cool, a lot of adrenaline,” he said. “I mean, I was dreaming for a while about entering Crimea, but this here was something else, it felt like we really dealt Russia a blow.”

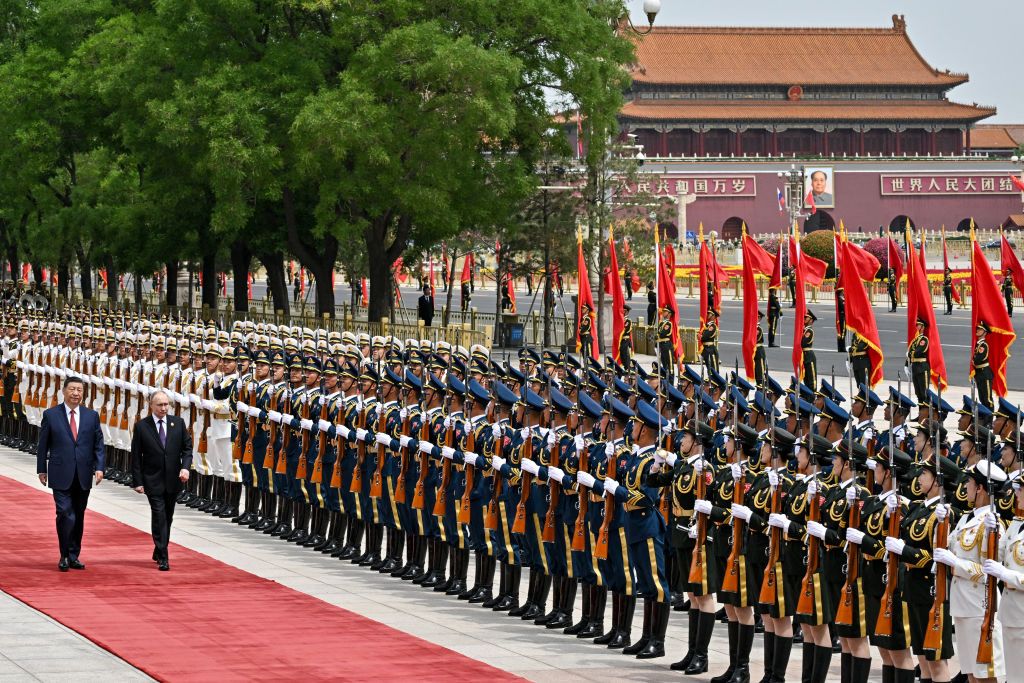

Coming as a surprise to civilians, observers, and even Western governments, Kyiv’s bold offensive into Kursk Oblast signaled quickly that it would be more than just a short cross-border raid.

Now, with more Ukrainian brigades committed to the fight and Russia heavy-handedly deploying forces in response, Kursk Oblast promises to be a new, fully-fledged arena of the war for a significant time going forward.

As much as the early phase of the incursion proved a stunning success for Kyiv, the final goals of the Ukrainian military in Kursk Oblast remain murky.

President Volodymyr Zelensky has claimed that the main goal is the creation of a “buffer zone” to protect neighboring Sumy Oblast from Russia potentially launching a cross-border offensive of its own.

Strictly militarily, the offensive also aims to force Moscow to redirect some forces from offensive operations in Donetsk Oblast, though over the past two weeks, Russian advances on the key city of Pokrovsk have shown no sign of slowing down.

On Aug. 20, Ukrainian Commander-in-Chief Oleksandr Syrskyi announced that Ukrainian advances into Russian territory measured at up to 35 kilometers.

According to the top general, Ukrainian forces have now captured 93 settlements across an area allegedly measuring 1,263 square kilometers.

The Kyiv Independent traveled across the border to Sudzha with two Ukrainian soldiers, spending a little over an hour inside the town’s administrative area before crossing back into Sumy Oblast.

On top of legal questions surrounding an unsanctioned border crossing, covering the incursion inside Russian territory accompanied by members of an invading military, also presents an unprecedented ethical minefield.

These lands, from which tens of thousands of Russian civilians have fled, are now effectively under Ukrainian military occupation, a picture that can be hard to comprehend after over 10 years of Russia occupying and invading parts of Ukraine.

Just past the border crossing point, a white Lada with a Russian flag decal lies abandoned, its windows riddled with gunshot holes.

Just behind the car, rows of concrete “dragon’s teeth” anti-vehicle fortifications can be seen stretching across the overgrown fields of the Russian borderlands.

“They don’t seem to have worked,” joked Serhii.

In the days and weeks before the offensive, Ukrainian brigades began to gather around the border in Sumy Oblast, often unaware of the movements of other units in the area.

In the end, many Ukrainian soldiers learned of their new orders just a day prior to going in.

“Everything happened so spontaneously and quickly, at first when the command came down we thought they were joking,” recalled Serhii.

“I thought at the time that the hope was to just distract the enemy from another operation somewhere else. But as I saw how many of our guys were going, I saw it was something big.”

Two weeks into the launch of the incursion into Kursk Oblast, the town center of Sudzha, which once had a population of just over 5,000 people, is a quiet and desolate place.

Littered with broken glass and other debris, the central square is now without its statue of Soviet Union founder Vladimir Lenin, as Ukraine’s policy of decommunization extended into the newly-captured Russian territory.

Within a short radius, all the typical signs of a small Russian town can be found: the beat-up state-run post office, supermarkets from country-wide chains, and of course, a World War II memorial.

A stout building to one side of the square hosts the town’s tax service.

Apart from some broken windows and light damage, the building stands empty of people but intact, as if time had simply stopped.

Morning sunlight floods into offices filled with indoor plants, shelves full of paperwork, and fridge magnets from across Russia and occupied Crimea.

Only five days prior, a report from Ukrainian state-backed television had shown the Russian flag being removed from a building, with Moscow still claiming that fighting for the town was ongoing.

Now, although available mapping of the front line shows fighting taking place only around five kilometers away, Sudzha mostly feels like a settlement further in the rear.

Outgoing artillery fire can be heard in the distance, but the sound of incoming artillery or drones flying above is a rarity, in contrast to what somewhere at a similar distance to the front line might sound like in eastern Ukraine.

The first phases of the Kursk offensive were shaped by rapid maneuver warfare, as Ukrainian troops quickly flooded across the state border, thinly-manned by a mix of mostly border guards and conscripts.

This, however, is changing.

“The quick phase is over,” said Yurii, whose name has also been changed, a Ukrainian medic serving in a different brigade, which had taken part in the earliest attacks on the border crossing post.

“The greatest effort was at the start, but apart from a village here or there, we are not advancing anywhere near as much anymore.”

Though Ukrainian advances have been reported to have slowed down in the direction of Kursk itself, the recent destruction of three bridges along the Seim River further west of Ukrainian-held territory indicates Kyiv’s potential attention to secure another large slice of Kursk Oblast by incapacitating Russian logistics south of the river.

Meanwhile, Moscow, which on Aug. 20 created three new military groupings for Kursk, Bryansk, and Belgorod oblasts, looks to be gradually upping efforts to push Ukrainian forces out of Russia.

“They have brought in a lot of forces now,” said Yurii, “forcing us to send more of our own in and turning this all into a real s***show.”

“They are digging in, and we will need to dig in too. If we wanted to have a big breakthrough again, we will need a new grouping of forces similar to the first one we gathered.”

Though Russia’s use of their trademark devastating glide bombs was made much more difficult in the early days of the incursion, soldiers speaking to the Kyiv Independent reported an uptick in glide bomb attacks over the second week of the operation, both on occupied settlements inside Russia and on Ukrainian villages along the border.

The same also goes for FPV (first-person view) suicide drones, which could sporadically be heard flying around the town.

Walking around the empty streets of Sudzha, it’s difficult not to draw comparisons to the early days of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Although there are no verifiable figures on civilian casualties as a result of the incursion, Kyiv’s operation has inevitably brought desolation to these parts of Kursk Oblast.

This is visible enough among the animals: dead cats and dogs can often be seen lying on the roadside, while groups of ducks, chickens, and sheep roam the town’s streets in search of food and water under the hot August sun.

As for Sudzha’s human residents, Russian civilians can be occasionally seen walking and cycling around their town.

Most of Sudzha’s population was able to leave the town by their own means, with multiple reports of little to no assistance with evacuation from Russian local or regional authorities.

For those left behind, for now, no humanitarian corridors have been agreed upon to evacuate civilians back to Russian-controlled territory.

“When it all started, my daughter and grandson were in Kursk, and they were calling, telling me 'Grandpa, we will come and get you as soon as we can!'” said Anatoly, a 68-year-old resident of Sudzha, who was approached in the company of Ukrainian soldiers while on his bicycle.

“But they couldn't come in the end, and I couldn't leave my animals, so here I am.”

In scenes similar to those in Ukrainian cities occupied by Russia amid heavy fighting, many local residents here chose to remain in basements until the situation settled down, only to emerge and find soldiers of a foreign army patrolling their homes.

Wearing old eyeglasses repaired with makeshift wires, Anatoly speaks cordially to Serhii and the other soldiers, repeatedly saying “thank you guys” in a tired but composed tone.

“At first I didn't know what to do, I just stayed in my basement for three nights,” he recalled.

“Eventually, one of your (Ukrainian) commanders got me out of there and took me to Magnit (a Russian supermarket chain) to collect some food for me. And that's it.”

Still, with Ukrainian soldiers present, discussing their true feelings about the war or the Russian leadership in such situations is unlikely to result in honest answers.

After the frantic early phase of the operation passed, Ukraine’s leadership announced the creation of a military administration in parts of Kursk Oblast.

The priority for now is restoring the supply of running water to the town, while centers for humanitarian and medical aid have also been established.

What happens further — whether or not Kyiv intends to set up a more comprehensive occupation administration — will depend on the battlefield, and on how long Ukraine intends to hold this remote chunk of Russian borderland.

Of all the visual ties to Russian occupation in Ukraine, one similarity jumps out more than any other: spray-painted text on gates and fences reading “Peaceful people live here” or just “PEOPLE,” which is spelt identically in Ukrainian and Russian.

The image harks back to the sudden occupation of towns like Bucha and Irpin in Kyiv Oblast and other parts of Ukraine, where civilians hoped — often falsely — that the label would protect their home from unwanted acts of violence or looting from the occupying force.

With pockets of Russian soldiers still thought to be hiding in basements in Sudzha, the need to clear every house means that homes are inevitably broken into, but there was no sign of the kind of wholesale looting ubiquitous in occupied Ukraine.

Stores like Russia’s famous chain supermarket Pyaterochka have been raided of produce, but computers, electronics, and other specialized equipment remain in place in offices and other shops alike.

Still, the link between the two occupations seems to have not gone unnoticed among Ukrainian soldiers: Among them, even if sentiment does lead to reciprocal action, a potent sense of revenge hangs above the Kursk operation.

Spray-painted on the front of one liquor store in Sudzha are the words “For Irpin,” and “For Okhmatdyt,” referring to the setting of some of Russia’s most blatant war crimes against Ukrainian civilians.

Before leaving Sudzha, Serhii stops the car at one last location: the house of a local policeman, where Russian soldiers had later hidden out in the first days of the incursion.

A comfortable outside courtyard shows that the family was well off, with a tractor and motorcycle standing untouched in the garage.

What was once the family’s cat sits nervously on the front steps, while chickens peck at rotting apples on the ground.

Inside, a children’s room belonging to the policeman’s son, complete with family photos and sporting trophies, is another reminder of the kind of people that once lived here: happy families perhaps, but with a patriarch actively employed as an instrument of force by a totalitarian aggressor state.

On the boy’s bed, on top of a tank-themed duvet, a remote control car controller and car lay there, their lights still blinking.

“Better not touch that,” said Serhii, wary of the threat of booby traps in places like this.

Asked if he had spoken to civilians or had any sympathy for them, Serhii shrugged indifferently.

“When we were crying out about how Russia was destroying our cities, attacking civilians with missiles,” he said, “the Russians were laughing, rejoicing.”

“I don't want to talk to them,” he added. “It's their support that made the invasion of our country possible.”

As Serhii drives back across the border into Ukraine, vehicle after vehicle speeds in the opposite direction, into Russia.

In a break away from the traditional white cross sign, the triangle shapes painted and taped by Ukrainian soldiers to identify friendly vehicles projects an understanding that this operation is not only something new, but something incredibly consequential.

The final result of the Kursk offensive, and especially the hard military achievements that hope to shake up Ukraine’s torrid defense of its eastern territory, remain to be seen.

In the meantime though, the intangible value of bringing the war deep into Russia can be felt everywhere on the ground.

“For me, what we are doing is right,” said Serhii, lighting up a cigarette as the car crossed back onto Ukrainian territory, “it motivates everyone: before this, very often when going out on missions, I didn't want to do anything, I didn't want anything.“

“Of course, we would all like to go as far as we can, you know, towards Moscow. I would really just love to stand on Red Square with our flag, that would be great.”