“We are dealing with a powerful state that is pathologically unwilling to let Ukraine go,” President Volodymyr Zelensky tells journalist Simon Shuster on a train from the front line back to Kyiv in 2022. “(Russia sees) the democracy and freedom of Ukraine as a question of their own survival.”

Originally elected in 2019 as a president who would defend the interests of the Ukrainian people against the ruling class, the full-scale Russian invasion thrust Zelensky into the role of a wartime president tasked with ensuring Ukraine’s survival.

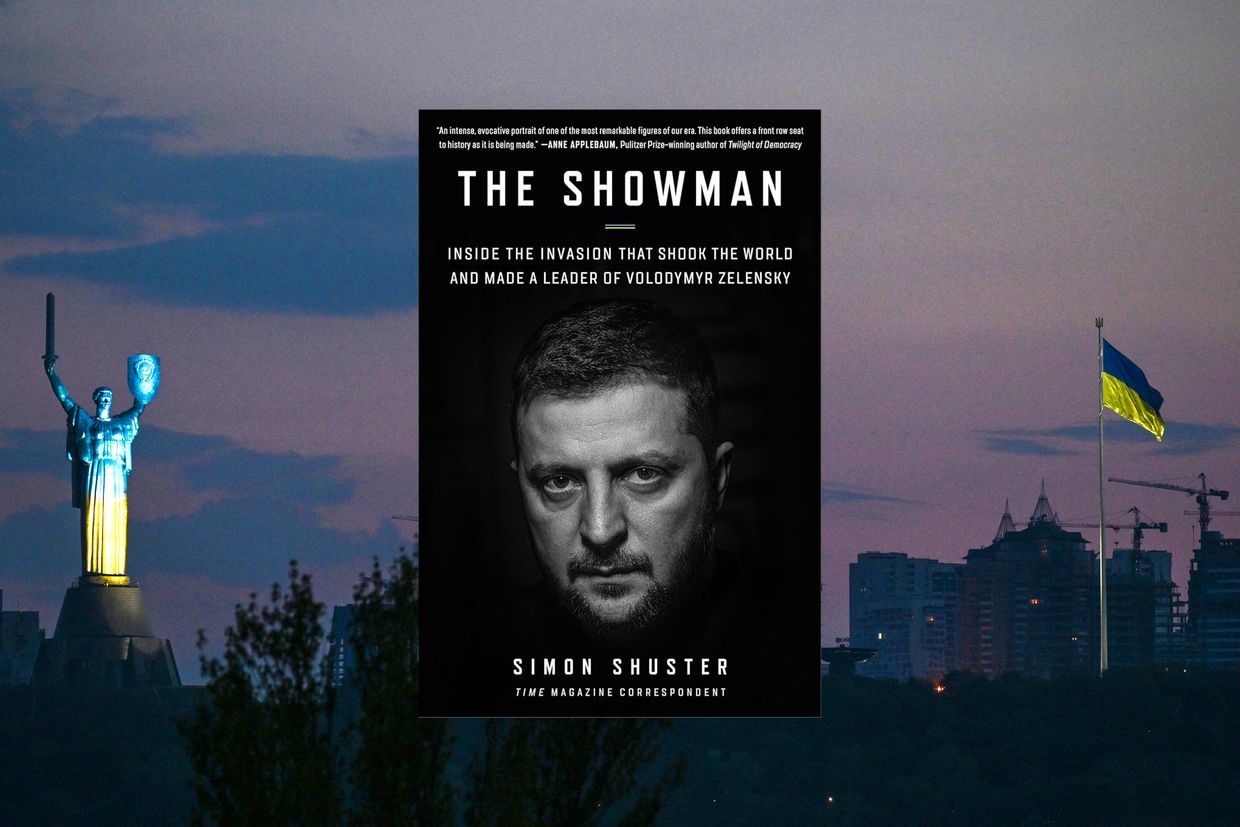

Shuster’s new book “The Showman” covers moments of Zelensky’s life leading up to his presidential run and concludes shortly after the liberation of Kherson in November 2022. Interviewing people close to Zelensky, as well as trailing the president from his office to the front line, Shuster endeavors to portray a figure who has spent his whole life refusing to accept failure — “losing is worse than death,” according to Zelensky — and repeatedly seeks to defy the odds stacked against him.

While "The Showman" offers some intriguing insight to English-language readers about Zelensky’s early career, as well as his evolving sense of national identity over the years, there are questionable elements of the book that detract from its overall value to the expanding collection of literature on Russia's war against Ukraine.

Readers who only started to pay more attention to events in Ukraine after the full-scale invasion will no doubt be taken in by the parts of the book dedicated to Zelensky’s rise to fame as a comedian, given that a language and cultural barrier can prevent them from truly appreciating the impact his comedy shows had on independent Ukraine.

The variety show Evening Kvartal, as Shuster notes, broke the illusion of deference to political figures that was a staple of the Soviet era – nobody was above criticism or downright mockery. But Shuster also takes a look back earlier at the start of Zelensky’s comedy troupe on the KVN competition in Moscow, where “Zelensky came face-to-face with a brand of Russian chauvinism that would, in far uglier form, manifest itself about two decades later in the Russian invasion of Ukraine.”

KVN, otherwise known as “The Club of the Funny and Inventive,” is a famous Russian televised competition in which comedy troupes from across Russia and neighboring countries compete. In the 1990s, it “stood out as a rare institution of culture that bound Moscow” to former Soviet countries and “could be seen as a vehicle for Russian soft power.” Ukrainian comedy troupes like Zelensky’s faced discrimination in Moscow, no matter how genuinely funny they were.

Thanks to his determination and talent, Zelensky enjoyed immense fame in Ukraine and Russia during his entertainment career. But Shuster writes that he was initially hesitant to publicly get involved during the EuroMaidan Revolution in 2013-2014 in the way that other Ukrainian celebrities did, making statements like "We're with the people" when pressed for comment by a journalist.

The EuroMaidan Revolution started when Ukrainians gathered in central Kyiv to protest against pro-Russian President Viktor Yanukovych's decision in November 2013 to abandon signing an association agreement with the European Union, choosing instead to strengthen economic ties with Russia. Nearly 85% of the profits from Zelensky’s media empire came from the Russian market back then, according to Shuster. The revolution was eventually “the main topic on all the biggest talk shows in both Russia and Ukraine,” meaning that Zelensky had to take a more definitive stand on what was happening.

Zelensky chose to sever business ties with the Russian market out of moral principles after the illegal annexation of Crimea and the invasion of Donbas in 2014. This choice is best summarized in one of Zelensky’s last parody news segments in Moscow, cited by Shuster, in which Zelensky stands at the edge of Red Square and declares: “I’m reporting here from the heart of Russia, if it has any heart left at all.”

As the events described in “The Showman” inch further toward the present, issues begin to arise with the use of certain terms that should have already become unacceptable in reporting on Ukraine over the past 10 years of war. There are passages in both “The Showman” and Shuster’s early articles for Time on Russia’s war against Ukraine that tempt sensationalism, sometimes giving the impression that the author is more interested in entertaining than informing the reader. It’s worth revisiting some of his earlier work as it points to the issues with this book.

For example, one of the Time articles from March 2014 that has evoked outrage among Ukrainian readers is titled “Many Ukrainians Want Russia to Invade Ukraine.” In many newsrooms, editors typically have the responsibility of selecting article headlines. Without knowledge of the inner workings of Time's editorial policy, it is not possible to attribute the wording of the headline to Shuster. But the article’s lede immediately establishes a certain tone that is hard to shake for the rest of the article: “To many in Ukraine, a full-scale Russian military invasion would feel like a liberation.”

Shuster acknowledges in that article that “much of” Russia’s coverage portraying the events of the EuroMaidan in Kyiv as “a fascist cabal intent on stripping ethnic Russians of their rights” amounted to “blatant scaremongering” and that unease in southern and eastern Ukraine was “fueled in part by misinformation from Moscow.”

At the same time, he writes that Ukraine’s then interim President and Prime Minister had “given Russia plenty of excuses to accuse them of doing the opposite” of their pledge to guarantee the rights of all ethnic minorities in Ukraine by “revoking the rights of Ukraine’s regions to make Russian an official language alongside Ukrainian.”

There are references abound to the “ethnic Russians” of Ukraine’s east and south in Shuster’s reporting for Time back in 2014. While there was frequent intermingling between Ukrainians and Russians during Soviet times — Shuster himself is the son of a Ukrainian father and a Russian mother — the demographics in those regions were also largely influenced by Soviet authorities orchestrating forced deportations and population resettlements during the first half of the 20th century.

Without any mention of this much-needed historical context, it is too easy for the casual reader to get swept up in the Kremlin’s lies about the “discrimination” against Russian speakers in Ukraine. Likewise, the continued use of terms such as “separatist” in “The Showman” while also writing that Russian special forces were involved in seizing Crimea and parts of Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts might throw off the reader. Unfortunately, there have been local collaborators aiding Russia in its goals to take control of these Ukrainian regions, but conveying any hint of an “organic” separatist movement is a disservice to the reader 10 years on.

The issue of language in Ukraine has been frequently misrepresented over the years by a number of media. Even today, being a predominant Russian speaker in Ukraine is not necessarily an indicator of one’s political loyalties.

One example from November 2023 is the significant backlash that followed when linguist and former lawmaker Iryna Farion declared she couldn't regard Russian-speaking servicemembers in the military as true Ukrainians, resulting in her getting fired from her university post at Lviv Polytechnic University. Even during a full-scale war, when the Russian language has come to be associated by many with the atrocities committed by the Russian military, Ukrainian students were outraged by Farion’s implication and went out in protest to demand her dismissal.

Shuster mostly refrains from indulging in terminology about the so-called divides between Ukraine’s regions in “The Showman.” He rightfully points out how the once famously Russian-speaking Zelensky, who hails from the central Ukrainian city of Kryvyi Rih, “saw the hollowness of (Russia’s) excuse for violence, because he knew there were no threats to his rights as a Russian speaker in Ukraine, certainly none that might require any intervention from the Kremlin.”

Likewise, he acknowledges that Zelensky’s victory in the 2019 presidential election “exposed the hollowness of Putin’s lies about Ukraine” and “it took the victory of a Russian-speaking Jew from Kryvyi Rih to show that Putin’s theories about Ukraine were not only false but ridiculous. In eastern regions that Putin liked to describe as part of the ‘Russian world,’ Zelensky got nearly 90% of the vote.”

The selling point of “The Showman” is that Shuster was granted close access by Zelensky himself, even noting that “some of Zelensky’s aides, in particular the ones responsible for his security, did not always appreciate the access the president gave me, especially on the days when he invited me to travel with him to the front.”

But given Shuster’s close access, as well as his many years spent reporting in both Ukraine and Russia, it is a bit perplexing why he chooses to pass judgment on what are viewed by some as Zelensky’s more controversial decisions during his presidency. The starkest example is the chapter dedicated to former pro-Kremlin lawmaker Viktor Medvedchuk, who posed one of the biggest challenges to Zelensky’s presidency prior to the full-scale invasion.

The Zelensky administration blocked Medvedchuk’s TV channels in 2021 because "the danger from Medvedchuk and his television channels felt existential to Zelensky." Shuster asks him about this decision but writes that Zelensky’s response – how the narratives pushed by Medvedchuk and his circle sought to erode Ukrainian statehood – “stank of paternalism.” “Could people not be trusted to watch TV and form their own opinions?” Shuster wonders.

He goes on to declare that “(Zelensky’s) tactics resembled the ones Putin used in the early 2000s” when he started to go after his most vocal critics and that Zelensky’s rhetoric “seemed out of character” compared to the “soothing tones of the unifier who took office in 2019.”

Russia’s wartime tactics against Ukraine have often been described as “hybrid warfare,” meaning that it employs conventional and nonconventional means of aggression. Information warfare is a large part of that, so one could argue it is not all that shocking for a Ukrainian president to try and prevent an opponent who was so openly pro-Russian from spreading disinformation. To Shuster’s credit, he also includes Zelensly’s rebuttal that the likely sources of financing for these TV channels – that is, Russia – obliged the Ukrainian state to get involved. But his need to question the decision is nonetheless disruptive.

Before Medvedchuk was charged with high treason in 2021, he spent years pushing for closer ties with Russia and making Russian an official state language. Russian dictator Vladimir Putin is also the godfather of Medvedchuk’s daughter, a role that is perceived with a greater sense of responsibility in the Eastern Orthodox Christian faith than in parts of the Western world. Medvedchuk was captured in spring 2022, months after fleeing house arrest, but he was later handed over to Russia during a prisoner exchange that fall.

Zelensky’s previous career as an actor and comedian appeared to put him at a disadvantage not only to his political rivals, especially at the beginning of his term. But his “instincts as an actor came with some advantages. Zelensky was adaptable, trained not to lose his nerve under the glare of a massive audience,” writes Shuster.

At the same time, Zelensky also “showed a painful sensitivity to criticism” and had “an abiding need to be liked and applauded.” His former chief of staff, Andriy Bohdan, claims that he “soon understood the importance of keeping the president away from his accounts on social media” and that “even the comments Zelensky got from strangers could upset him.” This trait could have the potential to stand in the way of effective political leadership, but his ability to thrive in the spotlight has arguably allowed him to persevere when it comes to rallying the world's leaders for much-needed wartime aid.

Some of the tension brought on by Zelensky’s approach to leadership is alluded to in the book, such as the ongoing rumors of his alleged conflict with Ukraine's Commander-in-Chief Valerii Zaluzhnyi. Shuster also allows himself to speculate on the potential challenges facing the president in the future: “I don’t know how Zelensky will handle that fraught transition (after the war’s end and) whether he will have the wisdom and restraint to part with the extraordinary powers granted to him under martial law, or whether he will, like so many leaders through history, find that power too addictive.”

The most sympathetic figure to emerge from the book is ultimately Zelensky’s wife, First Lady Olena Zelenska. From her work alongside Zelensky at their fast-growing TV production company to the initial anger at not being informed of when Zelensky would announce his run for president, uncertainty as to how to fulfill her role as first lady, and quick adaptation to the harsh reality of war, it is clear that she has handled the whirlwind of the past few years with the utmost grace and fortitude. Speaking of her children, she tells Shuster that they “are not as naive as we would like” concerning their understanding of the war. Her desire to preserve their innocence as much as possible during wartime is palpable.

Readers will gain a better perspective of Zelensky in “The Showman,” not just as a wartime leader but as a Ukrainian who came to understand how important it was to embrace his national identity once Russian forces invaded with tanks to destroy it. But Shuster’s tendency to editorialize and underscore his “inside access” diminishes the book’s quality compared to what could have been a strictly journalistic approach. The length of the war remains uncertain, but what’s clear is that the definitive book on Zelensky's presidency has yet to be written.

Note from the author:

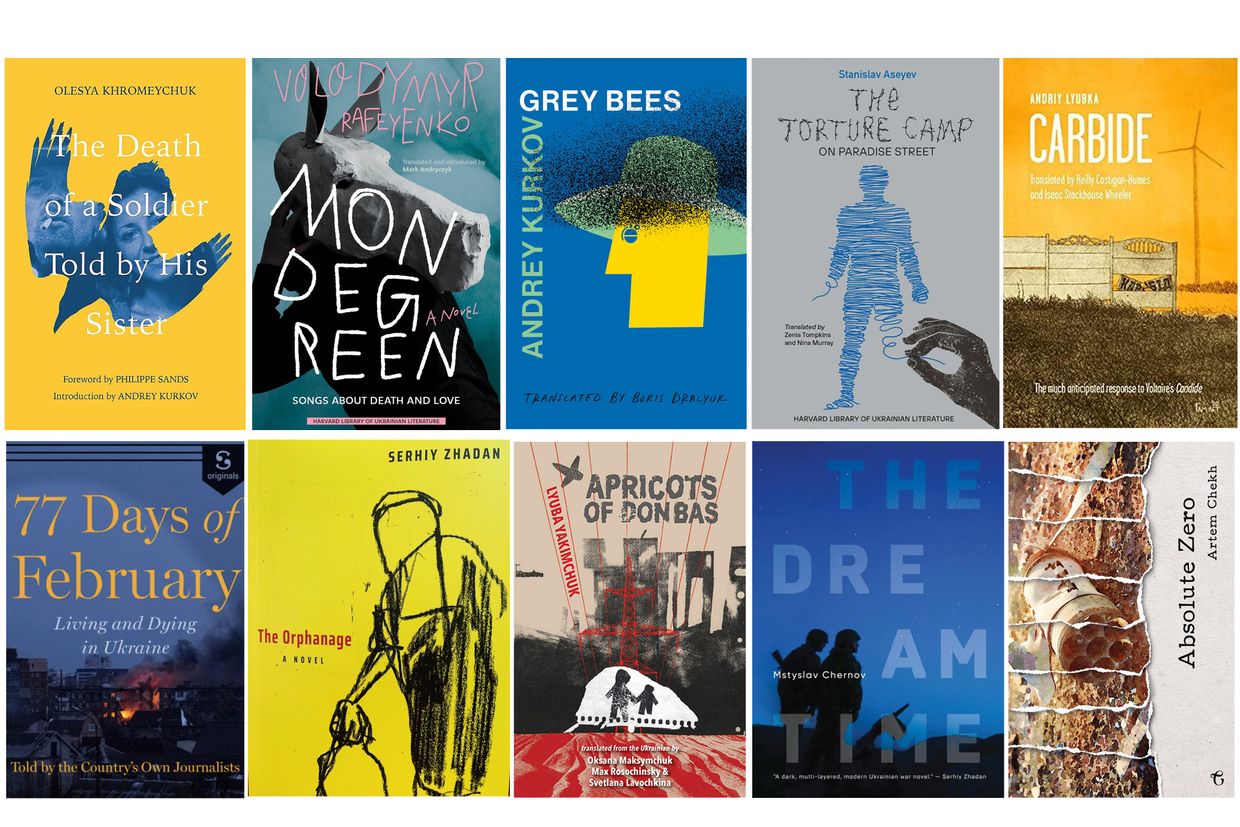

Hi, this is Kate Tsurkan, thanks for reading this article. There is an ever-increasing amount of books about Ukraine available to English-language readers, and I hope my recommendations prove useful when it comes to your next trip to the bookstore. Ukrainian culture has taken on an even more important meaning during wartime, so if you like reading about this sort of thing, please consider supporting The Kyiv Independent.