DONETSK OBLAST – Gasping for air from a trench in eastern Ukraine, an infantryman was ready for the worst when a suffocating white smoke spread into his position.

A Russian drone had just dropped a gas grenade into the trench, an internationally banned practice in warfare used to suffocate Ukrainian soldiers hiding inside. Forced out in the open, the Ukrainians immediately became vulnerable targets for Russian drones and artillery.

“I thought about everything that I should and shouldn’t have thought about,” said Ihor, who recalled the February incident near Chasiv Yar, where he held off Moscow’s troops advancing from the ruins of Russian-occupied Bakhmut. Like some other soldiers who spoke to the Kyiv Independent, he asked not to disclose his identity for security reasons.

Russia has increasingly deployed chemical agents in its grand offensive to occupy the last cities in the Donbas region under Ukrainian control. The suffocation tactic is to take out entrenched personnel and dampen the morale of Ukrainian soldiers who – severely outmanned and outgunned – have been withdrawing village by village in the east for nearly a year.

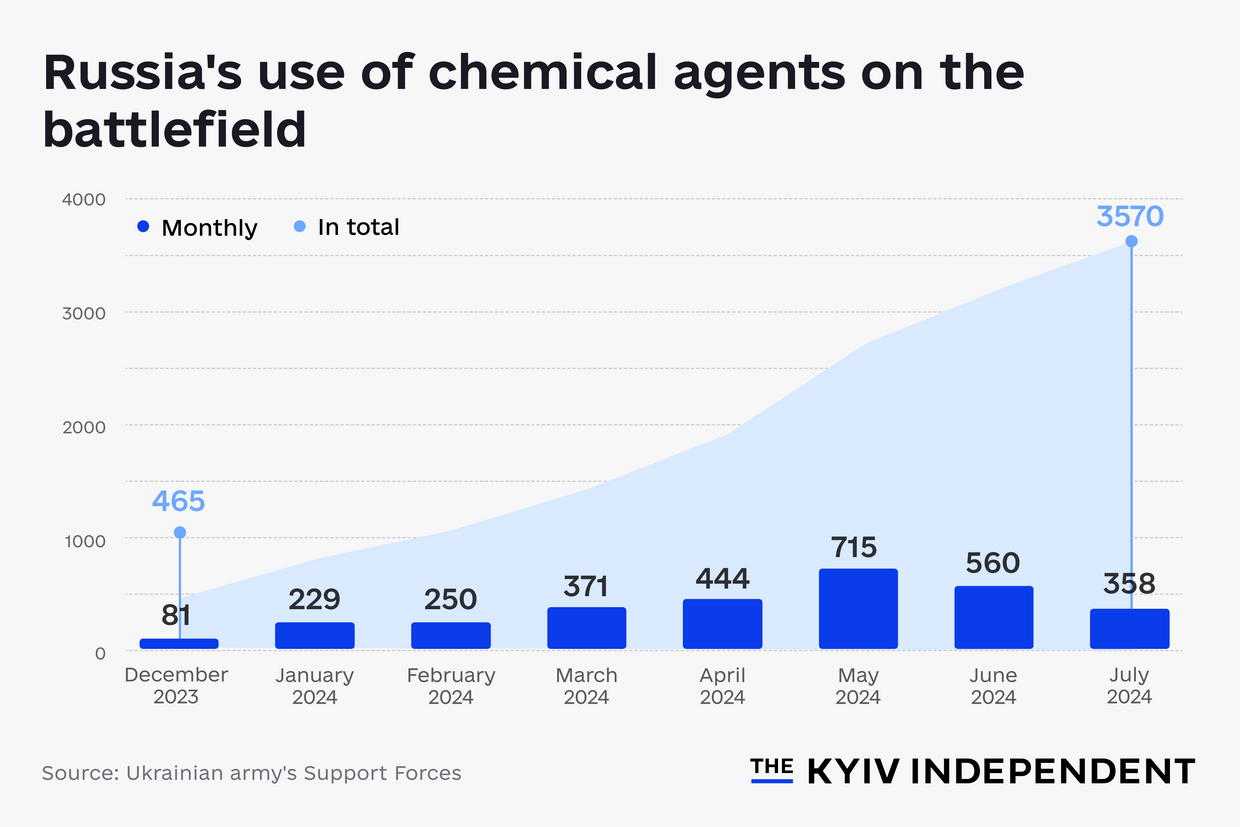

The attack experienced by Ihor occurred as Russia ramped up its illegal use of chemical agents during its full-scale invasion launched 2.5 years ago to over 4,000 officially recorded cases, marking a sharp uptick from about 600 as of January, according to the Ukrainian military.

The soldier said it felt nearly impossible to breathe inside the trench. His lungs felt as though they were burning. Four men were in the position, but only Ihor didn’t have a gas mask because he had given his own to an older comrade. The squad commander covered his mouth with wet tissues and changed them every five minutes.

Another Russian drone was flying above, waiting for the Ukrainians to step out, according to Ihor. About 15 minutes passed before the drone flew away, allowing Ihor’s unit to relocate to a backup dugout.

“Another five minutes (at the trench contaminated with gas) and the lungs would have collapsed,” Ihor said.

The era of modern chemical warfare began in World War I when a stalemate in trench warfare encouraged the use of poisonous gas. The practice was adopted by conflicts that followed, from the Vietnam War to the Syrian Civil War.

In the current war in Ukraine, often referred to as the first drone war, Russia has used UAVs, or unmanned aerial vehicles, to precisely drop gas grenades into the trenches.

For Ihor and his soldiers, waiting at the new hideout was no less daunting. Relentless Russian fire made it dangerous to walk to the nearest evacuation point. They waited a day before seeking medical support.

“I knew that if I slept, I would not wake up,” Ihor said.

Ihor eventually made it to the medics near Chasiv Yar, carried by his comrades since he was no longer able to walk. The gas attack left a permanent mark on his health. He can no longer jog more than 10 meters without running out of breath.

Russia intensifying silent killer tactics

The testimony of the junior sergeant from the 214th Separate Special Battalion OPFOR is among the over 4,000 officially recorded cases where Russia violated the 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention, a post-Cold-War disarmament treaty that bans the use of chemical weapons in war and obliges countries to eliminate them. The United Nations watchdog Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) says that tear gas is “considered chemical weapons if used as a method of warfare.”

Russia’s use of gas attacks is rising. In January, 229 cases were recorded compared to 639 in June and 358 in July, according to the Ukrainian military’s Support Forces, a branch of the army responsible for inspecting chemical warfare.

Ukrainian soldiers and officers interviewed acknowledged that the tactic is effective, allowing Moscow to capture positions occasionally without destroying them.

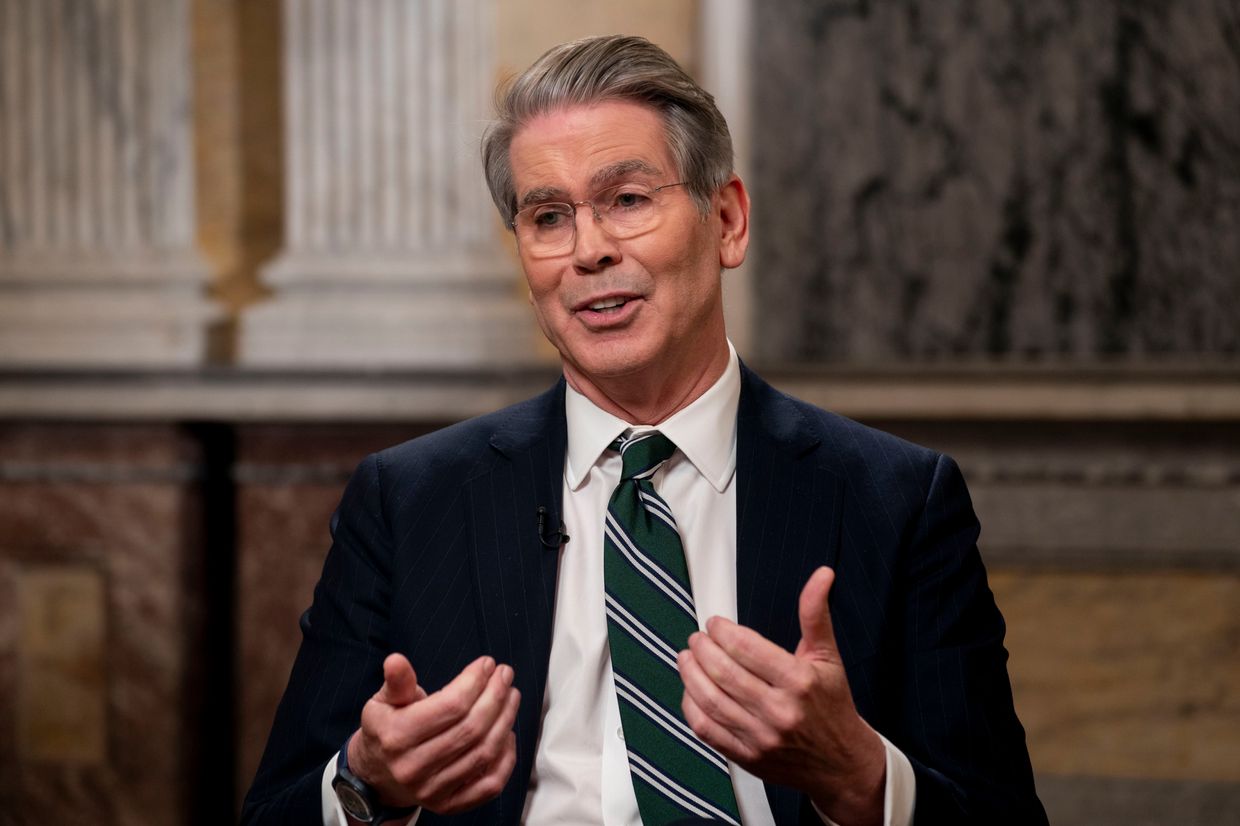

“Your natural reaction is to get the hell out of there because it feels as though you are dying,” said Hamish de Bretton-Gordon, former commanding officer of the U.K.’s Joint Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Regiment.

“And so the guys get out of the trench, and then the Russians immediately follow it up with fire and artillery,” he added, describing the modern era where treacherous illegal weaponry from the past is combined with state-of-the-art killer machines that fly.

The exact number of soldiers who were injured or killed by conventional arms after a gas attack is unknown, but de Bretton-Gordon said he expects it to be “lots.” Concentrations of gas, he added, can remain for as short as a few minutes to as long as half an hour.

Ukraine says about 2,000 soldiers have sought medical care afterward, and at least two are confirmed to have died directly from being poisoned by gas attacks as of July. But scores more could have gone unrecorded, with soldiers being killed or wounded as a result of being disoriented or forced to flee from cover.

Ukrainian Colonel Artem Vlasiuk from the Support Forces’ Radiation, Chemical and Biological Protection Command told the Kyiv Independent that Russian troops are deploying CS and CN tear gasses.

Vlasiuk also said that there were “several cases” of Russian troops using ammonia and chloropicrin gas on the battlefield, with the latter being the most dangerous. The U.S. has accused Russia of deploying chloropicrin, often used in agriculture and widely weaponized as a “vomiting agent” during World War I.

“The use of such chemicals is not an isolated incident, and is probably driven by Russian forces’ desire to dislodge Ukrainian forces from fortified positions and achieve tactical gains on the battlefield,” the U.S. Department of State said in May, asserting that Moscow has violated the Chemical Weapons Convention by deploying riot control agents as a method of warfare.

The statement came as the Department of State imposed sanctions on “three Russian government entities associated with Russia’s chemical and biological weapons programs and four Russian companies that have contributed to such entities.”

Ukrainian soldiers often struggle to identify the gas on the battlefield. Commonly cited symptoms include nausea, vomiting, eye and skin irritations, excessive coughing, chest tightness and suffocation.

“Everything is burning,” 42-year-old infantry Vladyslav Piholenko with the 79th Separate Assault Brigade deployed in Donetsk Oblast said, describing his encounter with gas. “The skin is burning, the nose is burning, throat, lungs.”

Ukraine said it submitted “detailed and factual information about Russia's gross violations of the provisions of the Chemical Weapons Convention” to the OPCW in July.

In a statement, the Ukrainian delegation to the OPCW stressed that Russia has “significantly increased the use of chemical weapons and chemical riot control agents” and “relies heavily” on them on the battlefield. According to the Ukrainian military’s Support Forces, Russia now conducts three times more gas attacks per month than it did at the beginning of the year.

“In combination with other types of weapons, these chemical agents constrain the actions of Ukrainian units during offensive operations” and compromise defense, Ukraine said to OPCW. Soviet-era gas grenades from commonly-used K-51 to RG-Vo and RGR have been found on the battlefield, according to the Ukrainian military.

OPCW said in May that Russia and Ukraine have accused each other of deploying chemical weapons, but “the information provided to the Organization so far by both sides, together with the information available to the Secretariat, is insufficiently substantiated."

Denying the Ukrainian use of chemical weapons, Vlasiuk said the tear gas Russia uses are “dangerous chemical substances that affect the human body and can be used by the enemy for their own purposes to gain an advantage on the field.”

“The purpose is to disable soldiers for a short period of time in order to, roughly speaking, then enter my position and take prisoners of war (POWs), or as Russian troops often do now, destroy the personnel in the position,” Vlasiuk added.

Soldiers’ ignorance in facing ‘silent killer’

Ukrainian soldiers on the ground say that gas is a psychological test, with even seasoned comrades prone to panic.

Officers and infantrymen said that they felt ill-prepared against the Russian gas attacks. Most of the dozens of interviewees across the front said they weren’t given a modern gas mask and were skeptical about the effectiveness of the Soviet-era one widely distributed by the army.

Infantrymen have also argued that it is more practical to bring extra bullets and water instead of a gas mask weighing around a kilogram that may or may not be useful, but is adding weight to gear.

“What do we need gas masks for?” quipped Vasyl, an infantryman with the 53rd Separate Mechanized Brigade in Donetsk Oblast.

Vasyl dismissed the threat of gas attacks compared to the threat of first-person-view (FPV) drones, KAB-guided aerial bombs, artillery, and mortars.

“It’s just extra weight,” Vasyl said of gas masks before hopping on a truck in a front-line town. “We haven’t encountered it yet, so we don’t need it.”

Lack of preparation appears widespread. Multiple soldiers cited incidents in which only a handful of gas masks were available for around 20 people spread across a trench when attacks occurred. Interviewees said they suffered light symptoms because the positions were in an open field, and the gas was quickly blown by the wind.

Gas attacks have a more serious effect when used in small, enclosed spaces, such as small trenches or dugouts. Russia tends to throw gas grenades one after another, purposefully waiting for the effect of the previous gas grenade to run out before throwing in the next one, soldiers say.

Sergeant Vyacheslav, part of the infantry of the 116th Territorial Defense Brigade, said the most terrifying thing about gas attacks is a comrade – or himself – possibly falling into panic.

Vyacheslav said he and his comrades defending the town of Vuhledar have agreed to put away the rifles near the entry of the dugout and lay down together on the floor to avoid a scenario where someone could shoot oneself or run away. Despite the high threat of gas attacks in his area of deployment in Donetsk Oblast, none of them has purchased a mask. He said he would rather save the money for his family. Western-made gas masks typically cost a few hundred dollars.

Knowing what to do when a gas attack happens and having the right equipment is key to avoid causing panic at positions, according to de Bretton-Gordon, the NATO expert on chemical warfare.

“It’s all about knowledge – if you know what to do, then you're less likely to become a casualty,” de Bretton-Gordon said.

“It's a lack of equipment, lack of masks, lack of training, creating a panic, which is exactly what the Russians want.”

Ukrainian soldiers say they can never tell by the sound whether chemical agents were deployed. They can tell when they feel the symptoms or see colored smoke.

“The noise and the impact of artillery and tank fire is unbelievable, whereas gas is a silent killer,” de Bretton-Gordon said. “It's the noise of the battlefield that terrifies people. So if there's no noise, you sort of don't worry, but actually, you need to.”

Vlasiuk, from the Support Forces, said soldiers who don’t know how tear gas works “can react in a way that makes it worse.”

“They can rub their eyes, they can spread panic to neighboring positions, they can leave their own position, thereby showing your silhouette to the enemy, and it will destroy them one way or another with aimed fire,” he added.

Dan Kaszeta, a chemical weapons expert at the London-based Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) think tank who served in the U.S. Army Chemical Corps, said that “it has been a problem in every army for 100 years to get people to take chemical defense seriously.”

Does Ukraine have enough gas masks?

Vlasiuk said Ukraine has received just under 100,000 modern combat gas masks from Western allies since the beginning of the year. Despite many soldiers saying they don’t have a modern gas mask, the officer said there were still about 10-15 percent of the masks provided left in the stocks as of July. They are waiting for requests to be filled by local officers on the front line so they can be delivered, he added.

The U.S. Department of Defense said it provided “a significant number of gas masks and other protective equipment, including hazmat suits, to help protect against potential chemical and biological threats from Russia.”

Vlasiuk denied that Soviet-era masks are widespread, saying that his team is “constantly replenishing” modern masks and that Ukraine no longer distributes its Soviet gear.

Addressing why soldiers are saying they don’t have a modern gas mask, Vlasiuk said, “This is more of an organizational work” at the level of local commanders who are responsible for preparing troops for what’s ahead and making sure they are well-equipped.

“Where will you shoot if your eyes are burning or when you can’t even breathe calmly, and you are coughing all the time?” Vlasiuk said, stressing that “it is necessary to work at the level of squad or platoon commanders” to take gas masks as seriously as helmets and flak jackets.

De Bretton-Gordon said the Ukrainian army needs 300,000 modern masks, lighter and high-grade enough to keep the CS gas out for a prolonged time. Some soldiers said they purchased quality masks or received them from volunteers.

Gas mask urgency mounts in Russia’s Donbas advance

“There's been a stalemate for so long that they're looking for ways to break through it,” de Bretton-Gordon said, referring to Russia’s rising use of chemical agents. “It's exactly the same as trench warfare in World War I.”

“This is a World War I tactic that is being incredibly effective. And it's been effective because, as in World War I, people didn't have gas masks. As soon as people got gas masks in World War I, it was sort of nullified,” he added.

De Bretton-Gordon said, citing members of the Ukrainian army and government, that he believes Kyiv has recently requested gas masks from London and other allies. The Kyiv Independent couldn’t verify the information, with both the U.K. Defense Ministry and the U.S. Department of Defense declining to comment for operational reasons. The U.K. Defense Ministry told the Kyiv Independent that it had provided over 8,500 to Ukraine since the beginning of the full-scale invasion.

Several higher-ranked officers said that what makes the soldiers more vulnerable is the lack of time for preparation. They explained that in an ideal situation, soldiers would already have muscle memory of putting on gas masks during the recruitment phase and have time for preparatory training during breaks. But in reality, the training is often poor, and recruits arrive too often not knowing how to shoot correctly. The soldiers serving for longer are also too exhausted to bother learning about gas during their short breaks, the interviewees added.

RUSI expert Kaszeta said what is far more dangerous is when a burning tear gas lands near plastics, rubbers, and modern synthetic materials and catches on fire, releasing "a whole mix of really dangerous stuff."

Oleksandr, part of the infantry with the 17th Tank Brigade, recalls having to flee an observation position once near Chasiv Yar because a diesel generator caught on fire after Russian troops threw a gas grenade. The old Soviet-era mask didn’t help. The unknown chemical agent that mixed in the air with diesel was suffocating, he said.

Authorities have reported only two official deaths caused by gas, but the actual toll may be higher. Retrieving bodies for forensic studies is often complicated, especially in situations where troops face encirclement.

Recalling the death of his comrade that went unrecorded, Mykhailo, a captain from a mechanized battalion deployed on the Pokrovsk front, recounted a situation where his group of soldiers were in a bunker surrounded by advancing Russian troops. One of the three guys at the position died after his heart stopped following a gas attack, he said. But the body could not be pulled out to be examined.

“The guys sat there for two days (after the death of a soldier in his early 40s),” Mykhailo said.

Similarly to many infantry positions in the Pokrovsk, Mariinka and Vuhledar sectors in the central part of Donetsk Oblast where Ukrainian forces are facing a grinding Russian advance, Mykhailo said that his soldiers suffered six gas attacks daily, usually two to three attacks within an hour.

Mykhailo’s soldiers were attacked by a combination of gas grenades and FPV drones. Eyewitnesses and victims have said soldiers with previous health conditions or who are older have a higher chance of suffering serious consequences. The Ukrainian army is heavily represented by men over the age of 40.

Former British Colonel de Bretton-Gordon said the West must hold Russia accountable for committing war crimes and help Ukraine with countermeasures, such as through the provision of modern gas masks.

“(Russian troops are) looking at ways to break through and, this year, gas has been in it,” de Bretton-Gordon said. “Whenever the enemy uses a new method of fighting, it's effective until you finally find the countermeasures to counter it.”

“The concern is (Russia) might escalate to more deadly chemical weapons, which is why it's so important that the international community calls them out on it.”

______________________________________________________

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Asami Terajima, the author of this article.

Thank you for reading our story. After months of work across the eastern front and in Kyiv, I'm happy to see the article finally published. Just like many soldiers on the front line, it's easy to dismiss the threat of gas attacks when under much deadlier FPV-drone, artillery and KAB-guided aerial bombs daily, but I felt it was a very important topic. The unpreparedness of the Ukrainian military toward gas attacks had to be raised – to save more soldiers' lives.

To help the Kyiv Independent tell more stories that would otherwise not be told, please consider supporting us by becoming our member.