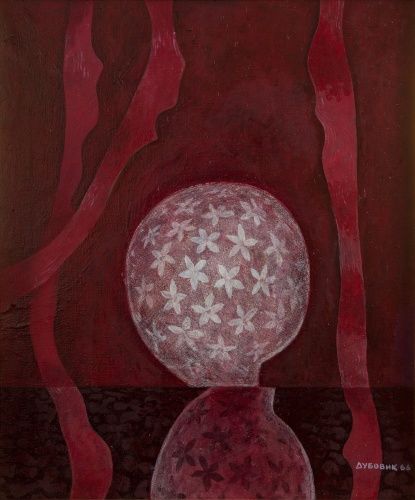

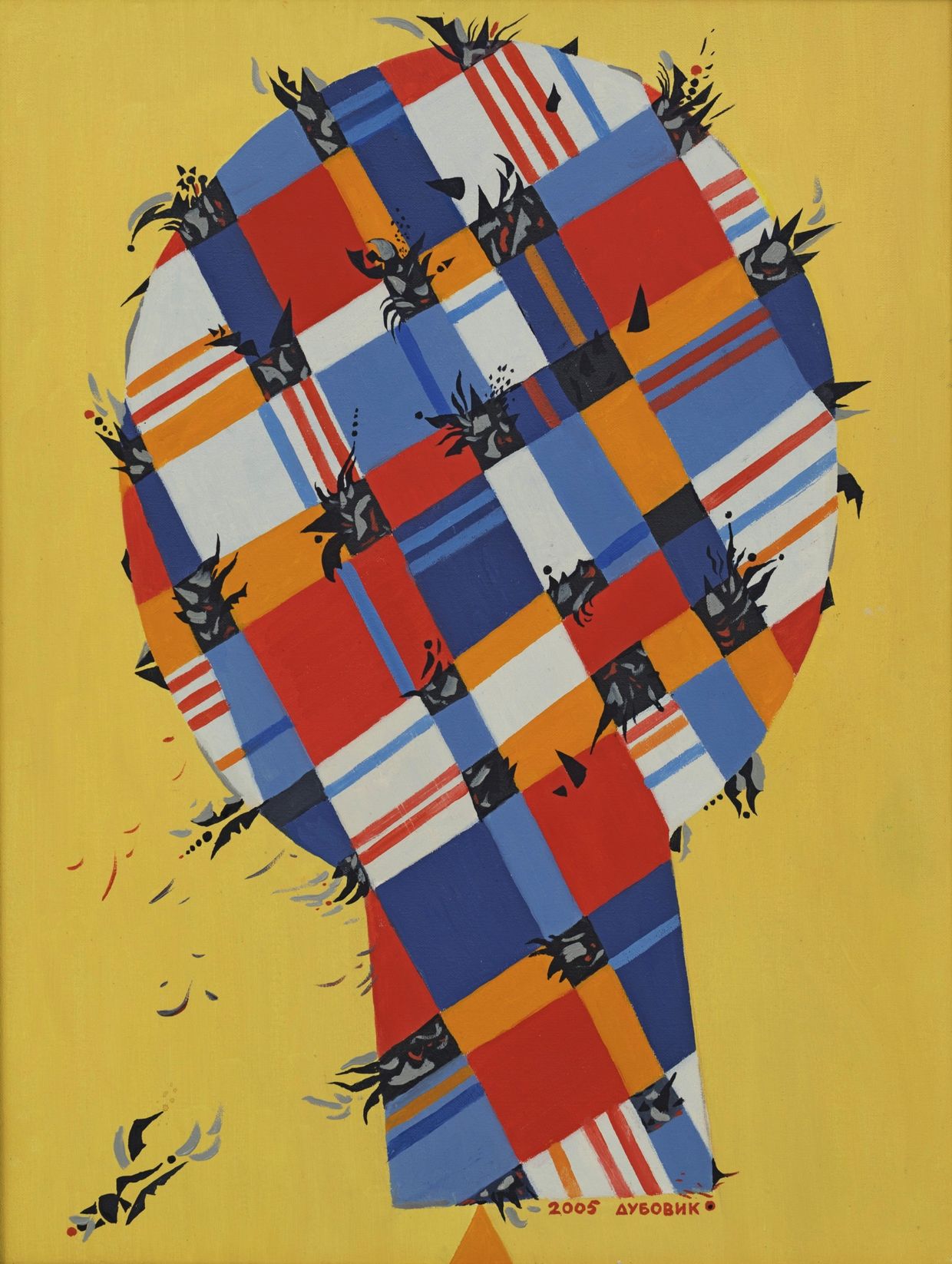

Painter Oleksandr Dubovyk, a legend of the “Ukrainian Sixties” movement who pioneered abstract expressionism during the Soviet Union, began experimenting with the concept of “bouquet” as early as 1966. While the philosophy has evolved over the decades, drawing inspiration from German philosophers and scientists like Heidegger, Leibniz, and Heisenberg, it is now understood by some Ukrainians as a symbol of a global cultural renaissance – led by Ukraine following its victory over Russia.

“White Bouquet” is described by Dubovyk in a manifesto published by the Stedley Art Foundation as a symbol of today’s civilization in its transition to a new paradigm. “It is a symbol of peace. It is a symbol of the Great ‘Ukrainian Idea,’” he wrote.

Dubovyk’s “Bouquet” embodies the seeds of humanity’s most divine beauty. Only through immense suffering – from the Holodomor tragedy, which gave rise to the term “genocide,” to today’s war crimes committed by the Russian army – can such art of profound meaning, vulnerability, and honesty emerge.

This Ukrainian pain and the beauty that arises from it are triumphant, carrying a distinct culture since the foundation of Kyivan Rus in the 11th century. As with Dubovyk’s paintings during the Soviet era, the most beautiful works often have to be hidden to survive.

The “Great Ukrainian Idea” is rooted in both Orthodox Christianity and Paganism, reflecting a deep connection to nature seen in Ukraine’s rich agriculture and high-quality food. Many Ukrainians today embrace these elements to connect with their earlier ethnic identities. Despite Russia’s continuous efforts to undermine Ukraine, this “Great Ukrainian Idea” has endured, with many Ukrainians feeling a stronger connection to their ancestral heritage than most Europeans, even if they cannot trace their family history back several generations.

Unlike European cities like Rome and Paris, which have become sanitized relics of former greatness, Kyiv today holds the promise of a brighter future, even in the face of Russian missiles.

“My advice to every young person in this room is to stay,” said the artist during his 93rd birthday at Ukrainian House, a cultural museum space in Kyiv, earlier this month. “You won’t regret it.”

Dubovyk’s contributions to abstract expressionism have been studied by many historians since the collapse of the Soviet Union. However, his writings and paintings on “Bouquet” have gained new significance following Russia’s full-scale invasion, serving as a philosophical foundation for a new Ukrainian identity.

Adherents of “Bouquet,” as a nascent but influential movement, are shaping the direction of Ukraine’s culture and history, with aspirations for a global cultural renaissance aligned with the Age of Aquarius, which Dubovyk references.

Evgeni Utkin, a prominent Ukrainian tech entrepreneur who runs a military manufacturing facility shelled by Russia in the early stages of the war, joins Kyiv-based art curators, donors, and museum directors in wearing “Bouquet” pins in Ukraine and abroad. His interpretation of Dubovyk guides his mission to produce war equipment on a large scale for his country. The two have spent many hours discussing philosophy and Ukrainian identity, and Utkin even introduced a new series from Dubovyk during the “Bouquet Kyiv Stage” festival, which the artist created during the pandemic.

All political movements require a philosophical foundation. The American Revolution drew heavily from the European Enlightenment (particularly Locke and Voltaire) while reviving a democratic tradition practiced in Ancient Greece. The Soviet Union relied on Marx, Engels, and Hegel, and their interpretations of class structures and labor theory. Despite their differences, both movements took up arms to overthrow a larger regime: weapons are vehicles of theory.

Today in Kyiv, a new social and political movement is forming around the “Great Ukrainian Idea.” The Youth of Ukraine, who came of age during the Revolution of Dignity, and their predecessors from the Soviet era are engaging in a dialogue, reevaluating the nature of history. How can Ukraine fully separate from Russia while acknowledging their intertwined histories? How can spiritual practices from Kyivan Rus be integrated with contemporary secular theory? The answer to these complex questions lies in art and the symbolism of “Bouquet.”

As the United States and Europe face an intellectual standstill, grappling with postmodernism and growing nihilism among Gen-Z and millennials (“we live in a world where there is more and more information and less and less meaning,” lamented Baudrillard in “Simulacra and Simulation”), Ukrainians are planting the seeds for a global renaissance.

Ukraine’s pagan influence offers a positive and inclusive ecological roadmap, unlike many contemporary environmental movements that alienate individuals by desecrating art. Its nationalism contrasts sharply with the far-right movements in the U.S. and Europe. The “Great Ukrainian Idea” is emerging on the international stage, showing that meaning still has a place in the world: If nothing truly mattered, people would not applaud to drown out the sounds of air sirens.

We are all Bouquet, and we are all Ukraine.

Editor's Note: The opinions expressed in the op-ed section are those of the authors and do not purport to reflect the views of the Kyiv Independent.