On March 29, the sanctioned Russia-flagged vessel Sv. Nikolay quietly docked at the Algerian port of Anaba near the coal terminal, waiting to be unloaded.

The metallurgical coke the ship was carrying — a key ingredient in steelmaking produced from coal — had been stolen.

The Kyiv Independent traced the vessel’s covert journey to this point — and found strong evidence that the vessel departed from the occupied Ukrainian port of Mariupol. While in Mariupol, it kept its transponder off to disguise its route.

The coal used to make the coke on the Sv. Nikolay was almost certainly mined in Donetsk or Luhansk oblasts — regions of eastern Ukraine known for their coal reserves. The territories were partially occupied by Russia in 2014 when it launched its aggression against Ukraine with the use of proxies. Moscow captured even more territory in the oblasts after the start of its full-scale invasion.

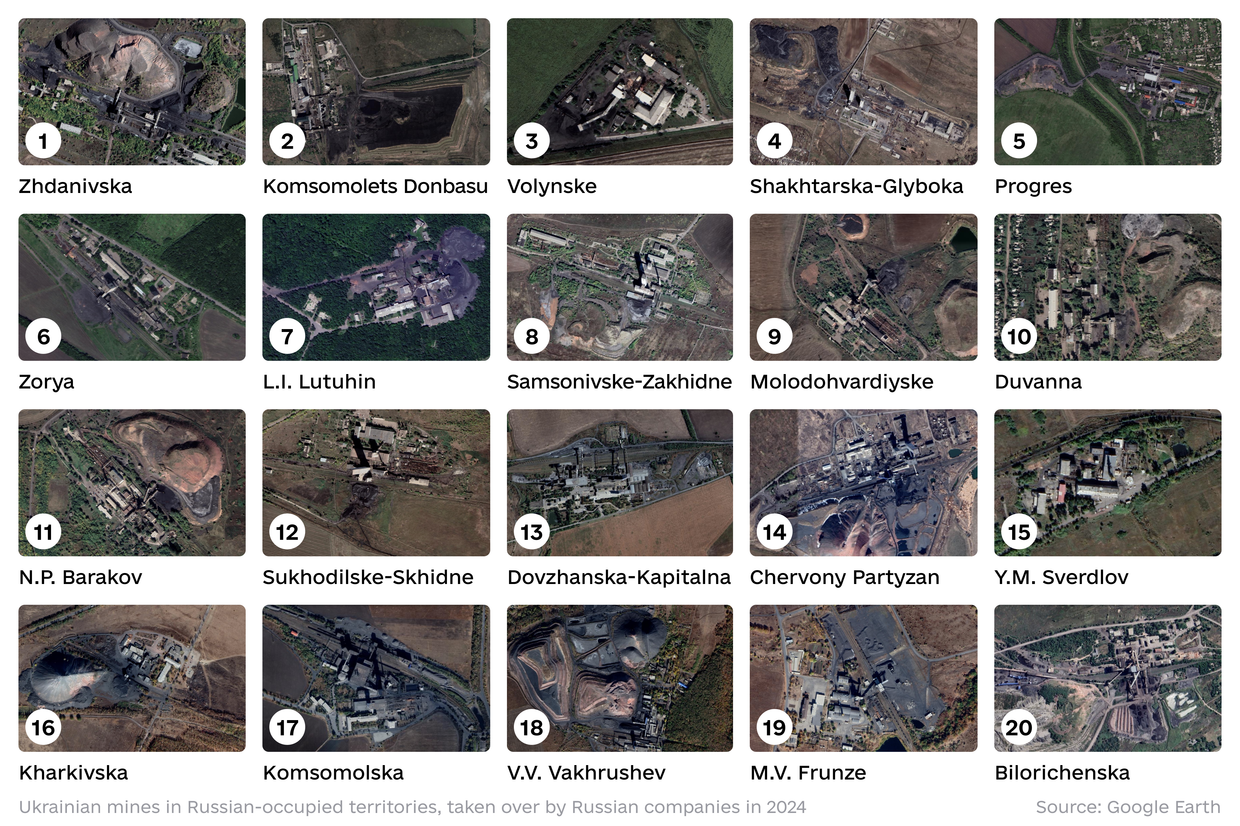

Since 2014, dozens of Ukrainian state and private-owned mines have been taken over and incorporated into the occupation economy.

In 2024, with coal mines deteriorating, the Kremlin-backed occupation authorities began handing the mines over to private Russian firms. Twenty mines have been transferred so far.

The handover process was called an “investment” model. Under the scheme, companies leased mines for several years with an option to buy them after three years. The mines, meanwhile, have legal owners in Ukraine. The scheme was similar to the resale of stolen goods.

The Kyiv Independent has identified the people behind the Russian companies profiting from the illicit lease deals, and followed the path of the stolen Ukrainian coal from Ukraine's occupied territories to international markets, where it is passed off as Russian and sold in defiance of U.S. and EU sanctions.

Familiar face among ‘new investors’

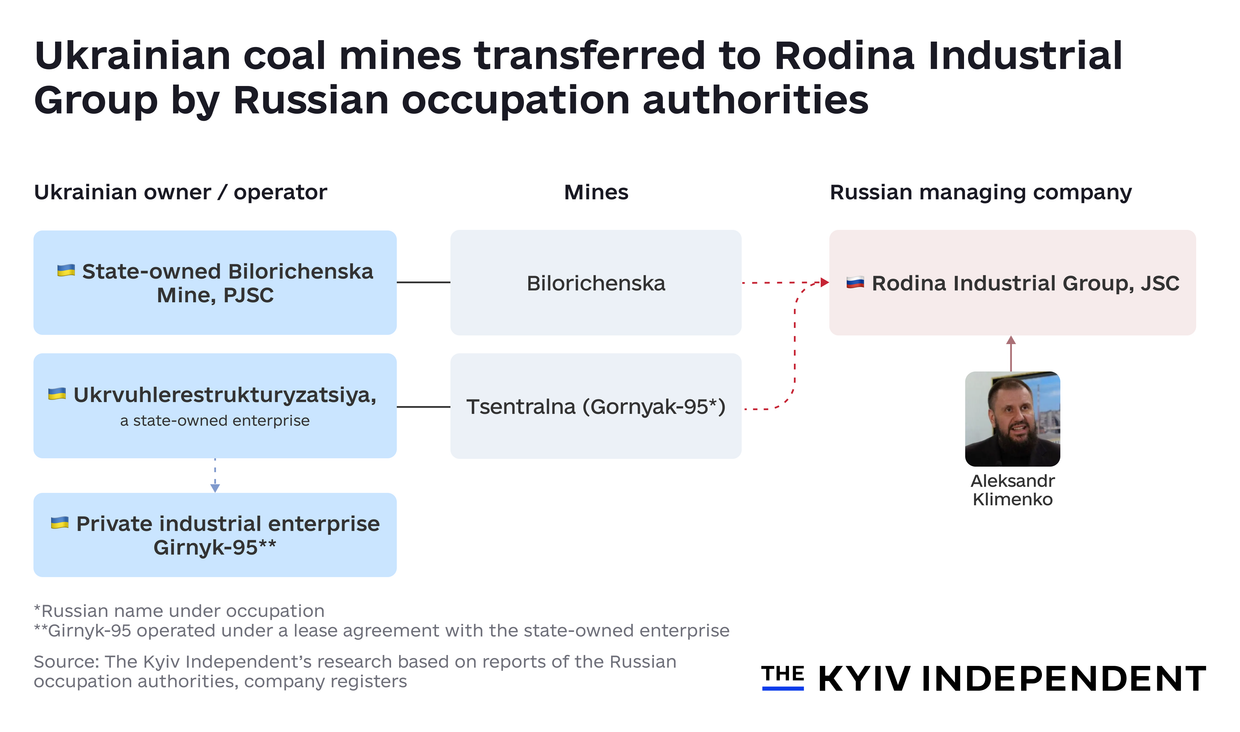

On Jan. 27, 2024, a telling scene unfolded inside a Moscow exhibition center: A Russian occupation official signed an agreement to lease the seized Bilorichenska coal mine and its adjoining enrichment plant, located near the occupied city of Luhansk, to a “private investor.”

The investor took the floor. A large, bearded man in his 40s, wearing a black suit with a black turtleneck, looked nothing but presentable. He was introduced in Russian as Aleksandr Klimenko, a shareholder in the company that had agreed to lease the mine, the Russia-based Rodina Industrial Group.

His name and face won’t ring a bell for the Russian or international public, but a Ukrainian audience might recognize the suited investor as none other than Oleksandr Klymenko — once a Ukrainian government minister working for notorious ex-president Viktor Yanukovych.

It’s been a decade since Klymenko left office and Ukraine. Like Yanukovych and the rest of his close entourage, Klymenko fled the country in the wake of the EuroMaidan Revolution in February 2014, escaping a popular uprising against Yanukovych's pro-Russian course and his government’s corruption. Like his boss, Klymenko landed in Russia.

Soon after he and the others had left, Russia captured the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea and parts of Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts.

Over the next years, Klymenko was subject to criminal proceedings in Ukraine involving corruption and treason charges. His Ukrainian citizenship was allegedly revoked in 2023.

Meanwhile, the Rodina Industrial Group was registered in Moscow in the name of Nina Klimenko, identified by the Kyiv Independent as Oleksandr Klymenko's aunt — a Ukrainian who obtained Russian citizenship. In 2022, she withdrew herself from among the founders of the company. While the current shareholders of Rodina aren’t publicly disclosed, Oleksandr Klymenko openly acknowledges control of the company.

According to the company website, back in 2020, Rodina quietly acquired another mine, Girnyk-95, located in the occupied Makiivka in Donetsk Oblast — Klymenko’s hometown.

In 2024, when Klymenko's company took over the Bilorichenska mine in Luhansk Oblast, it pledged to invest nearly $35 million over several years. Whether that promise will be kept remains unclear, but the company is already benefiting from sweeping tax breaks offered by occupation authorities to firms operating in seized areas.

Klymenko did not respond to written requests for comment.

Donskie Ugli: Putin’s Ukrainian ally granted coal mines

Another private beneficiary of seized Ukrainian mines operates much more secretively.

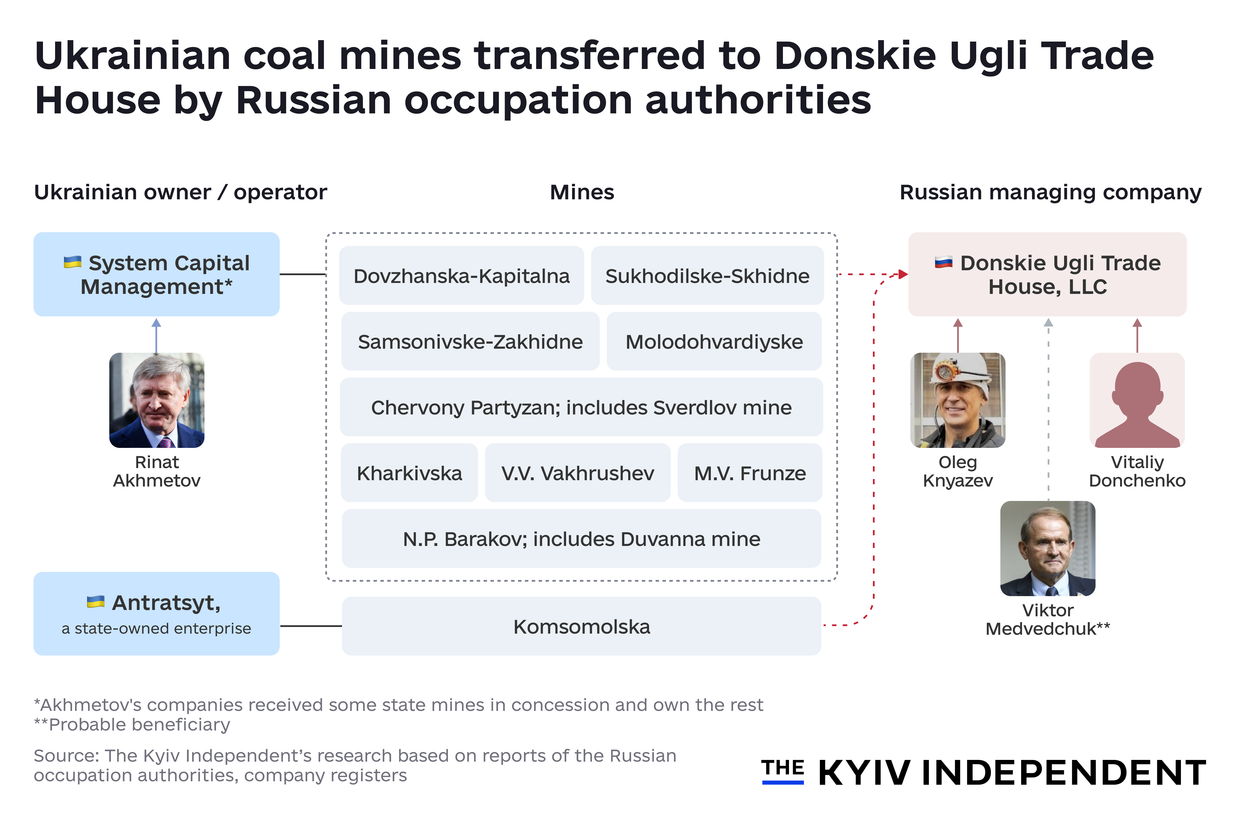

In 2024, the Russian company Donskie Ugli Trade House was granted control of as many as 10 coal mines — plus two more classified as subsidiaries — and four coal enrichment plants in the occupied part of Luhansk Oblast.

Prior to that, the company had only traded coal mined in the occupied territories, but never extracted it.

The company received five times more assets than the Rodina Industrial Group and pledged to invest 15 times more, over $540 million.

The directors and nominal owners of Donskie Ugli Trade House have changed several times over the past year, which may be a tactic to hide the real beneficiary. However, some clues remain as to who could lay such a massive claim on the occupied Ukrainian assets.

The first five mines were handed over to the Russia-based Donskie Ugli Trade House on Feb. 9, 2024. At the time, the company was led by Sergey Lisogor, a Russian citizen, who signed the lease agreement with the occupation authorities.

Lisogor is known as the business manager of Viktor Medvedchuk, a pro-Russian Ukrainian oligarch and close ally of Vladimir Putin.

Before becoming the director of Donskie Ugli Trade House, Lisogor led the Russian Investment Company Tavria-North, owned by Medvedchuk's wife. (The oligarch admitted he had registered his assets in his wife's name after U.S. sanctions were imposed on him “for undermining the national security” of Ukraine in 2014.)

According to a service that identifies how contacts are saved in people's phones, Lisogor's number was saved as "Sergey Khimpromservis," pointing to his affiliation with the Russian company. A share in Khimpromservis was also formerly controlled by Medvedchuk's wife.

When Ukraine imposed sanctions on Medvedchuk in 2021, it also sanctioned Lisogor, and two shareholders of Donskie Ugli, in the same decree.

According to Ukrainian journalists' sources in Ukraine’s National Security and Defense Council, Donskie Ugli allegedly funded several Ukrainian TV channels associated with Medvedchuk that spread pro-Russian narratives. The Ukrainian government shut the channels down a year before the start of the full-scale invasion.

Ukrainian law enforcement launched criminal investigations into the activities of Donskie Ugli. One of its shareholders, a Russian citizen, Vitaliy Donchenko, is wanted by the Security Service of Ukraine. As for Medvedchuk, he was sent to Russia in a prisoner-of-war exchange. Russia exchanged 200 Ukrainian POWs for Medvedchuk alone.

Donchenko, who’s been linked to the company since the days it was associated with Medvedchuk, still owns a 5% share in Donskie Ugli. The rest of the company is now owned by another Russian, Oleg Knyazev, who led the regional government of Russia’s Astrakhan Oblast until early 2024 and had earlier managed Russian banks.

While Knyazev is not a poor man, his income, according to the last available declaration in 2021, was millions of rubles, not dollars — not sufficient to acquire a company like Donskie Ugli. Notably, the Russian media, quoting Knyazev, identify him only as the director, not the owner of a coal company that operates the largest number of mines in the occupied territory of Ukraine, and certainly not as a potential investor of millions of dollars in seized Ukrainian mines.

The Kyiv Independent called Knyazev to ask whether he was the real owner of Donskie Ugli and whether Medvedchuk was behind the company. Knyazev said he had to clear his answers with someone first — yet didn’t say, with whom. He did not provide a response by the time of publication.

Meanwhile, Lisogor and Donchenko, both from Medvedchuk's circle, together own another company that most likely took over the management of one more seized Ukrainian mine. This time, in Donetsk Oblast.

In July 2024, a Moscow-based company, Specialist, signed an agreement to lease the Shakhtarska-Hlyboka mine and the Shakhtarska enrichment plant, according to the occupation authorities in the occupied part of Donetsk Oblast.

One of the Russian companies with this common name belongs to Lisogor and Donchenko. At the time of the transfer, the Specialist they owned was registered in Moscow. A few months later, it changed its registration address to the occupied city of Shakhtarsk, where the mine is located. The move indicates an additional source of seized minerals, presumably concentrated in Medvedchuk's hands.

The Kyiv Independent sent questions to Viktor Medvedchuk through the Russia-based Drugaya Ukraina (“A Different Ukraine”) movement affiliated with him, but did not receive a response.

Russian occupation ‘investors’

Looting coal mines in occupied Ukraine isn’t an activity enjoyed exclusively by wealthy Ukrainian fugitives. A group of Russians also gained access to Ukrainian mines.

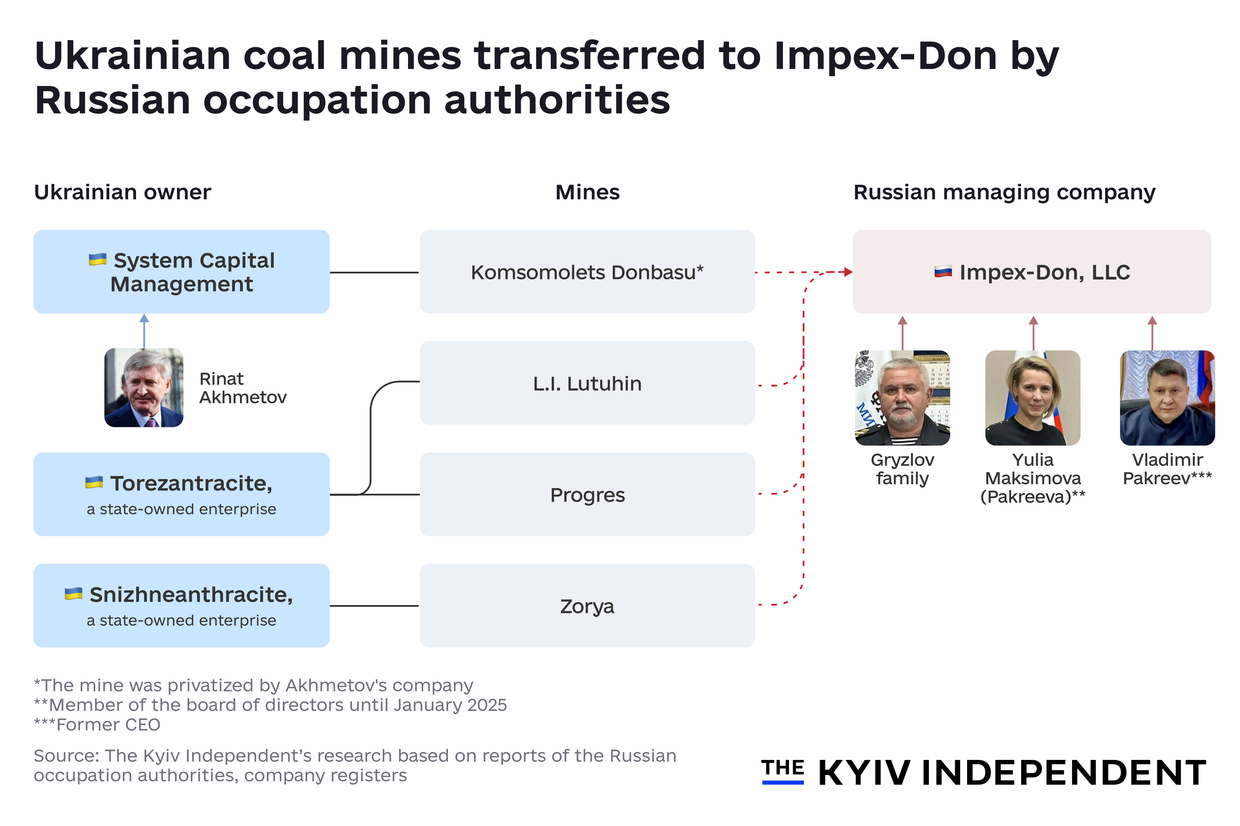

In April 2024, a Russia-based company, Impex-Don, took over four mines in Donetsk Oblast.

Impex-Don is associated with the Gryzlovs family, whose most well-known asset is the Rostov port in Russia. The Gryzlovs, a large family of two brothers, Oleg and Dmitriy, their wives, children, and other relatives, are involved in various Russian businesses, mostly in Rostov-on-Don.

As the coal mines were taken over, new faces appeared in Impex-Don. In 2024, Yulia Maksimova (Pakreeva), a Russian woman, showed up in the news as a member of the company's board of directors. (In an email response to the Kyiv Independent, Maksimova said she stepped down from this post in January 2025).

Maksimova proved to be an active participant in the Russian government's efforts to take control of the occupied Ukrainian territories, working closely with Marat Khusnullin, the Russian deputy prime minister in charge of the occupied territories of Ukraine.

Until the spring of 2024, Maksimova headed the Russian government agency RosKapStroy, with her main responsibilities concentrated in Mariupol, a Ukrainian city in Donetsk Oblast, and the largest city captured by the Russian army after the start of the full-scale invasion.

As the head of RosKapStroy, Maksimova was responsible for illegally restoring operations at the Ukrainian sea port in Mariupol under Russia’s rule. “The Mariupol port is already under control, and we’re going to be here for a long time,” Maksimova wrote on her personal Instagram page in December 2022.

The Gryzlovs also found themselves involved in the occupied seaport. In the first months of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Pavel Shvatskiy, the longtime director of the Gryzlov’s Rostov port, came to Mariupol to play the role of the Mariupol port’s director under occupation.

Later in 2023, Maksimova signed an agreement with the Rostov port, owned by the Gryzlovs, to become an element in the chain of organizing deliveries to the occupied territories of Ukraine.

After leaving the state-owned RosKapStroy, Maksimova became the Gryzlovs’ business partner. Since 2024, she has owned a 50% stake in the Gryzlovs’ private company Dimeks Si Trans renamed to RegionKapStroy, which promises to build housing for miners in the occupied Ukrainian territories.

The story of the Gryzlovs’ and Maksimova's cooperation around the occupied Ukrainian mines would be incomplete without mentioning another name: Vladimir Pakreev, a member of the occupation parliament of the Donetsk People's Republic, a Russian-controlled pseudo-state in occupied Donetsk Oblast installed by Moscow and its proxies in 2014.

A Ukrainian who has collaborated with Russia since its invasion of eastern Ukraine in 2014, Pakreev is the only one who is involved in the coal business of all the people listed in connection with Impex-Don. Back when Ukraine was in full control of Donetsk Oblast, Pakreev launched a coal mining business there.

In 2024, when Impex-Don was granted “the right” to extract coal from four seized Ukrainian mines, Pakreev became the company's CEO. In February 2025, he stepped down from this public position, but remains a partner of the Gryzlovs in a Russian firm with a similar name, Trading House Impex-Don.

According to Maksimova's comments to the Kyiv Independent, Pakreev was not a co-owner of the main Impex-Don entity, but only negotiated on its behalf and held a power of attorney.

A detail that may explain Pakreev's appearance in business connected to the Gryzlovs and Maksimova, is that in 2024, Maksimova got married. She neither disclosed her husband's name publicly, nor showed a photo of him, but there is no doubt that his surname is Pakreev, as she changed her maiden name to Pakreeva. Maksimova refused to answer the question whether she had married Vladimir Pakreev.

Having promised to invest the equivalent of $175 million in the seized mines over five years, Impex-Don soon received financial support from the occupation government in the Russia-controlled part of Donetsk Oblast. It allocated the equivalent of nearly $2 million to the private company for the purchase of mining equipment.

The company didn’t respond to a written request.

Impex-Don became the second largest beneficiary of the seized Ukrainian mines, after Donskie Ugli Trade House, pushing the Rodina Industrial Group to third place.

These three are not the only ones who have been given the opportunity to mine seized coal. For more details, see the chart.

The route of stolen coal to the global market

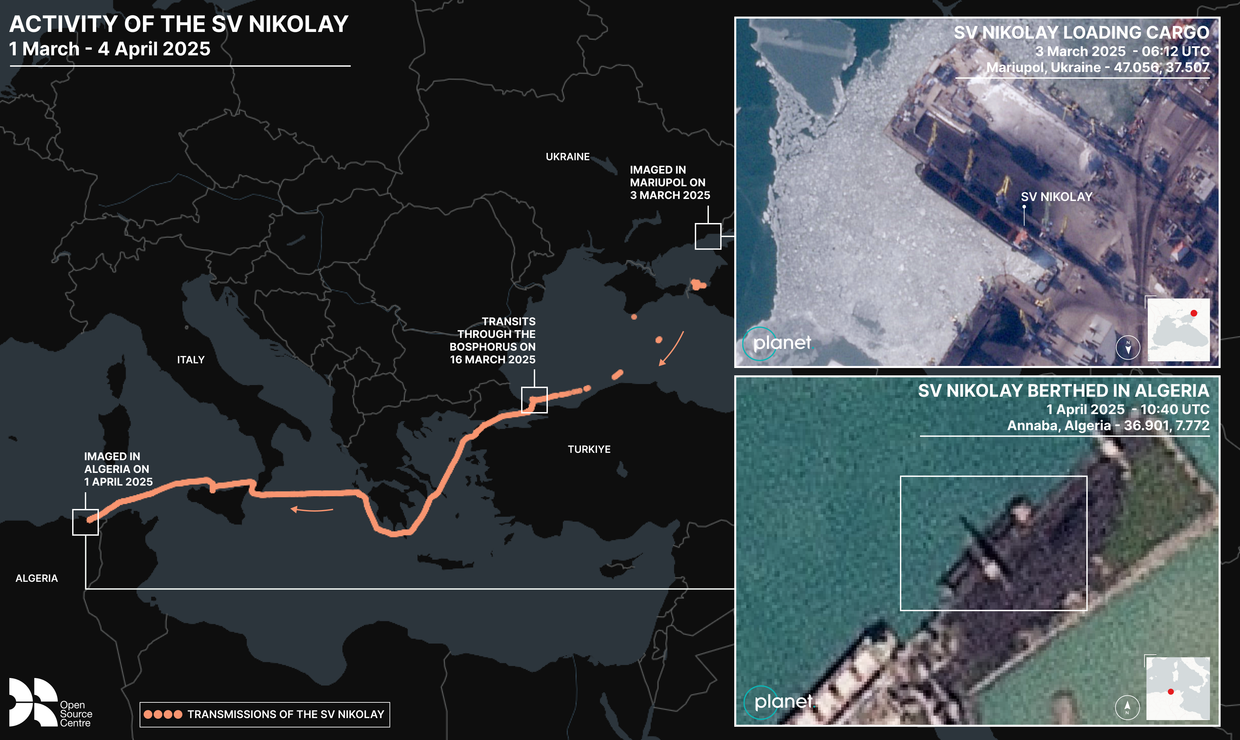

The Russian-flagged vessel Sv. Nikolay, which is sanctioned by the U.S., loaded the metallurgical coke in the Russia-occupied seaport of Mariupol on March 3, 2025, according to the documents submitted by the Russian ship's crew and seen by the Kyiv Independent.

The leaked documents indicate that the ship then headed to the Russian port of Temryuk and set off on a further journey abroad after spending a week in the Temryuk port.

The Kyiv Independent verified the vessel’s route using satellite imagery and several ship tracking services, as well as by consulting with experts who track vessels.

Although the destination of the coke was Turkey, according to the leaked documents, the vessel did not unload in the Turkish port, but spent several days at anchor. On March 29, the Sv. Nikolay finally arrived at a coal terminal in Annaba, Algeria.

The U.K.-based Open Source Center, which produces open-source global security research, visualized the vessel's route based on its AIS data and satellite imagery.

The difficulty was that the vessel didn’t broadcast its position at the time it was in Mariupol, according to the leaked documents.

However, satellite imagery of the Mariupol port, captured on March 3, 2025, shows a vessel with its three cargo bays open, possibly loading coke at the terminal.

“The vessel matches the length and physical features of the Sv. Nikolay and is highly likely the vessel in question,” concluded Hamish Macdonald, senior analyst at Open Source Center.

The bulker’s dark period may signal an attempt to hide its activity in a particular location, as calling at the occupied Ukrainian port is a violation of Ukraine’s border.

“Shipping coal taken from occupied Ukrainian territory for sale on the global market is not something that the operators of this vessel would likely want to advertise,” adds Macdonald. “If they are trying to obfuscate the true origin of the coal, then broadcasting its movements in Ukrainian waters and ports would be counterintuitive."

The visit to the Russian port of Temryuk before moving further could have been needed to conceal the origin of the coke, said Kateryna Yaresko, a journalist with the Ukrainian SeaKrime project run by the Myrotvoterts Center that tracks Russia’s illegal shipping activity.

“In the port of Temryuk, they reissued the documents without cargo operations, meaning they issued a new cargo declaration stating that the coke was loaded in Temryuk,” says Yaresko who analyzed the leaked documents.

Indeed, the papers contain two different cargo declarations for the exact same coke shipment onto the same vessel, loaded in the occupied port of Mariupol and in the Russian port of Temryuk a week later.

Yaresko is confident the second declaration is fake, as the ship was already loaded when it arrived at the port of Temryuk. “They deliberately enter a Russian port to counterfeit documents,” she says.

Green Rabbit Limited is listed in the documents as the shipper of the coke. A company with this name is registered in Hong Kong, not by locals, but by a Russian citizen.

It has already been caught exporting coal, coke, and grain from the occupied Ukrainian territories. In early 2024, the Russian investigative publication iStories revealed that Green Rabbit was owned by Muslim Temerkayev, an adviser to the father of Alina Kabayeva. She is widely thought to be Vladimir Putin’s partner and the mother of his children.

According to the company’s annual report submitted after iStories investigation was published, Green Rabbit changed its shareholder to a different, lesser-known man, Andrey Rashchupkin. The Kyiv Independent identified him as a native of the Ukrainian city of Donetsk who obtained Russian citizenship.

The Kyiv Independent reached Andrey Rashchupkin by phone. When asked how he had become the owner of Green Rabbit, he hung up without a word.

Green Rabbit did not stop trading stolen Ukrainian resources after the change in shareholder. The leaked 2024 customs records indicate it repeatedly bought coal from Donskie Ugli Trade House, the largest operator of seized Ukrainian mines allegedly linked to Medvedchuk, and delivered it to Turkey.

The available customs data is not complete and may not reflect all Green Rabbit suppliers; however, it shows that Impex-Don also sold coal through Green Rabbit in 2023.

The route from Mariupol through Temryuk and further outside Russia, which the Sv. Nikolay followed at the request of Green Rabbit, is one of the ways stolen Ukrainian coal and coal products gets to international markets.

Russian companies that gained access to the seized Ukrainian mines didn’t hide their plans to sell some of the coal outside the occupied territories and Russia.

“Rodina and Donskie Ugli (...) are negotiating coal shipments to Turkey,” the Rodina Industrial Group announced on its website in August 2024. According to customs data, Donskie Ugli Trade House was already trading coal with Turkey at that time.

A little later, Donskie Ugli Trade House added they were also negotiating with buyers from China, India, Iran, Uzbekistan, and Malaysia. The occupation authorities confirmed that Donskie Ugli was going to export coal through the occupied port in Mariupol. Other export options were also being worked out: through the Russian ports of Taganrog and Rostov-on-Don, and by rail through Azerbaijan and Iran, according to a source of the Russian media outlet RBC.

Yulia Maksimova (Pakreeva) of Impex-Don also confirmed to the Kyiv Independent that the company had started exporting the seized Ukrainian coal, but declined to provide further details.

Russian mining companies do not always sell illegally mined Ukrainian coal directly to foreign buyers such as Green Rabbit.

Russian intermediaries, like the Russian fuel trading company Energoresurs, appear in the chain between mining companies and foreign buyers. According to iStories, Energoresurs exported the largest amount of seized Ukrainian coal abroad over the past two years, mainly to Turkey.

Its registered owner, according to the publication, plays a nominal role, and the real beneficiary appears to be Oleksandr Yanukovych, the son of the fugitive ex-president of Ukraine.

Energoresurs buys coal from mining companies, including the largest private operators of the seized Ukrainian mines, Donskie Ugli Trade House and Impex-Don, and transports it to Turkey by rail or sea.

Reduced appetites: ‘Investors’ seek to return mines to the occupation authorities

Currently, a quiet but significant drama is playing out. Two of the largest private recipients of mines in the occupation have begun to close some of them and are trying to return them to the occupation authorities. The process is not public.

The first private reports appeared in mining groups on Russian social media in the spring of 2025. Since March, local residents have been discussing the shutdown and closure of mines that were transferred to private hands a year ago.

The Kyiv Independent found references to the closure of three mines operated by Donskie Ugli and two mines by Impex-Don. Miners discussed these among themselves, and the companies never commented on the discussion.

When asked by the Kyiv Independent about the reasons for the closure of two Impex-Don mines, Yulia Maksimova, the company's former top manager, replied: “There were some good technical reasons.”

The Russian media outlet RBC reported, citing its own sources that Donskiye Ugli is actually abandoning seven out of the 10 mines it runs. The issue was discussed privately at the level of the Russian Energy Ministry on April 10, the publication says.

The reasons cited include low coal prices globally and high maintenance costs. This does not mean that all the mines that have gone into private hands will be closed. Each of these groups still holds some of the seized Ukrainian assets.

Meanwhile, Russian ships continue to export stolen Ukrainian resources. According to a Kyiv Independent source, on April 21, the Alpha Helios vessel, loaded with metallurgical coke, again shipped by the Hong Kong-based company Green Rabbit, entered the Russian port of Temryuk from the occupied Mariupol to continue its journey to Algeria.

Note from the author:

Hey, this is Alisa Yurchenko, the author of this story. As you may know, it is a deadly risk for Ukrainian journalists to visit Russia-occupied territories to report. A Ukrainian journalist Viktoria Roshchyna paid with her life for a trip to the occupied territory — the Russians illegally imprisoned and tortured her; she died in captivity at the age of 27.

This is why this investigation had to be written from Kyiv. But I used every tool and opportunity to collect all the possible information. It is extremely important for Ukrainians to shed light on what is happening in the occupied territories, even though we can’t access them. If you want to support such investigative work, become a member of the Kyiv Independent. Your contributions go directly towards our journalism.