At the opening of an art exhibition in Kharkiv’s Yermoliv Center on Aug. 29, 18-year-old artist Veronika Kozhushko, also known as Nika, could be seen jumping on a small trampoline before she landed on her feet with a breathless smile.

The following day, Russia killed her.

Russia launched glide bombs at Kharkiv on Aug. 30, killing at least seven people and injuring over 90 others. The city has been a frequent target of Russian attacks since the beginning of the full-scale invasion in 2022 given its proximity to Russia.

Over 100 Ukrainian artists have been killed since 2022, according to the writer’s association PEN Ukraine. With the death of Kozhushko, Ukraine not only lost yet another artist but one that was just at the start of her life and career.

“Nika had been drawing since childhood, but with the onset of the full-scale invasion, she began to focus even more on it,” Arina Nikolenko, her girlfriend and fellow artist, told the Kyiv Independent.

“She felt a specific need to contribute to the creation of contemporary Ukrainian art, which she had come to love so much.”

‘She was the culture itself’

Kozhushko was a staple at various exhibitions, shows, and literary events in Kharkiv.

“No event at the Kharkiv Literature Museum went by without Nika,” recalled Maryna Hrachova, who works at the museum.

“She volunteered (at events), drew, filmed, and simply enjoyed being there (at the museum) — absorbing what was happening, adding color (with her presence), and transforming her impressions into art.”

The garden of the Kharkiv Literature Museum, which is surrounded by sketches of famous writers not only from the city but all around Ukraine, was often a favorite meeting place for her and her friends.

Kozhushko was “always creating art whenever she had a moment,” her close friend Rehina Avksentieva said. “She created modern Ukrainian culture and was for me a living example of art in human form.”

“Though she was so young, she was everywhere — reaching out for knowledge, for the study of Ukrainian culture. She was the culture itself. Emotional, very sincere, creative. Nika was the bud of a strong flower that was about to bloom in full strength,” her friend Liudmila Yankovska added.

Kozhushko and her peers are part of a generation that has come of age during Ukraine’s EuroMaidan Revolution, Russia’s illegal annexation of the Crimean Peninsula, Russia’s invasion of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in 2014, and the start of the full-scale war in 2022.

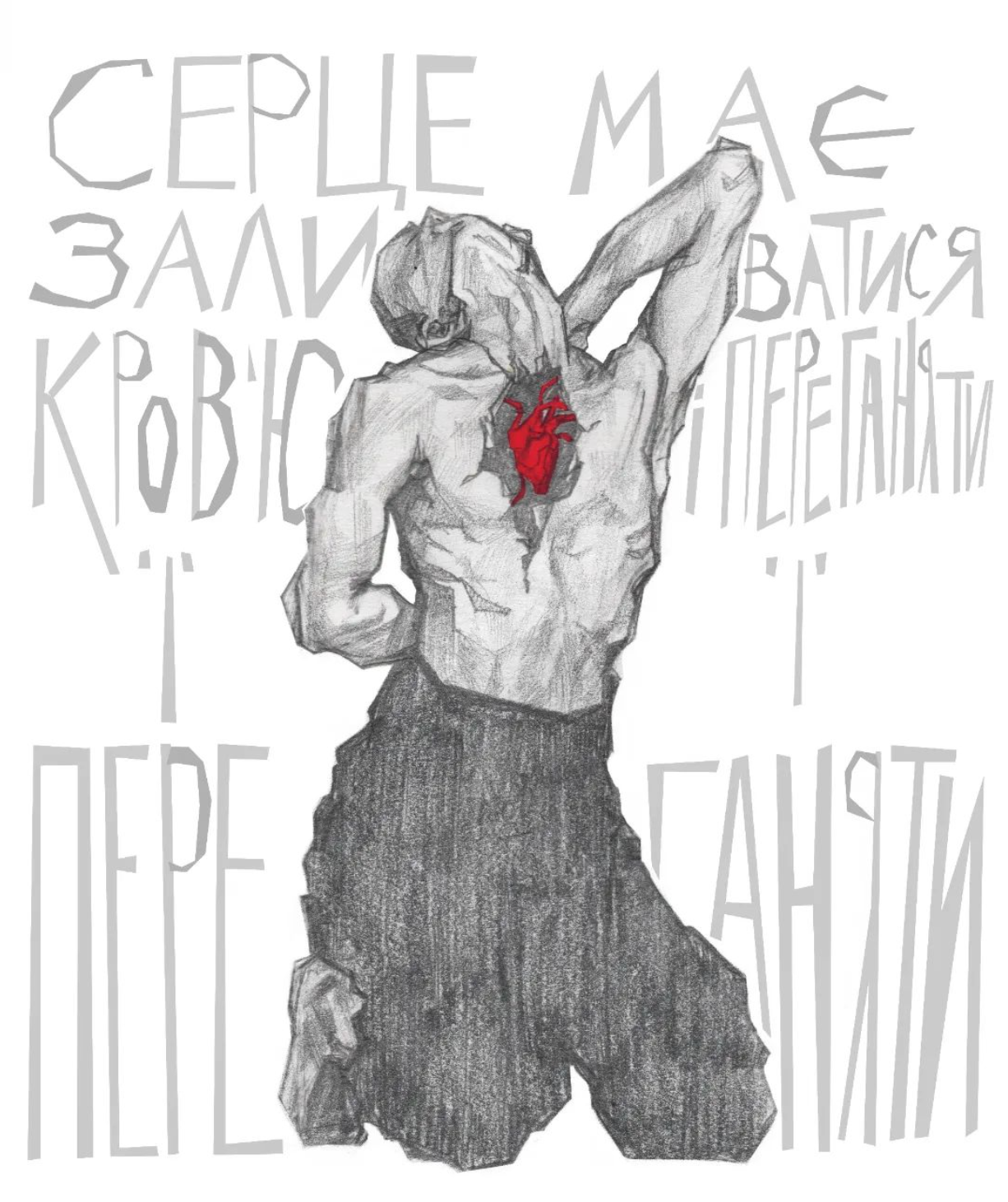

The importance of Ukraine’s fight to defend its sovereignty against Russian aggression strongly features in Kozhushko’s work.

Focusing on her art even more after the start of the full-scale war allowed her “to show people what concerned her,” according to Nikolenko. She had a talent for noticing and sketching what might have seemed to others like random or insignificant things and giving them a special meaning.

“I really admired how Nika felt the world around her and noticed details,” Yankovska said. “She deeply absorbed everything through herself and expressed it in her art.”

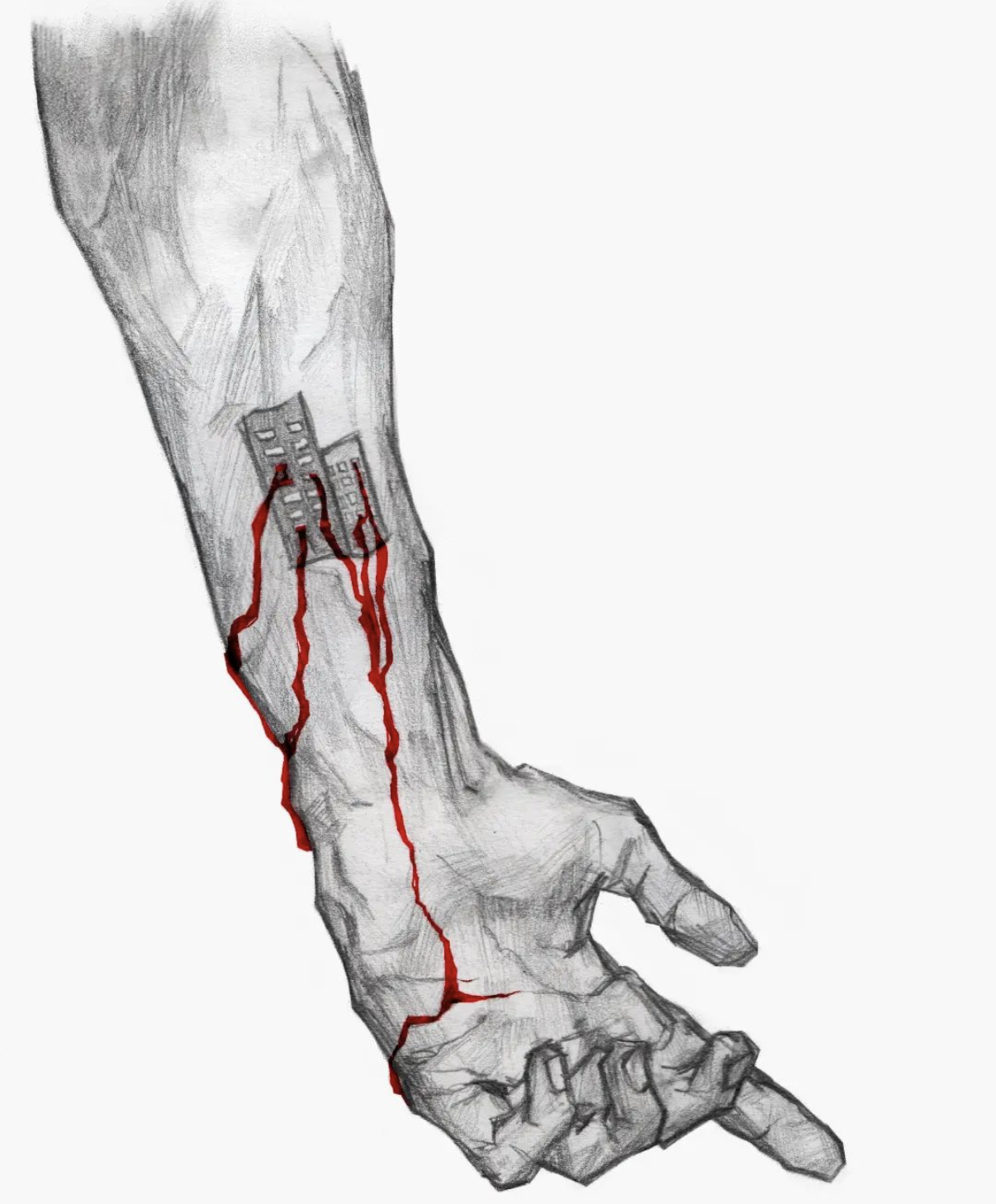

In one ink sketch posted on Kozhushko’s Instagram, an apartment building’s ruins are drawn in blue ink, while stick figures – rendered in white ink – are superimposed over the wreckage.

The contrast of the colors suggests they occupy different realities, as though their lives, captured in fleeting moments of everyday tasks like folding laundry or cooking, are already part of a memory.

Smoke swirls ominously above them, intensifying the sense of quiet despair and underscoring the fragility of existence during wartime, where life and death coexist, separated by only the thinnest veil.

Kozhushko was also passionate about writing poetry. In one poem that she was particularly proud of, shared with the Kyiv Independent by Nikolenko, Kozhusko wrote:

“The most bitter poems are about God.

They smell of despair, incense, and sorrow.

The Almighty is mentioned

Only in the context of absence.

Atheism awakens

Only in devout Catholics.

Take up the cross,

to the mangled paws,

Write how you will end up in hell.

And as long as you cross out signs,

You develop hemophilia.

God applies to wounds

Only the empty pages of the Bible.”

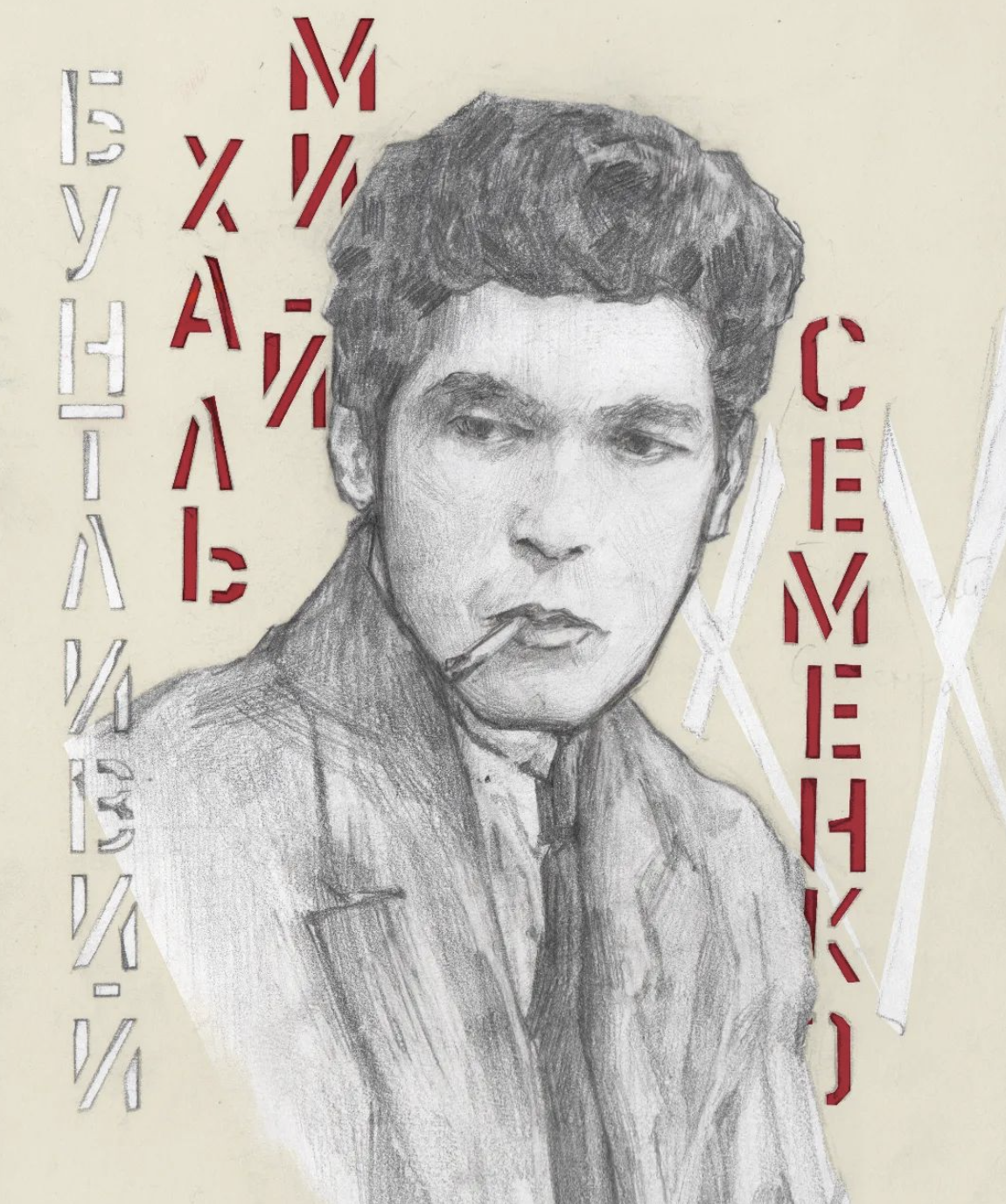

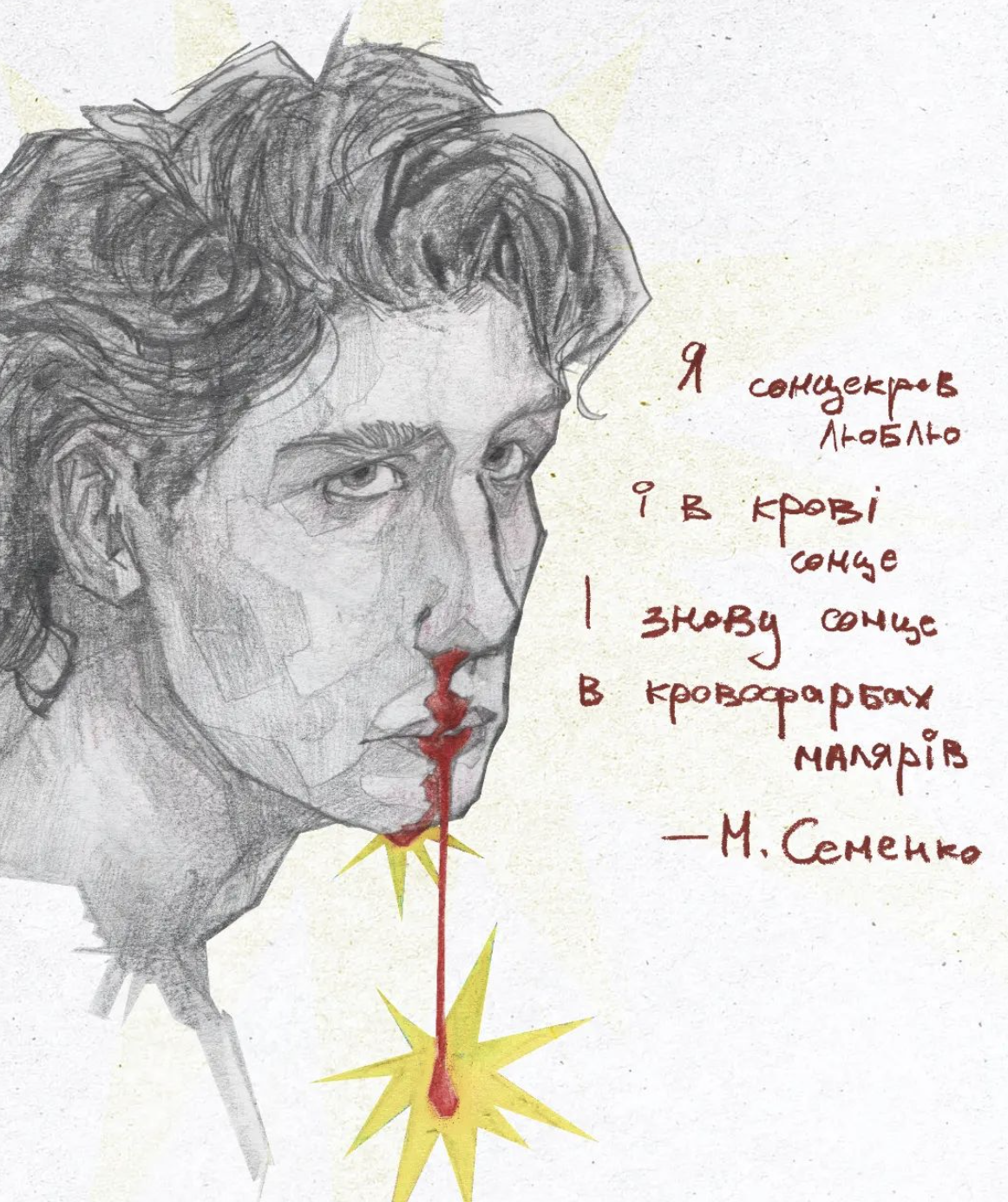

Kozhushko’s writing was partly inspired by the poets of the Executed Renaissance, a generation of Ukrainian artists from the 1920s and '30s, many of whom lived in the Slovo building in Kharkiv. They were imprisoned, tortured, and killed by Soviet secret police during Stalin's purges.

For those who knew and loved Kozhushko, it’s painful to realize that she has become part of “the new Executed Renaissance” of Ukrainian artists who have perished in Russia’s war.

Kharkiv’s cultural community “has a different level of understanding and feeling toward one another,” Anastasiia Semenenko, Kozhushko’s friend, said.

In such a tight-knit community, the death of Kozhushko now feels “like an atom has been destroyed in our molecule.”

‘Aware of her freedom in every breath’

Kozhushko was an example to live by not just for her peers but for Ukrainians of all generations, according to Hrachova.

“It might sound paradoxical, but I couldn’t teach her anything, even though I’m much older. She was the one teaching me, without even realizing it,” Hrachova said.

“I looked at her and thought of what I could have become, but didn’t, because I was a child of the Soviet era. She, born in a free country, and aware of it in every breath, was entirely different: it felt as though her national consciousness had been instilled in her before birth.”

Kozhushko was also “a true non-conformist” even during her school days, according to Hrachova.

The mayor of Kharkiv was once set to visit Kozhushko’s school, and the students and teachers were supposed to thank him for the renovations made to the school building.

The principal “begged Kuzhushko not to come” that day, but she did. Not only did she show up, she also broke the school dress code by wearing a vyshyvanka, a traditional Ukrainian embroidered shirt, and asked the mayor what could be perceived as “inconvenient” questions.

“She embodied a mix of gentleness and rebelliousness, romanticism, and an ironic view of the world, with sharp intellect and authenticity,” Hrachova said.

The last work of art Kozhushko shared on her social media was on Aug. 24, Ukraine’s Independence Day. The print, titled “Fight,” depicts a pair of jagged hands raised toward a starburst, at the center of which is the Tryzub, Ukraine’s national symbol depicted on its coat of arms.

A pair of hands reaching for a star was a common motif in Kozhushko’s work, “which characterized her as a big dreamer and a person with a big heart,” according to Avksentieva.

The stark contrast of black ink against a white backdrop evokes a heightened sense of struggle, underscoring the gravity of the stakes. The Tryzub, rendered in white, symbolizes Ukraine’s independence as a virtuous and ultimate goal.

“Aug. 24 has always been an important date and celebration for me, even as a child when I didn’t fully grasp the significance of these numbers,” Kozhushko wrote.

“But now, with a full understanding of our history — both past and present — I am grateful to have been born in this country and thankful to all those who have made it independent today.”

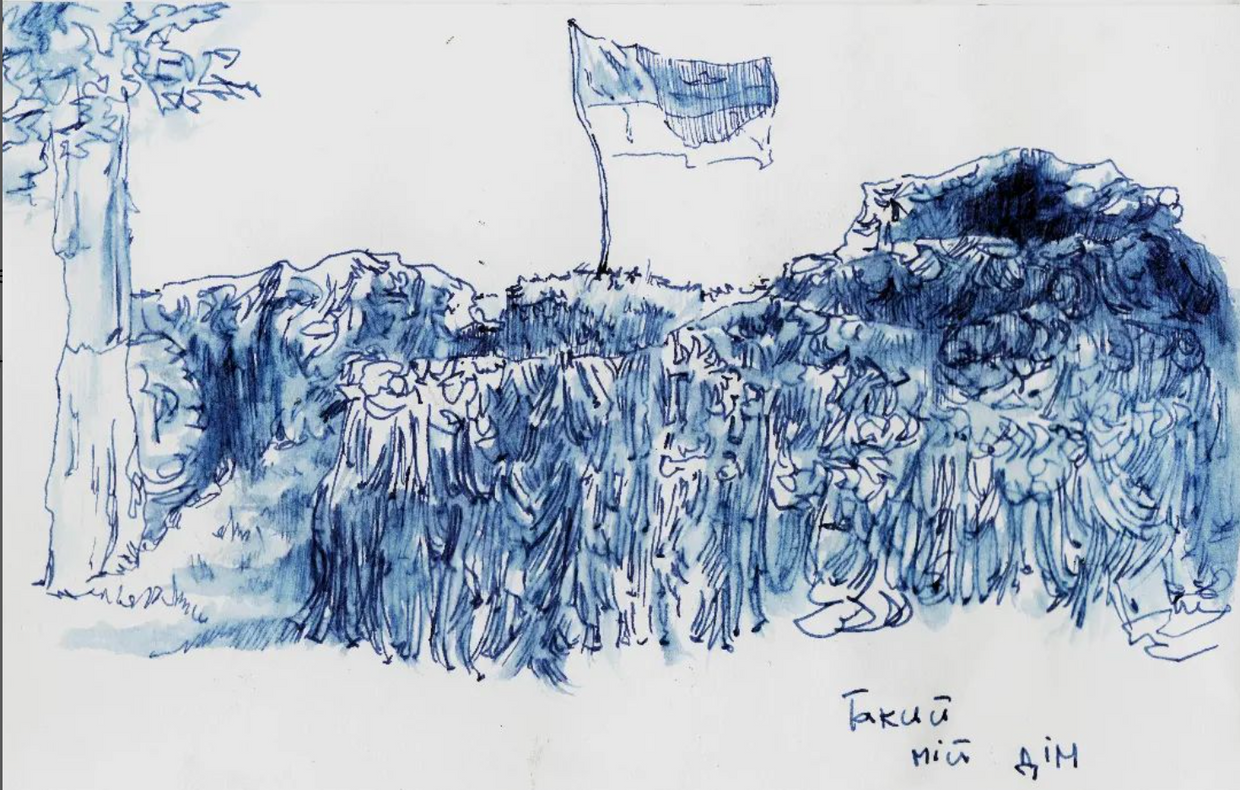

Poet Serhiy Zhadan, who is currently serving in Ukraine’s National Guard, was “a driving force” for young artists like Kuzhushko in Kharkiv, according to several of her friends. He shared a screenshot on his official Facebook page of another drawing that she had sent to him just an hour before her death – her “last ever drawing,” in his words.

In the sketch, a young, nymph-like girl is perched on a tree and looking out into the distance. The composition is almost reminiscent of the sketches made by 19th-century national poet and artist Taras Shevchenko, suggesting that Kuzhushko was always experimenting with different forms of artistic expression.

“The Russians continue to destroy our future,” Zhadan wrote. “There is no explanation for this. And there is no forgiveness either.”

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan, sharing an important culture-related story from Ukraine. It's always emotional to write about cultural figures' lives being killed in Russia's war, but this one was especially difficult. But that's why it's more important than ever to bring attention to who they were and make sure that their memories live on. If you like reading such stories, please consider supporting The Kyiv Independent.