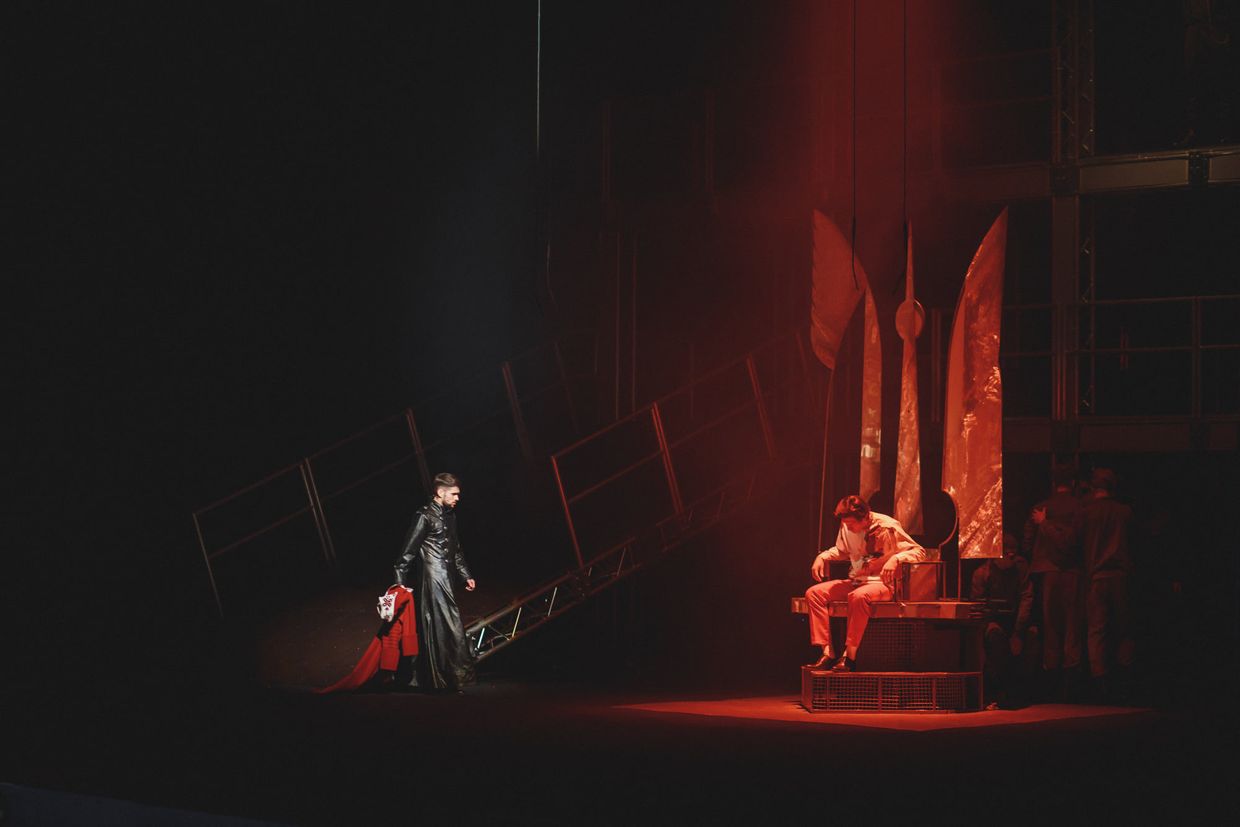

I know the exact moment when Russian President Vladimir Putin decided to launch his full-scale invasion of Ukraine: Oct. 1, 2021. It was the day the opera "Vyshyvanyi: The King of Ukraine" premiered in Kharkiv. I was at the event and vividly recall all the details.

The premiere proved to be a cultural shock for Kharkiv and resonated across Ukraine. The air filled with premonition, a sense that something monumental was about to unfold, though no one could articulate it precisely. Words swirled on the tip of the tongue; they were tender yet pregnant with meaning, like champagne bubbles teasing the palate at a post-performance reception.

As we would soon discover, these words heralded the end of an era and the onset of a great war. Beyond the walls of the enchanting castle, where refined society had gathered for a festive ball, the overture of a terrifying storm was unfolding.

What made this event extraordinary? Firstly, the protagonist’s persona: Wilhelm von Habsburg, a descendant of the Austrian throne, known in Ukrainian history as Vasyl Vyshyvanyi. While quite well-known among intellectual circles in Ukraine, his popularity and fame as a one-time contender for the Ukrainian throne are largely confined to specific regions due to obvious historical reasons.

In other words, if an opera about Vyshyvanyi were staged in Lviv, it would surprise far fewer people. Even in Kyiv, it would prompt a bewildered raise of the eyebrow and a few clarifying questions (despite Vyshyvanyi’s connection to Kyiv: it was here, in Lukianivska prison, that the archduke’s life was cut short after he had endured abuse by the Soviet secret services).

Yet, the opera about Vyshyvanyi in Kharkiv was something completely alien. It was shocking to hear a story about a descendant of the Austro-Hungarian throne, a Ukrainian patriot who fought for the Ukrainian People’s Republic, and a publicly gay figure in Kharkiv.

Equally shocking was the modernist, complex music composed for the opera by contemporary Ukrainian composer Alla Zahaykevych. The opera was directed by, perhaps, Ukraine’s finest director, Rostyslav Derzhypilsky, with the libretto penned by Serhiy Zhadan.

Picture this audacious, even defiant opera staged in an unattractive Soviet-era theater building. It felt as though massive, unseen tectonic plates were colliding and grinding beneath the surface, striving to align and form a new structure, a new foundation. Perhaps this is reminiscent of how modernist art was perceived in the atmosphere of bourgeois Vienna (did anyone then realize that the collision of these two realities would lead to World War II?)

Another crucial aspect to consider is the financial backing behind the production. The opera was financed by Vsevolod Kozhemiako, a prominent businessman who is listed in Forbes and hails from Kharkiv. His wife, Oleksandra Sayenko, served as the driving force behind the entire project. It’s noteworthy that following the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Vsevolod emerged as the wealthiest Ukrainian to enlist in the Defense Forces. Eventually, he founded and led the entire combat brigade known as “Khartia” (which, according to one interpretation, stands for Kharkiv + art + i ia (in Ukrainian, “and I”)).

In 2022, there were plans to tour this opera abroad. Even then, there was an understanding that while in the east we were fighting for our independence in the trenches, in the west we needed to reclaim our sovereignty through university classrooms and theater boxes.

Now, with all this information in hand, let’s take a panoramic view of this extraordinary event. Picture a high-profile cultural gathering dedicated to a remarkably unconventional historical figure: a pure Habsburg, an impassioned Ukrainian, and an openly gay individual. All of this unfolding in Kharkiv, a city situated on the Russian border, once touted as the “first capital” by the Bolsheviks in the occupied part of Ukraine a century ago; Kharkiv, which, throughout the 30 years of Ukrainian independence, predominantly supported pro-Russian parties; a city tarnished by the signing of the so-called Kharkiv Pact between Yanukovych and Medvedev, a move that facilitated the insidious encroachment of Ukraine from within.

The production was made possible by private funding, yet the opera took place in a state theater, serving as an example of a public-private partnership. In other words, in its 30th year of independence, Ukraine has finally matured enough to allow new, honest, non-oligarchic Ukrainian businesses to finance significant cultural events in collaboration with the state, transcending traditional templates and expectations.

It is important to note that staging an opera from scratch is not akin to something like creating a poem. It is no wonder opera was considered an imperial art: it involves numerous individuals, processes, talent, resources, and institutional capacity that only stable and affluent structures could manage.

One can almost envision this scenario within the walls of the Kremlin, perhaps even in the form of a comic book: Putin, seated at his desk, confronted by a large poster advertising the Vyshyvanyi opera in Kharkiv. His expression contorted with rage, a vein pulsating on his temple, teeth grinding in frustration. How could this be? We disposed of him, “we’ll wipe him out in the shithouse,” and yet here he returns to Kharkiv! This state must be eradicated, for its most hostile tendencies have encroached upon the Russian border, threatening to engulf and overwhelm us!

Of course, this depiction is purely metaphorical and a product of artistic imagination. However, within it lies a rational kernel: an event of such magnitude, quality, and expressive power was obviously not justification for invasion. Symbolically, it underscored how Ukraine had transformed over 30 years—growing stronger, wealthier, more developed, and modern—on its journey toward embracing the European idea throughout the country.

My train journey from Uzhhorod to Kharkiv lasted over a day, a staggering 26 hours spent in a sleeper car, gazing out the window, engrossed in a voluminous book, and occasionally drifting off to sleep. This route is one of the longest direct railroad lines in the country, bridging the far west and northeast of Ukraine. In February and March 2022, tens of thousands of Kharkiv residents relied on this route to flee the city amid the chaos of war, seeking refuge in safer regions. The 26-hour train ride serves as a poignant illustration of Ukraine's vastness, while the leisurely pace of the railroad mirrors the gradual movement of ideas and the pace of reforms in our independent state.

“Border, Belgorod, Russia! Leaving now!” – this resounding cry greeted me in front of the station square in Kharkiv on Oct. 1, 2021. It was heartening to see no queue of newcomers awaiting this call. Yet, it was equally surprising to realize that on this very morning, I had arrived at a region bordering Russia to immerse myself in a Central European context – that Friday marked the premiere of the opera “Vyshyvanyi: The King of Ukraine” in Kharkiv. The title itself encapsulated a dialogue of two contexts: ‘Vyshyvanyi’ (“embroidered” in Ukrainian) symbolizing traditional Ukrainian realities, and ‘King of Ukraine’ representing our European aspirations—a dream of a royalist European scenario amid the tumult of Ukrainian history.

Thus, right from the doorstep, Kharkiv was met with reminders of its proximity to Russia, urging and inviting people to seize the unique opportunity to cross over to Belgorod, from where missiles and shells would rain down on Kharkiv just months later. However, few were inclined to board this “minibus,” as economic and trade ties had long dwindled, and Russia's technological stagnation offered no prospects for an optimistic future.

Something old died, and something new began to stir in Kharkiv and eastern Ukraine as a whole. This new phenomenon heralded the emergence of Central Europe – a practice of Central Europeanism spanning various facets of life. From everyday routines intertwined with European supply logistics and quality standards to the cultivation of a fresh civic dignity and rights consciousness within a democratic framework, alongside a distinct sense of geopolitical solidarity advocating caution toward large and powerful entities such as empires, all contributed to this transformative shift.

It can be argued that in the 30th year of independence, a new concept of Central Europe was born in eastern Ukraine and eastern Europe, just as it slumbered on the historical territories flanking the eastern reaches of the European Union. These weren’t mutually exclusive, antagonistic notions; rather, after protracted and exhaustive debates on Central Europe, we overlooked its fundamental attributes – mobility, dynamism, and, in a positive sense, contagiousness. While we once believed Central Europe to be eternally fixed, it gradually advanced eastward, akin to an aged train.

Our primary misjudgment lay in a geographical misconception: the assumption that Central Europe was confined to the conventional boundaries of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Here, “small nations” harbored a pervasive fear of their neighbors, cloaked in a poignant poetic melancholy set to the graceful strains of the Viennese waltz. Despite their tumultuous histories and occasional outbreaks of animosity, these nations shared profound cultural bonds, culinary traditions, and, as one writer eloquently observed, the similar look of their train stations.

What is more, their mentalities, political legacies, and systemic challenges on the path to Westernization mirrored one another. In essence, Central Europe was a locked concept that was simplistically put on a geographical map in the form of the old boundaries of the impotent Visegrad Four.

The mistake in many years of discussions lay in confining the concept, forgetting that ideas know no borders and can freely traverse, infecting more adherents along the way. This was evident, for instance, in Slovenia and, even more so, in Croatia, which sought to shed the disliked Balkan stereotype and embraced their Central European identity. Likewise, this concept proved to be a lifeline for Romania, seeking refuge from the East in a more prestigious and European club.

Similarly, this idea found its way to Ukraine. Initially, it found footing in the geographically and historically confined territory of the former Austro-Hungarian regions, terminating at the Zbruch River. However, it later permeated numerous minds and hearts, extending to Kyiv and central Ukraine during the Orange Revolution, and eventually reaching the eastern borders. Of course, many adherents of this idea may not explicitly identify as supporters of Central Europe, as it’s the essence rather than the label that matters. So, what defines the essence of Central Europe, and how has it undergone a revival, especially in the wake of the predatory Russian invasion.

The potency of this idea is most evident when it is projected toward the future rather than dwelling on the past. Indeed, when we scrutinize history and cherry-pick facts to bolster our arguments, Central Europe may appear barren, irrelevant, stagnant, and dead. For how else can we justify the relevance of the Austro-Hungarian legacy today?

The majority of the nations once under the Habsburg crown are now members of the European Union – a pinnacle of unification unparalleled in the continent’s history. The EU surpasses the “golden age” of imperial Austria and its most benevolent emperor in terms of democracy, human rights, prosperity, and economic development. Central European states now partake in political, security, and economic unions, affording them a sense of relaxation and detachment from global concerns. Furthermore, they bear their own scars and traumas, which often translate into assertions, ostentatious discontent, and demands directed at others.

The situation changes dramatically when we shift our focus from the past to the future. It is the trajectory towards the future that imbues the idea of Central Europe with its life-sustaining, vitalistic significance and vigor.

Before the outbreak of World War II, this idea was anxiously born, evolving into a dream of a confederation of “small nations” united in their ability to collectively resist the pressures exerted by great hegemonic powers and occupiers. Preceding World War II, Central Europe found itself sandwiched between the formidable German Reich and the Soviet Union, and it was the shared experience of perennial threats that shaped the political aspirations of its leading figures, resulting in both commendable and calamitous decisions.

Following World War II, Central Europe underwent a transformation into a hybrid Warsaw Pact. And it was this forward-thinking approach that enabled Central European intellectuals to envisage and ultimately construct a free Central Europe following the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. “The Moor has done his duty, the Moor can go.” After 1991, the idea of Central Europe materialized, gradually diminishing in significance.

Amid the turmoil of World War III, the concept of Central Europe became indispensable for Ukraine, turning into its existential interest and a clear vector for the future. What made this idea so alluring that it captured the minds and dreams of millions of Ukrainians, much like it had previously for Czechs, Hungarians, Slovaks, Poles, and other Central, Eastern, Southern, and Northern Europeans?

Fundamentally, the core of this idea lies in the concept of equality. The collective mindset of Central European peoples has been shaped by numerous traumas, national tragedies, and defeats spanning centuries. Over the past few centuries, this painful experience has been associated with larger and more powerful neighbors with imperial and colonizing ambitions. From time to time, these powers engaged in conflict with each other, turning the lands of Central Europe into battlefields. On other occasions, they brokered agreements, often to the detriment of and without the consent of Central European peoples.

This is how the concept of equality became ingrained at the heart of the Central European idea. The very course of history created the conditions for all the colonized peoples of Central Europe. After enduring numerous humiliations and navigating the arduous paths of national revival, they envisioned a reality where they would stand as equals among equals – where no external force dictates, mandates, or makes decisions on their behalf.

The driving force behind the Central European idea has long been fear—the existential threat of being erased from the world map through absorption by neighboring imperial powers. This fear, soothed by the welfare of the common European project and lulled by the NATO defense umbrella, reignited again after the beginning of Russia's hybrid and later full-scale aggression against independent Ukraine.

The genocidal nature of this war has brought to the forefront the worst fears of Europeans who once naively believed that after the bloody lessons of World War II, mass atrocities and extermination were forever in the past. The absence of a fair tribunal for the crimes of communist regimes has resurrected unpunished evils, which, in 2022, shed all pretenses and took on the most bizarre forms.

The engine of fear underscores the primary necessity of the Central European idea: solidarity. The realization that it is futile to confront stronger and more numerous enemies alone compels Central Europeans to unite, seek a cooperation framework, and strengthen solidarity. When they do not, Central Europeans often face defeat and collapse. However, during safer periods of history, when fear diminishes and apathy sets in, the Central European idea quickly deteriorates. It becomes marginalized, transforming from a clear plan of action for the future into a mere metaphor from the art world. In this state, it becomes a subject of mockery for intellectuals perceived as disconnected from reality.

So, we have defined the Central European idea as a forward-looking aspiration for equality among peoples, achievable only through collective solidarity and often realized during times of threats (which persist continuously, though people may sometimes forget about it).

The main question remains: where is this ephemeral and ideal Central Europe located? Which countries and peoples are its constituents, and who is not allowed to join the club?

In my view, the answer to this question does not lie in geography. The term “Center” has often prompted us to reach for a compass and ruler, to scrutinize maps, yet its essence resides at the very core of the idea. The essence of the European idea revolves precisely around equality and solidarity, endeavors to balance powers across the continent to foster a safer existence for all. A stable security framework lays the groundwork for sustainable development, prosperity, and, consequently, the fortification of democracy, respect for minorities and the vulnerable, and equal opportunities for all.

We have expended considerable effort in pinpointing the Center when our quest should have been for Europe itself. Central Europe is the geographical locus where European ideals and values are being fought for. This was exemplified by Kyiv’s symbolic ascension to the capital of Europe in December 2013 – marking the first occasion in history when the European Union’s flags were raised on barricades. No permission was required, for the idea belongs to no one; it is expected everyone can adopt it – primarily on an intellectual, but at times, even in a primal, military context.

The ideals of equality and solidarity in confronting existential threats are not confined to Central Europe; they are quintessentially European, originating in Western Europe and later migrating to Central European regions, defined conceptually to distinguish themselves from Eastern Europe. Now, these ideals are advancing further eastward, even onto the battlefields of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. (The migration of these ideas is a captivating process; one might argue there's a constant exchange within Europe, but in reality, these ideas are dynamic. When they wane in France and Germany, they flourish in the Czech Republic and Hungary; when they gain prominence in Ukraine, they may recede in Poland or Slovakia).

But enough with metaphors. To me, Central Europe embodies a battleground where individuals strive to uphold values central to the purest European ideal — the very essence of Europe itself. We speak of principles such as equality, solidarity, fundamental human rights, and the establishment of a system of checks and balances for all, irrespective of size or strength. On a continent marked by a dense tapestry of diverse interests and forces, an idea emerged on how to coexist without infringing upon others' rights, thereby safeguarding one's own existence. This is the core idea of Europe, the Central European idea.

No matter how audacious it may appear, even amidst profound conflict, this idea persists in its eastward trajectory. It spreads like a contagion to those individuals whom we might presently wish to forget or despise, whom we emotionally deny the right to a European identity. The idea evolves according to its own principles, beyond our control.

Nevertheless, the truth endures: it advances steadfastly, pushing forward, probing crevices and overcoming obstacles, pressing ever deeper eastward. At present, it encounters resistance, halted by Russian tanks and bombs, yet it will prevail, as it always has, surmounting every obstacle in its path.

I earnestly anticipate the day when Ukrainians witness the Central European idea bubbling and struggling for survival beyond our country's borders. I hope for us to be spectators rather than protagonists in this struggle — to empathize, support, and marvel, while keeping the unfolding tragedy on stage separate from our own lives.

Much like I did in Kharkiv on Oct. 1, 2021, during the premiere of an opera depicting the tragic life of Vasyl Vyshyvanyi. Little did I know then that within five months, the empire would seek to extinguish millions of Ukrainian lives, akin to the assassination of the Austrian archduke. We were unaware that coordinates for future missile strikes were being entered into launchpads. Unbeknownst to us, on February 24, 2022, a great war erupted — one that could potentially escalate into World War III if Europe fails to recognize that this battle is not merely for the east or the center, but for Europe itself.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in the op-ed section are those of the authors and do not purport to reflect the views of the Kyiv Independent.