Editor's Note: Stanislav Aseyev is a Ukrainian writer, journalist, veteran, and a survivor of the Izolyatsia prison in Russia-occupied Donetsk, infamous for its torture of prisoners. He was the first Ukrainian journalist to see to the Sednaya prison and death camp in Syria after the fall of Bashar al-Assad's regime in 2024.

This piece was originally published in Ukrainian on Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. It has been translated and republished with the author's permission.

I conceived this piece as an attempt to compare the modern systems of dehumanization that still exist and function in different corners of the world.

After spending 2.5 years in Russia's secret prison Izolyatsiya and enduring its torture regime, I felt it was essential, both as a survivor and a writer, to examine the elements of a similar system on another continent. Are these systems shaped by ethnic factors, or is the extreme cruelty humans inflict on one another simply a manifestation of our species’ inherent inclination for sadism? Syria's Sednaya prison serves as yet another argument for the latter view, challenging the very notion of humanity’s ethical progress.

Through the valley, to the shadow of death

Beirut. It's 18 degrees Celsius. The hum of an Israeli drone overhead, chaotic traffic, bombed-out buildings, yellow Hezbollah advertisements, checkpoints, and men with bright balloons against a backdrop of ruins.

I ask my guide who they are. "Refugees," they say — Syrians and Palestinians trying to make a living, however meager, by selling balloons, fish, and birds — literally pushing them into car windows. Meanwhile, motorcyclists narrowly avoid collisions, cut off by dented cars: Finding a car without damage in Beirut is nearly impossible, and no one seems to care anymore.

This is where the road to Syria's Sednaya prison begins — another of humanity's grim discoveries in the realm of torture and executions.

One can now enter Bashar al-Assad's death camp only through Lebanon.

I arrived in the country accompanied by officers from Ukraine's Defense Intelligence (HUR). They are tasked with evacuating Ukrainian citizens from Syria and simultaneously ensuring my safe passage to Sednaya with the highest possible level of security.

The issue of safety begins in the Beqaa Valley, where we must travel to reach the Syrian border. Like Beirut, the valley is fragmented into various zones of influence but in a more chaotic and informal way. The term "control" here is relative — no one controls anything completely in Beqaa.

The valley is divided between Hezbollah and local gangs involved in arms, drug, and human trafficking. It encompasses both small, ordinary towns and isolated hideouts in the mountains, where various groups take refuge. Additionally, some Russians have partially moved into Beqaa after fleeing Homs, which was the worst piece of news for me amid all the other risks. I was warned about this back when we were in Istanbul, heading here.

Having received some guarantees of safety, we reach the Lebanese-Syrian border, where an unusual situation arises regarding our passports.

The issue is that Syria does not currently stamp passports for entry or exit due to the ongoing change of power. This creates a strange scenario: You leave Lebanon seemingly for nowhere and return as if from nowhere, judging by your passport stamps.

Before departing Beirut for the Syrian border, we had conflicting information about who controls the border, including the possibility that it might be entirely unguarded.

However, at the very first checkpoint, we encounter men in military uniforms — members of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, effectively the new Syrian regime. The second checkpoint is under the same group’s control, though the scene is slightly different: About a dozen armed civilians rush to the vehicle, shouting and gesturing for us to move quickly.

Upon entering Syria, the changes in the country become immediately apparent: Syrians have removed or painted over Bashar al-Assad’s portraits wherever possible, replaced the red stripe on the national flag with a green one, and added a star, and just outside Damascus, you come across burned-out tanks and even a destroyed Russian Pantsir air defense system.

'The human slaughterhouse'

In Damascus, we are met by Ali, a representative of the new regime, who has agreed to accompany us to Sednaya. The prison is about a 30-minute drive from the capital.

Even as we approach this concentration camp, its scale is staggering. It resembles a small, enclosed city, surrounded by barbed-wire fences, watchtowers, and, reportedly, a perimeter laden with landmines.

During our visit, the prison caught fire, shrouding its grounds and buildings in acrid smoke.

The first thing that catches your eye on the grounds of Sednaya is the haphazardly dug pits surrounding the camp. These are the results of searches for underground prison chambers, where the majority of the inmates were believed to have been held.

Though we arrived in Sednaya late in the day, even at that hour, we encountered a Syrian family walking through the prison grounds, desperately searching for any trace of their relatives who had been detained there.

Every building had already been searched, but such families still hope to find hidden underground chambers whose entrances may have been overlooked.

Relatives post photographs of their loved ones around the grounds — people who disappeared behind the prison’s walls many years ago.

Of everything I witnessed in Sednaya, this was, for me personally, the most haunting sight.

After the prison administration seemingly vanished into thin air, abandoning thousands of inmates in their cells, no one can definitively say how many people were held here — or might still be here.

It is evident that if underground floors exist, no one has provided food or, worse, water to any prisoners there for weeks. This makes the likelihood of finding anyone alive in such chambers slim. The entire site feels like a cemetery, but one that still stirs with faint signs of life.

On our way back, Ukrainian citizens evacuated from Syria by the Ukraine's Defense Intelligence recounted that in Latakia, nearly everyone has acquaintances or relatives who had been imprisoned during Assad's regime.

One former prisoner recalled counting 72 stairs when he was led, hooded, up from his cell to another level, and then back.

The use of underground detention practices was prevalent here, much like it is in Russia.

Are they still in the dungeons or already executed?

However, the search for underground chambers at Sednaya yielded no results, and by the time of our visit, it had been called off. According to our guide, Ali, the theory of underground facilities is based on information from two sources.

First, some of those released from Sednaya recount being held in windowless rooms for a time before being moved upstairs. Second, according to Syria’s Interior Ministry, the number of prisoners at Sednaya was estimated to be in the tens of thousands, while only about 2,000 have been freed. However, this argument is undermined by the torture and execution chambers at the prison, which had been set up for large-scale operations.

The discovery of a press used for crushing people, the so-called "acid room," and systematic executions that human rights organizations have documented all these years suggest that the Assad regime has simply killed the missing prisoners.

According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, based in London and monitoring the war in Syria, more than 30,000 prisoners were executed or died from starvation, medical neglect, or torture between 2011 and 2018.

The first floor of Sednaya housed administrative facilities such as the kitchen. There was also something resembling a "temporary detention isolation unit," where those recently brought to the camp were held in cages before being sent to the upper floors.

Above these areas was the prison’s administration's offices. The administrative staff of Sendaya has fled, all of them.

The upper floors of Sednaya were designated for prisoners: Divided into three blocks, they housed thousands of inmates in nearly bare cells. Ali mentions that in some cells, up to 50 people were crammed in, forcing the prisoners to sleep on their sides, pressed together to fit on the floor. It's important to note that this took place in a desert environment, with extreme temperature fluctuations: from scorching heat during the day to freezing cold at night.

I've heard of such sleeping arrangements from the criminals I met in the Izolyatsiya prison in Donetsk — a similar practice existed in various penal facilities in Ukraine and Russia in the early 1990s. In general, the survival tactics of prisoners often mirror the methods of control over them, so places like Sednaya, Izolyatsiya, or Abu Ghraib share many common elements.

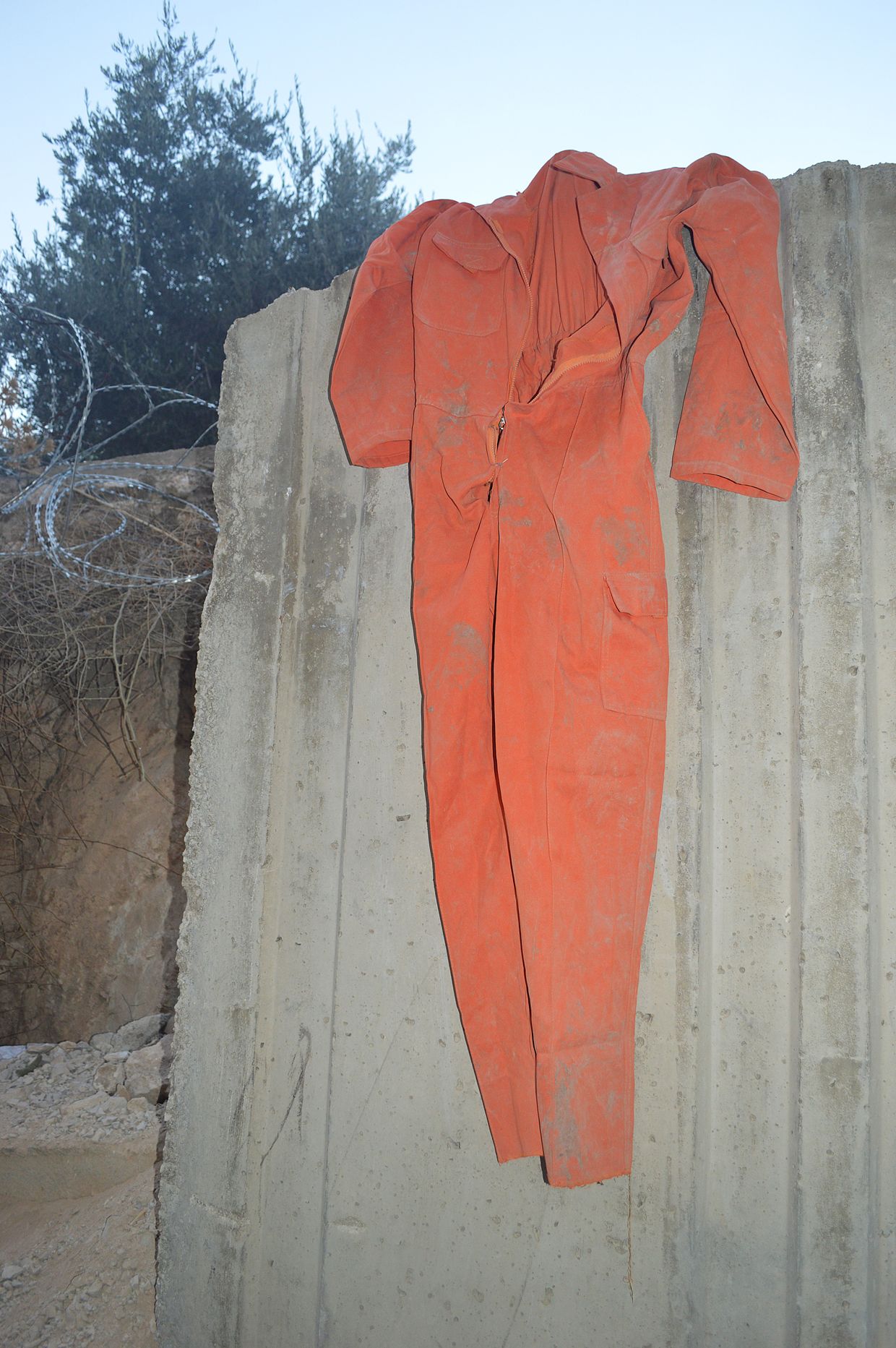

What reminds about the executions in Sednaya now are the clothes of the condemned prisoners: their bright orange jumpsuits are scattered across the floor, hang from the ropes, and are intentionally placed near the prison building, for journalists to see.

In the final years of its existence, Sednaya became primarily a death camp, where the torture and execution of prisoners were systematic, earning it the grim name of "human slaughterhouse" among locals. Prisoners had their spines broken by special boards, were beaten, raped, starved, and executed, with their remains dissolved in acid.

Another eerie parallel with Izolyatsiya emerges: During Assad's reign, Sednaya instilled such fear among Syrians that its name was often whispered in hushed tones to avoid attracting unwanted attention. This evokes comparisons to the infamous Izolyatsiya prison, where even public transport in Donetsk would avoid stopping near the facility due to the fear it inspired.

Today, Sednaya is a thing of the past.

Now, as with any other abandoned Syrian building, the sun shines through its empty cells, illuminating the walls for the cameras of countless journalists, for whom it is just another job.

One can hope that the suffering here has ended — but only time will tell whether the Syrian people will truly leave it in the past.