Although local elections often don’t make international news headlines or involve widely recognizable household names, anyone who cares about the state of liberal democracy would do well to pay attention to them. In Turkey, for example, recent elections not only revealed widespread dissatisfaction with the country’s autocratic president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan; they also offered broader lessons for long-struggling opposition parties about how to select effective candidates and run effective campaigns.

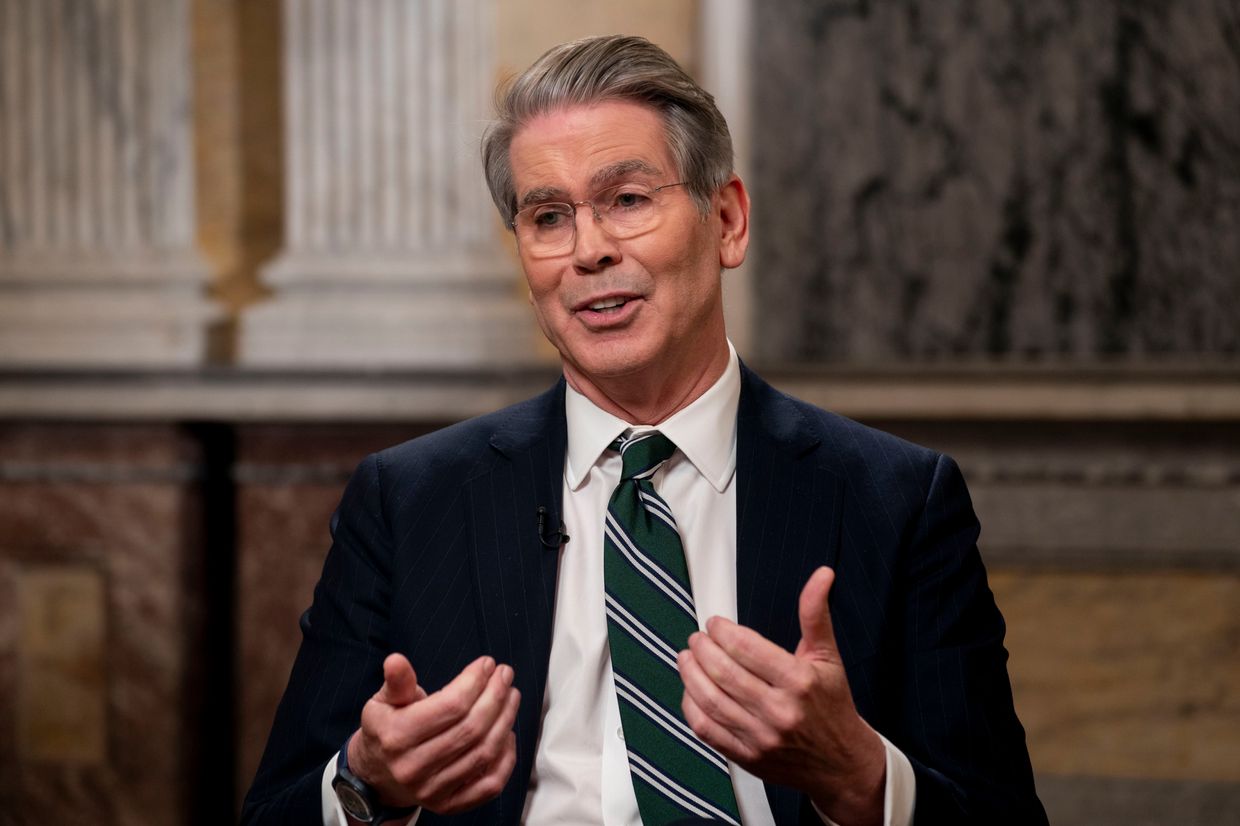

Poland’s local elections on April 7 were another case in point, because they offered the first signals of democratic parties’ relative strengths since the general election last year, when a liberal coalition finally ousted the illiberal Law and Justice (PiS) government. For Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s coalition, the elections were thus a kind of referendum on the government’s first four months in office.

But the outcome also has enormous practical significance. Major parts of national policies are implemented in accordance with decisions made at the sub-national level, which is also where European funds are distributed. And, of course, there are hundreds of positions to be filled by local politicians.

In the event, PiS received 34.3% of total votes, compared to 30.6% for Civic Platform (Tusk’s party), 14.25% for Third Way, 7.25% for Confederation, and 6.3% for The Left. But parties from the ruling coalition won almost all of the country’s 100 largest cities, as liberals typically do in municipal elections. Moreover, compared to the parliamentary election last year (36% and 31%), PiS lost support relative to Civic Platform.

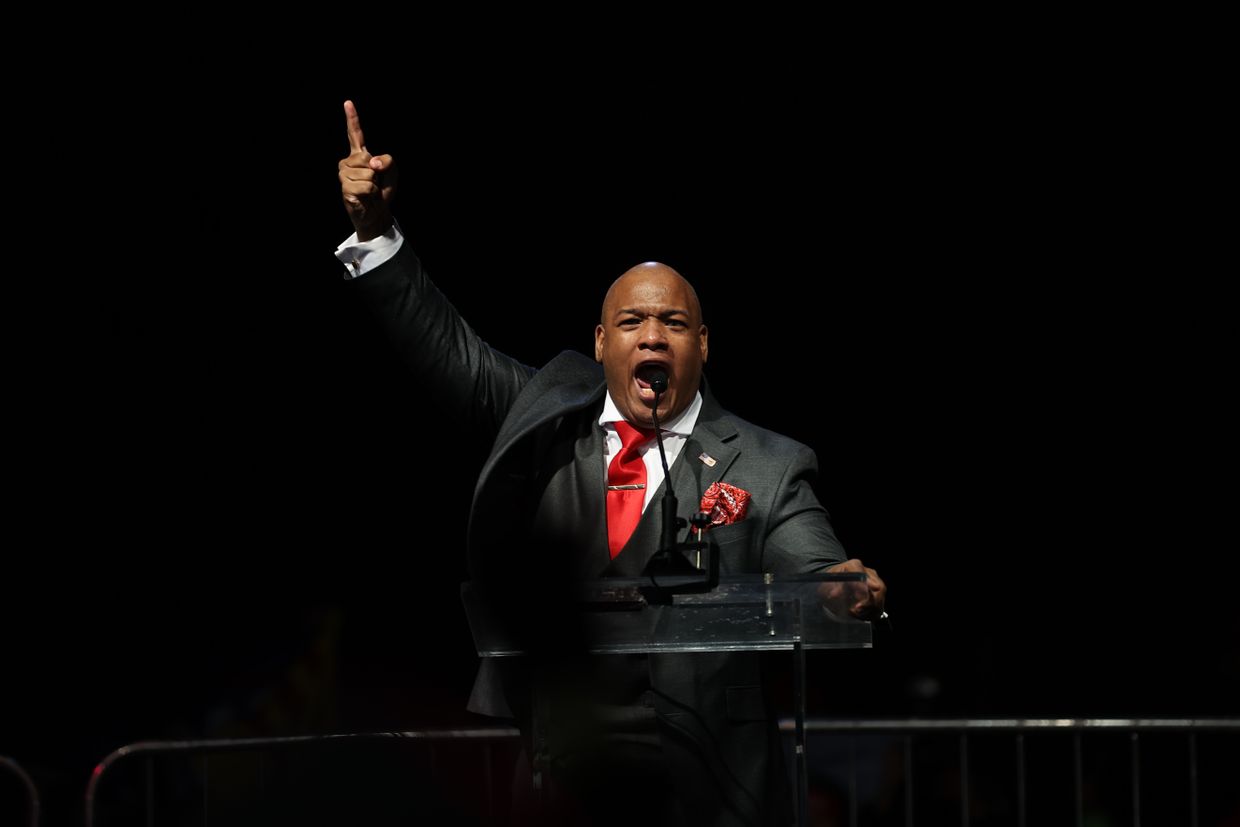

Since PiS won the greatest share overall, the results allow for competing interpretations, with only some declaring victory for Tusk and his partners (Third Way and The Left). But even if PiS can claim a victory of sorts, it appears to have been a Pyrrhic one. After winning nine of Poland’s 16 provincial governments in 2018, the party has now lost two.

While Third Way is hailing its result as a success, its share of the popular vote was 9.5 percentage points lower than the 2018 results for PSL, which joined with Poland 2050 to create Third Way in 2023. Despite strong pre-election polls, the nationalist and anti-Ukrainian Confederation had a weak 7% result.

That means the race for the Polish presidency in 2025 is Civic Platform’s to lose. Its candidate in the Warsaw mayoral election, Rafał Trzaskowski, won a resounding 57%, while PiS’s candidate, Tobiasz Bochenski, barely exceeded 20%. Another possible challenger, Third Way’s Szymon Hołownia, the marshal of the Sejm (parliament), has squandered much of his popularity with his cocksure behavior. His recent decision to postpone the Sejm’s consideration of bills to protect the right to abortion until after the elections was met with vociferous public criticism.

These results bode well not just for Civic Platform, but also for Polish democracy. Not until PiS is chased out of the presidential palace will Poland be able to move forward decisively in restoring the rule of law after years of populist misrule.

The elections in Kraków also brought good news for Civic Platform. Until now, Poland’s highly influential second-largest city has been ruled by an independent politician, Jacek Majchrowski. But he is retiring, and now Aleksander Miszalski (37.2%) of Civic Platform will face Łukasz Gibała (26.8%), another independent, in a runoff.

In Poznań, another influential major city, Civic Platform’s mayoral candidate, Jacek Jaśkowiak, performed somewhat worse than expected, and thus failed to win in the first round (43.7%). But anyone who has seen the PiS candidate in action knows that Jaśkowiak is really competing against himself. He has presided over a highly disruptive citywide reconstruction that would have guaranteed defeat for almost any other politician. In fact, Jaśkowiak has always been less a politician than a technocratic manager, which is ideal for Poland’s financial capital.

All told, PiS’s apparently stable level of support may be an illusion. At best, it can be thankful that its support has not declined by more. The only party with justified grounds for optimism is Civic Platform. That is good news for Poland, but it is also good news for Ukraine – and for Europe more broadly.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in the op-ed section are those of the authors and do not purport to reflect the views of the Kyiv Independent.