Editor’s note: Though the commanders quoted in this story are public figures, the other soldiers are identified by first names and callsigns only due to security reasons.

DONETSK OBLAST — In a wide field in Donetsk Oblast, the silence of what would otherwise be a sleepy August afternoon is broken up by bursts of gunfire, explosions… and laughter.

Five men enter the trench at once; two groups of two and a fifth covering the rear, as a machine gunner provides suppressing fire above their heads.

With grenades, assault rifles, and a fair share of mistakes, the men clear the trench of today’s enemy: paper targets of Russian dictator Vladimir Putin.

Here, at a training range about 25 kilometers from the Bakhmut front line, infantrymen of the Ukrainian Volunteer Army (UDA) practice assault operations in their downtime between missions.

Deputy company commander Oleksandr Bondar, 44, watches carefully from atop mounds of earth as his men go about their work.

Loud and unforgiving when one of them slips up, he breaks into an open smile after the drill is over, helping each one to climb back out of the trench.

“There can always be mistakes and problems, at the shooting range and in life,” said Bondar, “but we must watch and listen to each other, support each other, so everyone will be thinking about protecting the team.

Once finished, the soldiers each find their own way to unwind: some relax in the grass, some joke around with each other, others empty more magazines into targets on the hill opposite.

After months of hellish fighting against Russia’s assault on the city over winter and spring, Ukraine’s summer campaign around Bakhmut has been one characterized by much good news and optimism on the outside.

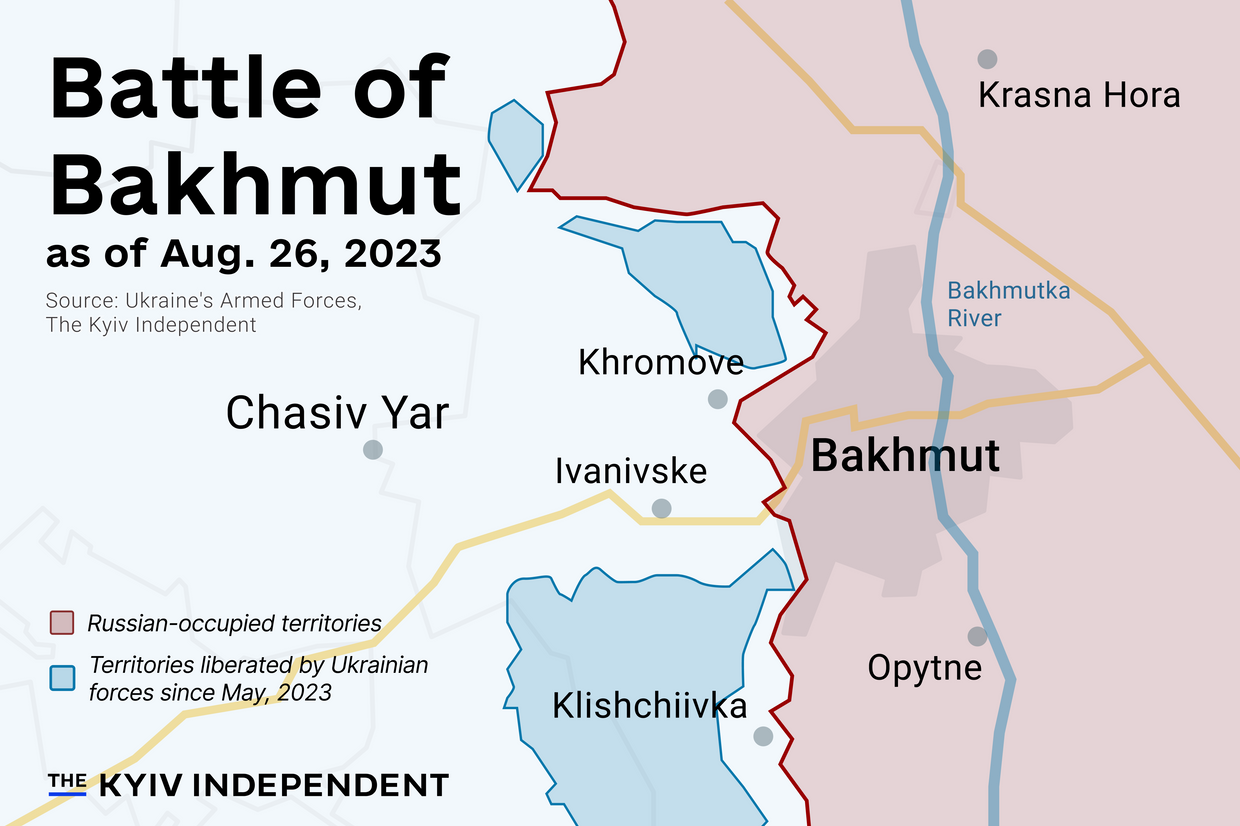

The Bakhmut area is commonly seen as one of the three main axes of the Ukrainian summer counteroffensive, along with the two main pushes on the southern front line.

While attacks in the south stalled for weeks at a time, Ukrainian forces regularly mounted successful assaults on Russian positions near Bakhmut, especially on the southern flank, where the key settlement of Klishchiivka is now contested again after falling to Russia back in winter.

“We started attacking back in May, long before the announcement of that big offensive that was talked about in the media,” said Serhii Ilnytskyi, 53, commander of the UDA grouping near Bakhmut.

Unlike on the southern front, where the counteroffensive has been spearheaded by newly-formed units who spent months training, often abroad, advances around Bakhmut are achieved by some of Ukraine’s most battle-hardened units, most of which have fought in these same sectors of the line at least since the beginning of winter.

Over mid-August, the Kyiv Independent spent two weeks in the region with infantry, artillery, medic, and drone units around Bakhmut.

For those fighting here, beneath the new-found momentum on the battlefield lies a candid and unglamorous outlook on the future of the war.

In world media, noise continues to build about whether or not the Ukrainian counteroffensive has already failed to meet its goals, and if so, who is to blame. But among soldiers here on the Bakhmut front, the word “counteroffensive” itself is treated with indifference if spoken at all.

Whether or not it is considered part of Ukaine’s great summer push, the fighting here is, in many ways, just more what it has been for a year already: assaults, counterattacks, close-quarters firefights, all under a sky teeming with drones and artillery fire from both sides.

The only difference is that now, it is Ukraine that has the initiative; but that doesn’t make things any easier.

Rather, the ongoing battles around Bakhmut give an idea of what a longer, attritional war may look like once the counteroffensive culminates, and of the increased human price Ukraine must pay to liberate every new settlement, every new trench, every new kilometer of its land.

Infantry grind

As the sun begins to set at the training ground, the UDA troops collect their weapons and head back at a relaxed pace to the awaiting vehicles, watched with endearment by their commander Ilnytskyi, resting on the bonnet of his Nissan.

Away from the cheerful chatter of the others, one young soldier stands off to the side, clearly in a more reserved mood.

“This company used to have seventy people when I joined,” said Bohdan “Hutsul,” a 22-year-old infantryman from Rakhiv in the Carpathian Mountains, looking at the group of around 25 men. “What you see here are the leftovers.”

Formed in 2015, the UDA is one of the few units of Ukraine’s armed forces that still carries a strong tradition of the many volunteer battalions that sprung up when Russia first invaded eastern Ukraine.

Eighteen months into the full-scale war however, the formation, with units fighting on all three axes of the counteroffensive, is now beginning to pay a high price for its makeup of volunteers, rather than mobilized soldiers.

“It's hard to go forward, we don't have new weapons and equipment, and these days our personnel aren't being replaced,” said Ilnytskyi.

“We move with what we have, but one thing we have is that we only accept volunteers, motivated people into our unit, who know what they are fighting for.”

South of Bakhmut, UDA infantrymen work together with Ukraine’s elite 3rd Assault and 80th Air Assault brigades, which also share the same training range. When the assault troops take a new position, the task falls on soldiers like Hutsul to move in and hold them over three-day shifts as Russian forces try to quickly take them back.

“The most important thing is to dig and entrench ourselves,” he said.

“Other guys gave their lives to take these positions, and now we have to hold them. If we don't dig in they could push us back out, and you don't want your brothers' lives to have been lost in vain.”

Blown to bits by months of heavy artillery fire, the positions they must hold often offer little cover.

“It's hard, you don't even have room to stretch out your legs, and you have to sit there for three days,” said Hutsul, who pointed to where shrapnel still remained lodged in his body after being wounded three times.

“At an earlier position we were sent for three days and it ended up being five. Thirty-six degrees, and our water ran out, thankfully on the last day it rained and we had something to drink. We held those positions, by the way, and now we are going forward.”

“Sometimes you get the impression that we have been left out to pasture, guys can complain there is not enough support,” said Bondar.

“But what they sometimes don't understand is that this is exactly our job, we are the infantry, the first line of defense, behind which the rest of the army works.”

Loosening up after the interview, Hutsul’s expression shifts back and forth from stern outward readiness to reflection, if not fear.

He has reason to be apprehensive: the following day, it is once again his turn to head out and hold the line for three days of battle.

Edge of the city

The road to Chasiv Yar, a city about 15 kilometers west of Bakhmut, is as picturesque as it is dangerous in summer. Through rolling, untended fields now overgrown with long grass, half a dozen wide dirt tracks give the endless military traffic to the city plenty of options.

Approaching the entrance to the city, a shell thuds into a field just over 100 meters away, the soil leaping into the air. Our military escort asks politely to pick up the pace.

At the unit’s headquarters in an undisclosed location in the area, multiple screens show a live drone feed of a familiar scene: the last streets of Bakhmut, ruins of a city that has been “liberated” from almost all its buildings and inhabitants.

Since Ukraine’s last great counteroffensive success in Kherson, the fighting has been dominated by the ongoing Battle of Bakhmut, a city with limited strategic value which has seen tens of thousands of casualties on both sides.

Russian forces led by the Wagner mercenary group finally took the city in late May, upon which Wagner promptly withdrew from the fight to field camps, from where it launched its brief mutiny a month later.

“It's hard to say that either attacking or defending is easier or more comfortable,” said Anton Lavryniuk, commander of the 214th OPFOR battalion, one of the last units to withdraw from Bakhmut, to the Kyiv Independent.

Though Ukraine is advancing on the flanks of Bakhmut, here on the city’s edge, it is Russian forces, reinforced by elite paratrooper units, which still attempt daily assaults of Ukrainian lines.

“When you are assaulting you have mines, you have direct contact with the enemy,” Lavryniuk said. “When you are defending you are just sitting under shelling all day, not knowing what to do but knowing your position could be assaulted at any moment and you will have to work.”

Since Ukrainian forces first regained the initiative around Bakhmut in May, Ground Forces Commander Oleksandr Syrskyi has repeatedly claimed that the occupied city was in the process of being “encircled.” On the ground, that still looks like a distant dream.

“Everyone has their own job, their own mission,” said Lavryniuk dryly. “If they (Syrskyi) say things like that then maybe they know something we don't.”

For the commander, the scenario of a drawn-out attritional war is a likely one. Already fighting in Donetsk Oblast for a year without rotation, his unit is under no illusion they will be switched out soon by fresh faces from the civilian rear.

“The idea that we will be rotated out isn't even discussed here,” he said, “it's more a subject of dark jokes more than anything, imagining we walk outside onto the street and our replacement has arrived.”

As long as that is the case, Lavryniuk is adamant that the OPFOR battalion will carry out their orders as long as required of them. “To forget everything and turn around, that is the easiest thing to do.”

Waiting out the storm

Driving out of a village near Chasiv Yar at 3 a.m., a Ukrainian military van turns off its headlights as it approaches its destination. Inside, the six passengers are silent: Even if they have done this dozens of times before, the tension of the ride out is never lost completely.

The Kyiv Independent joined a five-man artillery crew for a 24-hour shift at positions just six kilometers west of Bakhmut itself, in an area where the front line has largely stood still despite months of heavy fighting.

The chorus of both sides’ exchange of artillery fire at these positions is endless, intensifying in the afternoon to the point where the whistle of an incoming shell comes like clockwork about a minute apart. Desensitized to the sound, both soldiers and local cats are unfazed even as the blasts shake the walls of the house where they are based.

In the rare breaks in the bombardment, another sound becomes audible: Russian fixed-wing drones flying hundreds of meters above, some surveying the battlefield, and others, like the notorious Lancet kamikaze model, loitering in the air, until a target to strike is chosen.

The men operate a Soviet-built MT-12 Rapira field gun, first designed in the 1970s to fill an anti-tank function. The weapon is a relic of another era, outmatched in power, range, and accuracy by almost every other large artillery piece used in the war.

Here, however, the Rapira has found its niche. Firing from concealed positions at a range of up to eight kilometers, the weapon’s flat trajectory is ideal for targeting Russian snipers and anti-tank squads spotted working out of Bakhmut’s mangled apartment buildings.

This time, the crew’s hands are largely tied. Collecting the shells from two firing positions under cover of darkness, the shift commander Serhii “Zuba,” 30, finds that there are only 13 100mm shells left to use, with more only arriving with the shift change.

“It's always good to have some (ammunition) in reserve,” he said.

“Three days ago, the Russians assaulted and took some of our positions and we hit them with everything we had. Howitzers, mortars, we were all working together, just levelling where they were and that day we took the positions back. A good result.”

Forced to fire from close behind the front line due to the Rapira’s limitations, the crew here are especially vulnerable to Russian counterbattery fire.

Five days earlier, another shift on the same position had been targeted with poison gas munitions, leaving the crew hospitalized with internal chemical burns in their airways. Now, the team is equipped with gas masks, most of which themselves are relics from Soviet stocks.

Russia’s limited use of chemical weapons on the battlefield in Ukraine, a blatant violation of the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention to which Russia is a signatory, is one of the least-discussed of Moscow’s war crimes due to a lack of independently verifiable evidence.

Beyond the fear factor for those subject to a chemical attack, the gas is particularly deadly when coordinated with regular artillery fire, as it descends into the basements and dugouts where soldiers would normally take shelter from explosions and shrapnel at ground level.

Ultimately, though spared from a chemical attack, Zuba’s team didn’t receive any fire missions that day, as no targets were observed important enough to spend the scant reserve of shells.

As is often in war, the shift was one of endless waiting. Sprawled over couches and beds, the soldiers alternated between getting some sleep and scrolling through social media to spend the time.

Armed with a few dozen more shells, the next shift successfully eliminated a Russian anti-tank position inside Bakhmut, one artilleryman told the Kyiv Independent by voice message later.

“It will be a long slog,” said Zuba of his outlook on the war.

“It's like a wall, it (the front line) has been standing here for so long, how long we've been fighting for this f***ing Bakhmut. Sometimes our guys take some land and sometimes they take something, it's this endless pendulum going back and forth.”

Life and death

On the day Hutsul and his platoon are due to head out to battle, some of the soldiers make a short trip to a lake by their village to unwind. This is his first opportunity to swim this summer, prevented as he was earlier by his healing shrapnel wounds.

By the evening, the young soldier seems less nervous than before, his mind on the task ahead, despite annoyance at the news that he has been assigned to carry and use the cumbersome machine gun.

“I just want the war to end. If we have to sit through another winter, it will be sh*t,” Hutsul said. “One winter was enough for me; it's really cold, your feet freeze... and the bastards are assaulting you.”

“My dream... well I've never been to Crimea, I've lived in Ukraine all my life but I haven't been, it's really beautiful there. God willing, we'll go there.”

Hutsul returned from the mission with concussion from nearby shell bursts, but was otherwise unharmed. After a few days on a fluid drip, he was back on duty.

As summer draws to a close and Ukraine celebrates its second Independence Day in times of the full-scale invasion, the war itself has reached an onimous stage.

Whatever gains the southern counteroffensive makes before culmination, both sides look set for a gruelling struggle that could last for years more.

Eighteen months in, concern is mounting among soldiers, from commanders to the rank and file, that for much of the country’s civilian population, the war is increasingly fading into the distance, even as the fighting shows no signs of dying down.

“What’s annoying is that it’s the people who are not doing anything are the ones talking about fatigue,” said Ilnytskyi. “The military are fighting, volunteers are volunteering, and it’s the armchair experts and observers who are getting tired.”

“We, the military, are not tired. After the victory, that’s probably when we’ll have time for fatigue.”

On Aug. 23, it was announced that Ilnytskyi had been killed. Tributes poured in on social media for an iconic figure in the Ukrainian military, who had fought against Russia’s war from 2014, was a sitting member of Kyiv City Council, and had represented Ukraine at the Invictus Games.

“The war in Ukraine exists for everyone whether they want it to or not,” he reflected in the interview, two weeks before his death.

“For many civilians, there is no war anymore. We started running out of people a long time ago; the people who are motivated, who want to win, who understand what needs to be done. They are long gone, because they were the first to come and fight.”

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Francis Farrell, cheers for reading this article. It's been a while since I've done a field report from around Bakhmut, but this time was definitely different. For those of us who are dedicated to the victory of Ukraine, there is no point living with rose-tinted goggles on, this is what it will look like for a long time. As long as it goes on, we will be here, reporting on it as it is. Please consider supporting our reporting.