There’s nothing sweeter than home, unless you’re a Kyivan — because then you have Kyiv Cake.

While many foreigners associate the city with the butter-filled chicken cutlet known as Chicken Kyiv, which is likely of French origin, the layers of nutty meringue and buttercream coated with crushed hazelnuts that make up Kyiv Cake originated in the nation’s capital.

The lore surrounding the invention of Kyiv Cake in 1956 is almost as legendary as the factory where it’s made. In all versions of the tale, the capital’s most well-known and loved dessert was invented in a factory that opened 70 years earlier, in 1886.

What started as Valentin Efimov’s “steam factory for the production of chocolates and candies” in the 19th century would go on to make confections so popular that they outlasted three forms of government — the Russian Empire, Ukrainian People’s Republic, and finally, the Soviet Union.

During its 137 years in operation, the factory has found its way into many key moments of Kyiv’s history — from its workers resisting Hitler to becoming entangled in a trade alliance that led to the EuroMaidan Revolution in 2013.

From Valentin Efimov to Karl Marx

In the early 1880s, Demiivka was a sleepy suburb, approximately eight kilometers southwest of downtown Kyiv with just 24 houses and a sugar refinery.

That was enough for Valentin Efimov. In 1886, he established the “steam factory for the production of chocolate and candies.” Soon after, 200 employees turned out 200 tons of chocolates, caramels, jams, and pastilles per year.

Thirty years later during the Bolshevik Revolution, Efimov’s steam factory was seized by the state. On May 5, 1923, it was renamed the Karl Marx Confectionary Factory in honor of Marx’s 105th birthday.

To supply growing demand across the USSR, the facility expanded into the sugar refinery that brought it to Demiivka in the first place. The factory employed 3,400 people in 1940 making it one of the largest enterprises in Soviet Ukraine.

Those same workers bravely resisted Hitler's invasion during the first Battle of Kyiv in 1941, but the factory was later destroyed. It was reconstructed in 1944 with increased capacity.

In 1955, Soviet leader Nikita Krushchev exchanged visits with Indian Prime Minister Jawaharhal Nehru to initiate deeper trade ties with the country. As a result, the Soviet Union purchased huge amounts of cashews from India. Confectionary factories across the USSR were tasked with finding a way to use this novel nut.

How Kyiv Cake started with a cover-up

Legend has it that Kyiv Cake was invented by accident and that the first cake was an act of solidarity among coworkers.

The story goes that at 17, when Nadezhda Chernogor was rejected from medical university, she got a job at the Karl Marx Confectionary Factory. Her first six months were marked by crumbling cakes and melted frosting.

Then, according to folklore among factory workers, one evening in 1956 someone forgot to refrigerate the meringue at the end of their shift. The next morning the department’s manager, Konstantin Petrenko, and Chernogor, found large amounts of seemingly wasted meringue.

The two brainstormed ways to cover up the mistake and salvage the ingredients. Supposedly, this is when they first sprinkled meringue with vanilla powder and cashew pieces, smothering three hard disk layers with buttercream and finishing it off by adding a floral design on top.

But if you had asked the Communist Party, Kyiv Cake was no mistake. According to the official patent from 1973, the factory was working to develop unique cake recipes for years before two factory workers, Anna Kurilo and Galina Fastovets-Kalinovskaya, invented Kyiv Cake in 1956.

Over 65 years of celebrating

Kyiv Cake was an instant hit all across the Soviet Union. The cakes were popular for holidays, given as gifts, and sent to friends and family outside the city. People recall stories of lining up at 4 a.m. in the Ukrainian capital for the opportunity to buy one.

In the early years, every Kyiv Cake was filled with cashew pieces and a cross between French and Russian buttercreams made from egg yolks, butter, and sweetened condensed milk. Cakes were then hand-decorated with varying floral designs, unique to each factory decorator.

Over time, some of the cake’s original features proved hard to scale. With the price of cashews on the rise in the 1960s, they were replaced with hazelnuts. The original raw-yolk buttercream did not travel well and was replaced with a more stable oil-based buttercream.

As the cake’s popularity grew, the factory became increasingly worried about fakes. The chestnut has been an informal symbol of Kyiv since the late 19th century. So by 1965, every Kyiv Cake was topped with chestnut flowers and packaged in a round box covered in chestnut leaves. In 1969, the City of Kyiv debuted a new coat of arms that also prominently featured chestnut leaves, reinforcing the connection between the city and its famous cake.

At Leonid Brezhnev’s 70th birthday celebration in 1976, Ukraine gifted the Soviet leader an oversized Kyiv Cake with 70 layers, weighing five kilograms. Attendees said that Brezhnev liked it so much he tried to have his chefs replicate the recipe.

In the 1990s, trains between Kyiv and Moscow were nicknamed “Cake Carriers” because of the huge volume of Kyiv Cakes departing from Kyiv’s railway station. Passengers would arrive early to negotiate with the conductor, hoping to get a coveted spot for their cakes in the refrigerator of the dining car.

The contemporary reign of the ‘Chocolate King’

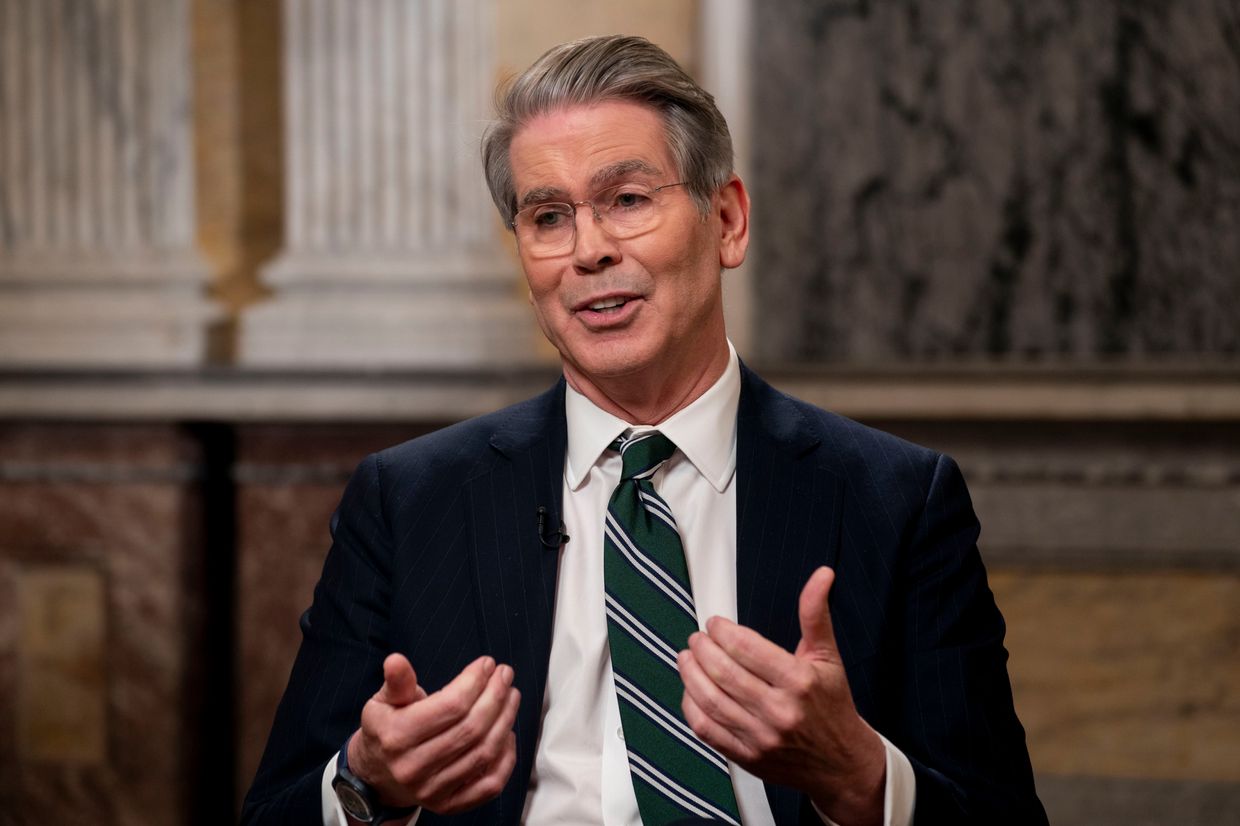

Petro Poroshenko, Ukraine’s president from 2014 to 2019, acquired control over the Karl Marx Confectionary Factory for an undisclosed sum soon after its privatization in 1996. The new company was called Roshen, a derivation of the owner’s last name, Po(Roshen)ko. In time, he would also become known as the “Chocolate King.”

Between 1998 and 2012 the number of products made by the factory in Kyiv increased fivefold. The Roshen Corporation also broadened its reach, selling 350 products in 35 countries across Europe, North America, and Asia.

By 2013, Roshen products represented roughly a quarter of all confections sold in Ukraine. The company also held five percent of the Russian confections market which made up roughly 40% of Roshen’s sales.

In the summer of that same year, Ukraine and Moldova were making preparations to sign the European Union Association Agreements at a summit in November in Vilnius, Lithuania. Meanwhile, Russia was looking for ways to pressure Ukraine into joining the Russian Customs Union.

Poroshenko had publicly supported Ukraine’s alignment with the European Union, saying “Our opportunity to sign an association agreement with the European Union is just the gate of possibilities, and (it happens) once in several decades.”

Russia had a well-documented history of banning imports of consumer goods as a coercive trade tactic. Georgian wine and “Borjomi” mineral water, Ukrainian cheese, Moldovan wine, and Lithuanian dairy products were all subject to this treatment.

Keeping with the trend, on July 29, 2013, Rosspozhivchnadzor, or the Russian agency for the protection of consumer rights, issued a ban on the import of Roshen products. The agency claimed that products produced in Ukrainian facilities were using outdated requirements for permissible levels of yeast. Further, they cited that the key supplier of milk powder for Roshen’s products was not listed on the register of permissible suppliers for the Russian market.

When relevant authorities in Belarus, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Moldova performed unscheduled inspections of the Roshen products in question, no violations were found. Production at what was still known as the Karl Marx Confectionary Factory fell by 14%.

Then just weeks before the summit in Vilnius, former President Yanukovych refused to sign the agreement with the European Union, sparking the protests that led to the EuroMaidan Revolution.

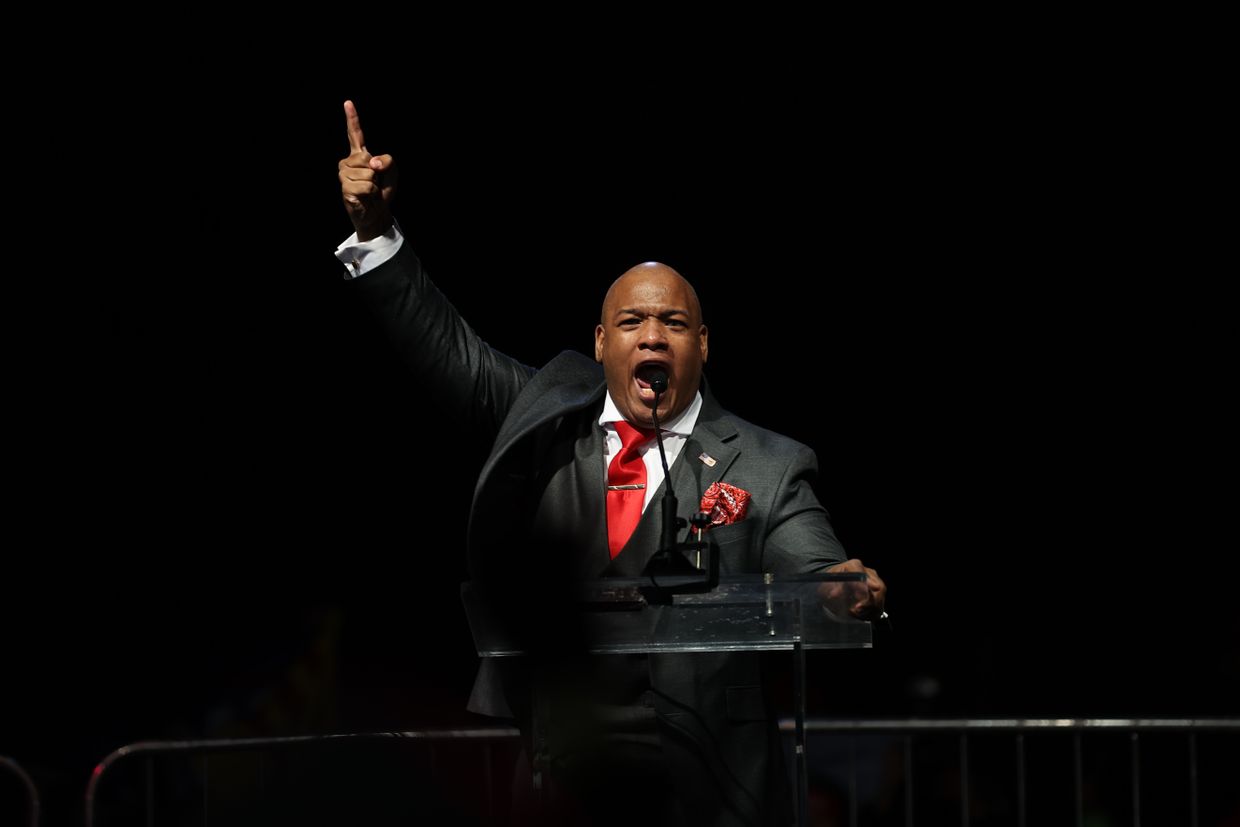

The Chocolate King supported the protestors of Maidan financially, keeping his distance from political debates with the revolution's leaders. Poroshenko became president in a snap election in 2014. Yet the monument to Karl Marx stood in front of his factory in Kyiv until 2016.

It took another two years to officially change the name from Karl Marx to Kyiv Roshen Confectionary Factory.

Kyiv Cake, Near and Far

Today the five-story high and several city block-wide complex known as Kyiv Roshen Confectionary Factory sits near the Demiivka metro stop in southwest Kyiv, the headquarters for one of the world’s top 30 candy companies.

The waft of warm chocolate precedes the 200,000 decorative lights illuminating Roshen Plaza, a popular entertainment complex with year-round light shows and seasonal activities including an outdoor ice skating rink and summer fountain displays.

Inside, 800 employees make Kyiv Cake, cookies, pastries, and a popular hazelnut-filled chocolate called “Evening Kyiv.” Plumes of smoke billow out of an orange and brown striped stack that doubles as an homage to the original 19th-century building.

Outside the factory, Ukrainian chefs around the world are crafting their own versions of Kyiv Cake.

In Kyiv, the Milk Bar restaurant group makes a version with almond meringue called “My Kyiv Cake.” The newly opened Ukrainian restaurant Anelya in Chicago includes gianduja, a chocolate hazelnut paste, in their recipe.

Meanwhile, Anna Voloshyna, author of BUDMO! Recipes from a Ukrainian Kitchen, hosted an online Kyiv Cake class as a part of her ongoing fundraising efforts for an ambulance that will be sent to Kharkiv to help the International Aid Legion.

Yulia Bevzenko’s 2018 project “Shukai!” (meaning “Search!” in Ukrainian) installed over 40 miniature bronze sculptures of Kyiv’s most famous symbols around the city for tourists to find.

Mounted at the entrance of the Kyiv Roshen Confectionary Factory stands a tiny monument to the cake that made it famous.