While waiting for a green light from Western countries to use their long-range weapons to strike targets deep inside Russia, Ukraine is relying on domestically produced drones, which are considerably cheaper than missiles and no less effective.

In recent months, Ukraine has increased the number of strikes using homemade drones against Russian critical infrastructure essential to powering Russia's war machine. Faced with attacks using dozens of drones at once, the Russian air defense proved to be overstretched and not always effective.

"Despite Russia's extensive air defense capabilities, there are limitations to protecting all targets effectively," Mattias Eken, a defense and security expert at RAND Europe, told the Kyiv Independent.

"The objective is to demonstrate to the Russian populace that the state's defense capabilities are insufficient, highlighting vulnerabilities within Russia," Eken added.

New challenges for Russian air defense

Since early September, Ukraine has conducted two mass attacks on Russia, reportedly using at least 144 drones in one and 158 in the other, according to the Russian authorities.

Moscow Oblast Governor Andrey Vorobyov said a residential building in the town of Ramenskoye was damaged as a result of the latest attack. According to Vorobyov, a 46-year-old woman was killed, and three other civilians were injured. The town is located 46 kilometers southeast of Moscow.

Kyiv has neither commented nor confirmed its involvement in these strikes.

The Sept. 10 attack targeted various Russian regions, including Bryansk, Moscow, Tula, Kaluga, Belgorod, Kursk, Oryol, Voronezh oblasts, and the Krasnodar Krai. Russia's Defense Ministry claimed that the highest number of drones—72—was reportedly downed over Bryansk Oblast, followed by Moscow Oblast (20) and Kursk Oblast (14).

"If Ukraine maintains pressure on Russian industrial and military sites and potential targets, that is going to have a significant consequence on how Russia fights," said Samuel Bendett, a senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security think tank, adding that Ukraine resorts to combined long-range attacks using various types of drones.

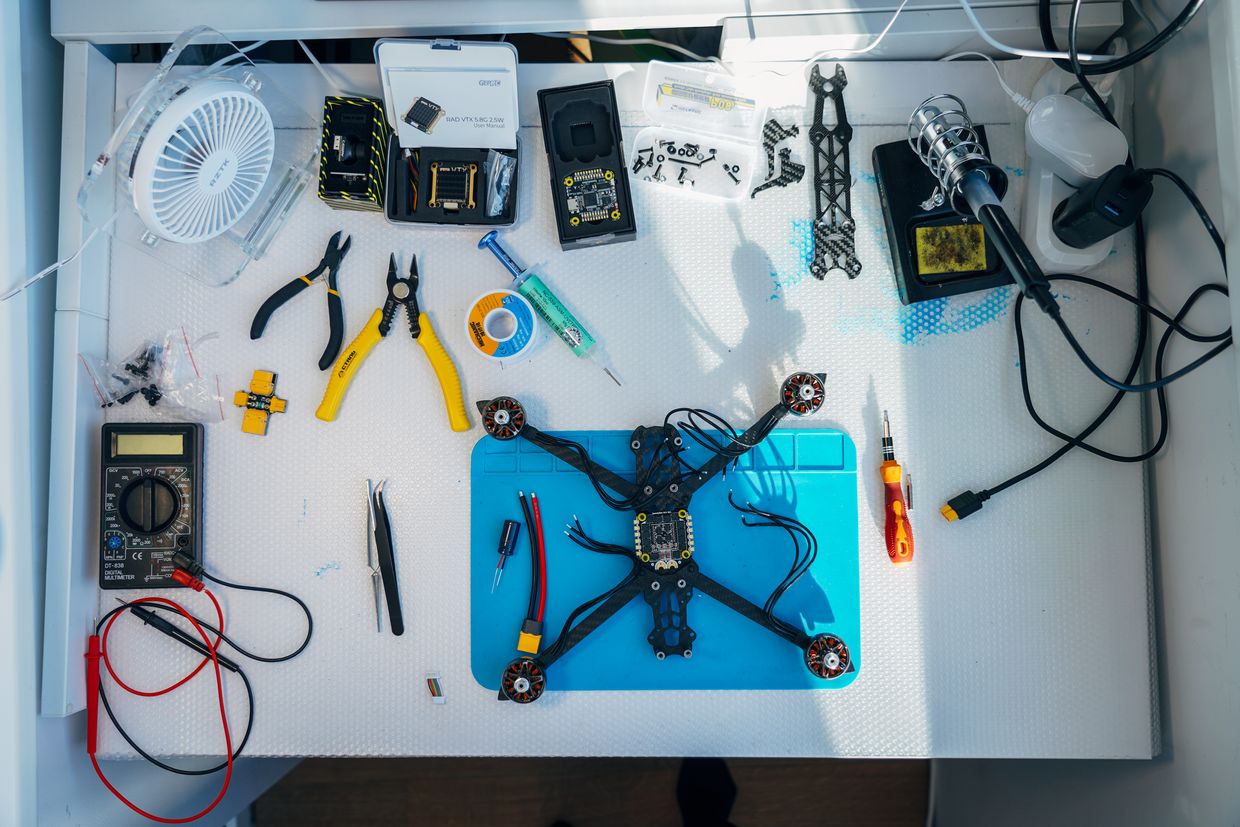

With the beginning of the full-scale invasion, drones became a game changer for Ukraine. The Ukrainian government began investing more in domestic production, creating incentives and grants, and simplifying bureaucratic procedures for manufacturers.

In the meantime, nearly 20 countries have united in a drone coalition, aiming to bolster Ukraine's arsenal of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs). In March, Digital Transformation Minister Mykhailo Fedorov said that Ukraine has expanded its drone market to the point where it can produce "more than one or even two million drones a year" with the help of partners.

As Ukraine increases its drone production, Russian air defense is increasingly showing its vulnerability. Recent Ukrainian targets have included oil refineries, airfields, weapons and ammunition depots. With dozens of drones entering vast Russian territory overnight, Russian air defense cannot cover it all.

"Utilizing a large number of drones plays a crucial role in overpowering and fatiguing Russia's air defense systems. Equally important is ensuring that the cost of drones remains lower than the missiles deployed to intercept them," Eken said.

"Ukraine's strategic use of long-range drone strikes is posing challenges for Moscow by creating dilemmas in defense planning." However, Ukraine's launch of a large number of drones is not the only issue creating challenges for Russian air defense.

"Ukraine's strategic use of long-range drone strikes is posing challenges for Moscow by creating dilemmas in defense planning."

According to Eken, Russian tactical radars are optimized for detecting jets rather than small, slow-moving targets like drones. Russian anti-aircraft systems such as Pantsir S1, Tunguska, and Strela often struggle to detect small drones until they are in close proximity, around 3-4 kilometers (1.5-3 miles), near the minimum effective range for engaging them with missiles.

"While systems like Pantsir and Tunguska are equipped with rapid-fire cannons as a backup, their effectiveness against small drones has been questioned," Eken added.

Is Russia ready to face even greater threats?

To counter Ukrainian drones, Russian forces are trying to reorganize their air defense units. "Russians are borrowing a page from the Ukrainian playbook right now," Bendett said, describing the recent approaches the Russian army took.

Russia has begun to launch mobile air defense units, as Ukraine does. The Russian Defense Ministry also plans to use mobile large-caliber machine guns and light air defense guns mounted on trucks and jeeps, Bendett said, calling this a "long-term solution."

"A lot of Russian commentators are very upset at their government's inability to deal with this threat," Bendett said.

"And they are calling for volunteer units like the ones that exist in Ukraine, where regular citizens patrol the skies listening to acoustic and visual signals to try and track these drones."

Yet this approach requires cooperation between the military and civil society, as in Ukraine. But this is not the case in Russia today, and it will take time to develop, the expert added.

According to Eken, Russia will likely also need to upgrade its radar technology to effectively counter the increasing presence of small, cost-effective drones. This technology integrates optical and acoustic detection systems to reliably detect drones at long ranges.

"Additionally, radio-frequency jamming will likely be a valuable tool in addressing this issue. Looking ahead, the development of novel anti-drone ammunition equipped with proximity fuses, as well as advancements in microwaves and lasers, may offer solutions in the medium to long term," Eken said, adding that the process of developing and implementing these technologies is expected to take "several years," while Russian defense industry is already "under strain" due to the ongoing war.

As Russia is trying to improve its air defense capabilities, Ukraine has announced the first successful test of a ballistic missile of its own production and presented a new development—the Palianytsia drone missile.

Experts do not believe that the new turbojet engine-powered drone will make significant changes on the battlefield, but they highlighted its ability, similar to a drone, to adjust its target and trajectory during flight.

As for potential ballistic missile attacks from Ukraine, they may be even easier for Russia to deal with, at least in theory, Eken said.

Russian air defense systems were primarily designed to intercept high-speed bombers, cruise missiles, and ballistic missiles. This is particularly evident in cities such as Moscow, where one of the world's few permanent stationary missile defense systems, the A-135, is deployed.

"Nevertheless, intercepting advanced ballistic missiles is notoriously difficult in practice, given their speed and trajectory," Eken added.