Editor's Note: This is episode 2 of "Ukraine's True History," a video and story series by the Kyiv Independent. The series is funded by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting within the program “Ukraine Forward: Amplifying Analysis.” The program is financed by the MATRA Programme of the Embassy of the Netherlands in Ukraine. Subscribe to the series' newsletter here.

Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022 shocked many around the world.

But anyone who paid attention to Ukrainian history would have seen it coming.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has offered several excuses for the invasion. One was to kill all the supposed "Nazis" in Ukraine. Another was to eliminate Ukraine's supposed military threat to Russia.

But the true reason was to annex Ukraine as a territory that Putin believes has always rightfully belonged to Russia. In speeches that recalled imperial times, Putin claimed that Ukraine's independence was a mistake that he intended to correct.

This meant conquering Kyiv, toppling the elected government, and destroying the Ukrainian national identity.

Putin's twisted vision isn't new. Russia has been doing this for close to 400 years.

In the 17th century, Russia violated its treaty with the independent Ukrainian communities known as the Cossacks to seize control and partition their burgeoning country. A century later, Russia massacred thousands of Ukrainian civilians, betrayed the Cossacks, and eliminated the last traces of their independent rule.

During the 1900s, Russia actively suppressed the Ukrainian language and culture throughout the empire. In the early 20th century, Vladimir Lenin's Bolsheviks, Russia's dominant political faction following the October Revolution, led multiple bloody invasions of the nascent Ukrainian nation to bring it under Soviet control.

Over the past 30 years of Ukrainian independence, Russia has tried to rule Ukraine through proxy politicians. When that stopped working following the 2014 EuroMaidan Revolution, Russia invaded eastern Ukraine and annexed the Crimean Peninsula in 2014, and greatly scaled up its invasion in 2022.

Russia has never ceased its assault on Ukrainian independence. This is just the latest episode. And this time, Ukrainians are determined to put it to an end.

A soldier nicknamed Raven fighting in Mykolaiv Oblast in October, said, "we will not allow what our grandfathers allowed to come to pass when they let us be subjugated."

From Kyivan Rus to the Cossack Hetmanate

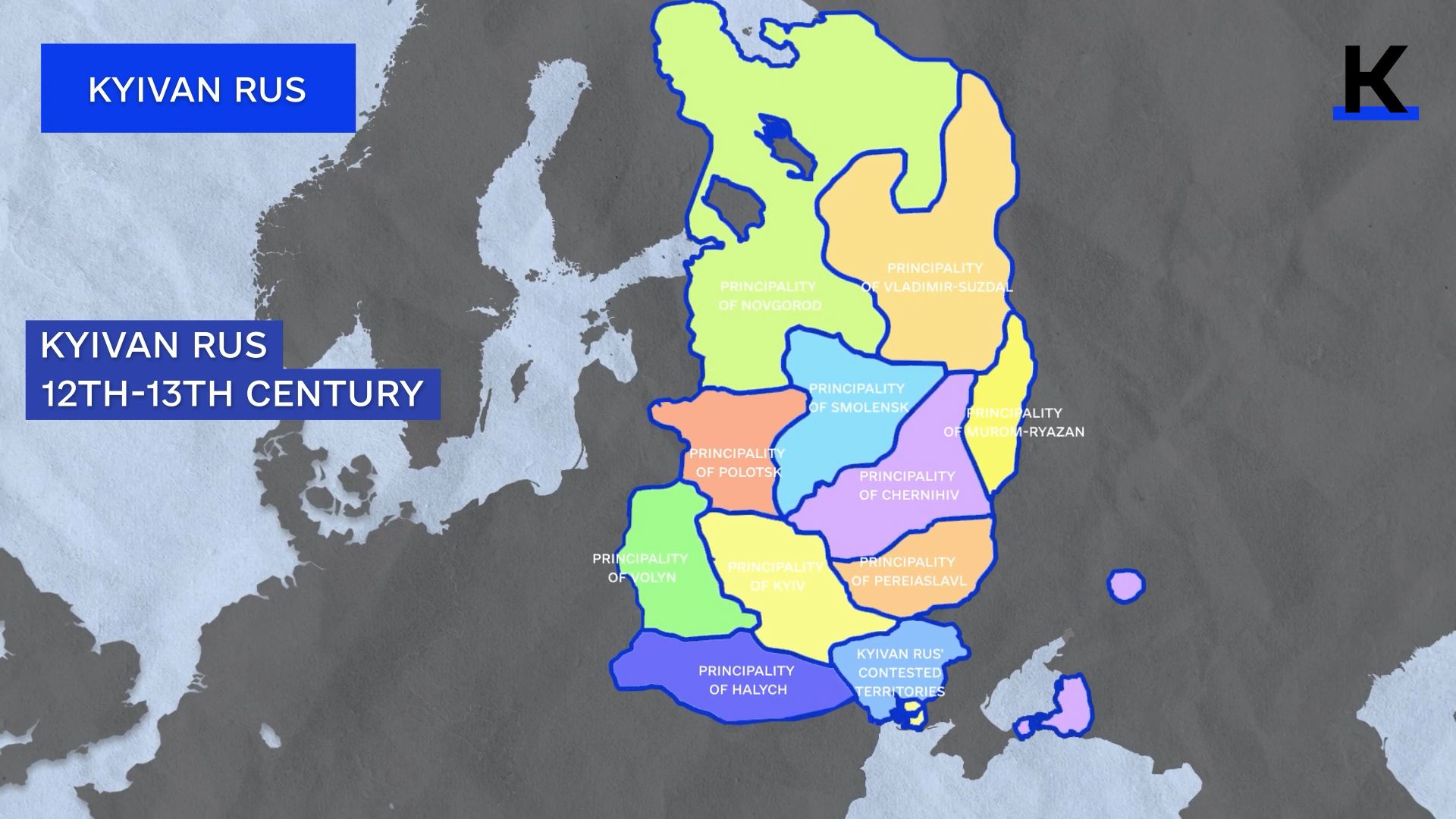

Ukraine's capital Kyiv was once the heart of Kyivan Rus, the most powerful medieval state in Eastern Europe. It was ruled by the Rurik dynasty, believed to be founded by Norsemen who traded and raided along the rivers of the region.

Internal strife would gradually tear the Kyivan Rus apart until a Mongol invasion in the middle of the 13th century finally destroyed it. It left behind successor states, such as Galicia-Volhynia, which Poland absorbed in 1349. Another successor state would become the Grand Duchy of Muscovy, the center of the future Russian Empire.

Over the centuries, the Ukrainian steppes began to be settled by Cossacks, groups of militarized people who drifted into the region over the centuries to freely live off the land and raid their neighbors. Many peasants drifted to the Ukrainian region, seeking a freer life.

The Cossacks were known for their militance, but also for their fierce commitment to independence, democracy and egalitarianism. This was a contrast from many surrounding empires with powerful nobility that kept their serfs in subjection.

By the 1600s, Cossacks in the region created a semi-autonomous proto-state called the Zaporizhian Sich, which was surrounded by several powers – the Tsardom of Russia, the Crimean Khanate, the Ottoman Empire, and the Polish- Lithuanian Commonwealth.

They all fought one another at different times in a series of shifting alliances.

The rise and fall of the Hetmanate

In the 1600s, the Zaporizhian Sich was under Polish rule, which the Cossacks resented.

Eventually, a strong Cossack leader arose – Bohdan Khmelnytsky.

Khmelnytsky led the Cossacks to victory against the Polish forces, establishing the Cossack Hetmanate, a Ukrainian Cossack state in the area of what is today central Ukraine.

To protect his newly created state against Poland, Khmelnytsky decided to court the protection of the Tsardom of Russia, with the two sharing the Eastern Orthodox fate. Under the treaty of Pereislav of 1654, the Hetmanate pledged allegiance to the throne of Moscow in exchange for military protection.

But it quickly became clear that the two sides understood the agreement very differently.

Khmelnytsky believed that his Hetmanate was going to be an independent power under Moscow's protection. Moscow saw it as a territorial acquisition.

Moscow began sending military governors to Ukraine, tried to collect taxes, and undermined the independence of the Ukrainian church. Moscow would send a noble to oversee local elections in Kyiv and told Ukraine that Tsarist warlords would take over the functions of government. Moscow also bribed military officers to rise up against the Hetmanate.

Moscow even made a truce with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, under which Ukraine would become a commonwealth protectorate.

Soon, the Ukrainian Cossacks clashed with Russian forces. The Cossacks prevailed at the Battle of Konotop in 1659. However, again, their leaders were unable to capitalize on their military victory.

Outmaneuvered politically by Moscow, Khmelnytsky's son signed the Articles of Pereislav, which limited the Cossacks' independence.

Less than a decade later, Moscow and Poland would divide control of the proto-Ukrainian state amongst themselves along the Dnipro River.

The end of the Cossack Powers

After decades of instability, known as the Ruin, the Hetmanate found another strong leader: Ivan Mazepa. Under his rule, which lasted from 1687–1708, Ukrainian culture flourished. Kyiv's golden domes bear witness to his legacy.

Then came the Great Northern War between Russia and Sweden. Mazepa fought for the Tsar, but after disputes with Peter I of Russia, Mazepa and some of his Cossacks switched sides.

Russia's Peter I ordered revenge. In November 1708, his forces smashed into hetman's fortified capital of Baturyn, located in modern-day Chernihiv Oblast. Once inside, the imperial troops executed up to 15,000 people, including civilians, among them women and children.

Many were quartered, broken on the wheel, or impaled on stakes.

Sweden's King Charles XII and Mazepa were crushed at the Battle of Poltava. This was the beginning of the end for the Hetmanate.

The true death of the Cossacks came after the coup of Catherine II. She asserted imperial autocracy, cracking down on the Cossacks' self-governance. In the region of Sloboda, which ran from modern-day Sumy to Kharkiv oblasts, Cossack regiments were reforged into Russian imperial army units.

In 1764, the Cossack system was abolished and replaced with Russian institutions.

The authority of the Cossack Hetmanate was liquidated, and the last Hetman of the Zaporizhian Host was ordered to renounce his authority to a Russian governor-general.

Subsequently, Moscow also eliminated the autonomous Cossack way of life.

The final blow landed in the 1770s after the Cossacks helped Moscow defeat the Ottoman Empire. Russian troops surrounded the Sich, surprising the Cossacks.

Faced with overwhelming firepower and a threat to their families, they were forced to surrender. This was the end of the Cossack Hetmanate.

Suppression of national identity

The notion of a Ukrainian national identity emerged in a big way in the 19th century, inspired by other national movements in Europe.

Moscow began suppressing the Ukrainian language and identity, afraid of separatism. Top writers and intellectuals were imprisoned or exiled. That included Ukraine's most famous author and artist, Taras Shevchenko.

The Russian Empire banned the publication of scholarly, religious, and educational books in Ukrainian in 1863. Tsar Alexander II then banned the printing and import of Ukrainian language publications altogether in 1876 with the Ems Decree.

The exodus of Ukrainian cultural figures to more liberal Austria-Hungary, where no ban on the Ukrainian language and culture existed, allowed Ukraine to preserve its national identity.

Meanwhile, Russia actively tried to undermine Ukraine, referring to it as "Malorossiya" or "Lesser Russia," which is how Putin views much of Ukrainian territory today.

Malorossiya, which means little, lesser, or minor Rus, is a term that began appearing in the 13th century, referring to Galicia-Volhynia.

The term began to resurface in the 17th century to refer to geographical or ecclesiastical subdivisions within the area of what is now Ukraine.

After the Pereiaslav Treaty, Moscow began using it to refer to the Cossack Hetmanate to back its claim on the entire region. Putin's Russia, fond of historical revisionism, has been trying to bring back the term.

The 20th century

In the early 20th century, the Russian Empire was crumbling, facing military, economic, and political setbacks. In 1917, amid the ongoing World War I, Russia faced two revolutions. Ukrainians saw it as an opportunity for independence.

Between 1917 and 1921, the land that is now Ukraine was fought over and controlled by more than half a dozen armed factions.

Kyiv faced two successful waves of assault from Russia during this time. Eventually, Ukraine was swallowed by the Soviet Union.

Ukrainian People's Republic was created in 1917 which proclaimed its independence the following year. Ukrainian officials gathered a parliament (Central Rada), elected a leader (historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky), and sought international recognition.

After a failed Bolshevik uprising in Kyiv in early 1918, Russia began a military campaign against Ukraine.

The officer in charge of the invasion was Mikhail Muravyov, who tortured the inhabitants of each new city he conquered. The rest, he let his men loot.

Ukrainian forces, mostly students, were able to delay the swiftly advancing Russian troops in the Battle of Kruty, about 120 kilometers northeast of Kyiv.

Despite the Bolsheviks winning the battle and sacking Kyiv, Ukraine was able to sign the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Central Powers and soon, together with the German army, pushed the Bolsheviks out of Ukraine.

While in Kyiv, German forces didn't oppose a coup led by Pavlo Skoropadskyi, who was proclaimed the new hetman, meaning the military leader of the Ukrainian State.

Skoropadskyi's reign proved unsuccessful.

After Germany's defeat in World War I, he himself was deposed by the reemerged Ukrainian People's Republic led by Symon Petliura.

The following year, Soviet Russia swept in once more, finally bringing Ukraine, poisoned by internal fighting, under its control.

After taking power, the Soviet regime first promoted Ukrainian culture to appease the hostile population, yet later turned to terror in fear of popular uprising.

In the 1930s, Ukrainian writers Valerian Pidmohylny, movie director Les Kurbas, and painters Mykhailo Boychuk and Ivan Padalka were tortured, imprisoned, and executed.

They have been known as the Executed Renaissance, as most of them were shot by the Soviet regime during the Great Terror in Sandarmokh.

21st century

Moscow's designs on Kyiv continued into the 21st century.

After Ukraine became independent, Russia tried to maintain control through proxy politicians. These included pro-Russian lawmaker and oligarch Viktor Medvedchuk and former President Viktor Yanukovych.

This failed. In 2004, Yanukovych's fraudulent election victory was resisted by the Orange Revolution, a series of protests that annulled a rigged runoff vote in his favor.

Yanukovych would run again in the 2010 presidential election and prevail against his main opponent Yulia Tymoshenko. Yanukovych's Party of Regions, which had a collaboration agreement with Putin's party United Russia, would be a powerful force in Ukrainian politics for years.

In 2013, when Yanukovych defied the popular will and refused to sign an association with Europe, people rose up again in the EuroMaidan Revolution.

No matter what Russia wanted, Ukraine was pulling away toward Europe.

In the end, Putin was left with one option to cling to what he sees as Russia's imperial possession: a direct invasion that began with the occupation of Crimea and eastern parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in early 2014.

When the nine-year occupation of Crimea, Donetsk, and Luhansk failed to shake Ukraine's Westward course, Moscow gave up all pretense and launched a full-scale ground war to destroy and conquer Ukraine.