The European Commission’s historic decision on Nov. 8 recommending formal talks on Ukraine’s EU membership may be a milestone, but political hurdles, reforms, and years of negotiations still await before the country can finally join.

After applying for EU membership on Feb. 28, 2022, just four days after the beginning of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine received candidate status in June of that year.

Since then, the country has embarked on a reform path in hopes of opening negotiations to join the bloc. In its report published yesterday, the commission said that Ukraine had completed enough of the steps laid out in seven recommendations it received from the EU last year.

“It is possibly the most important political decision related to this stage of Ukraine’s membership in the EU,” Deputy Prime Minister for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration of Ukraine Olha Stefanishyna told reporters at a press conference in Kyiv on Nov. 9.

Consensus from 27 members at a European Council summit in December will be required to back the recommendations and begin negotiations.

In the meantime, Ukraine will have to make more progress in anti-corruption and anti-oligarch legislation, in addition to amendments to a law on national minorities.

The homework on remaining reforms in the report, however, does not have “any connection” with a decision in December, according to Stefanishyna.

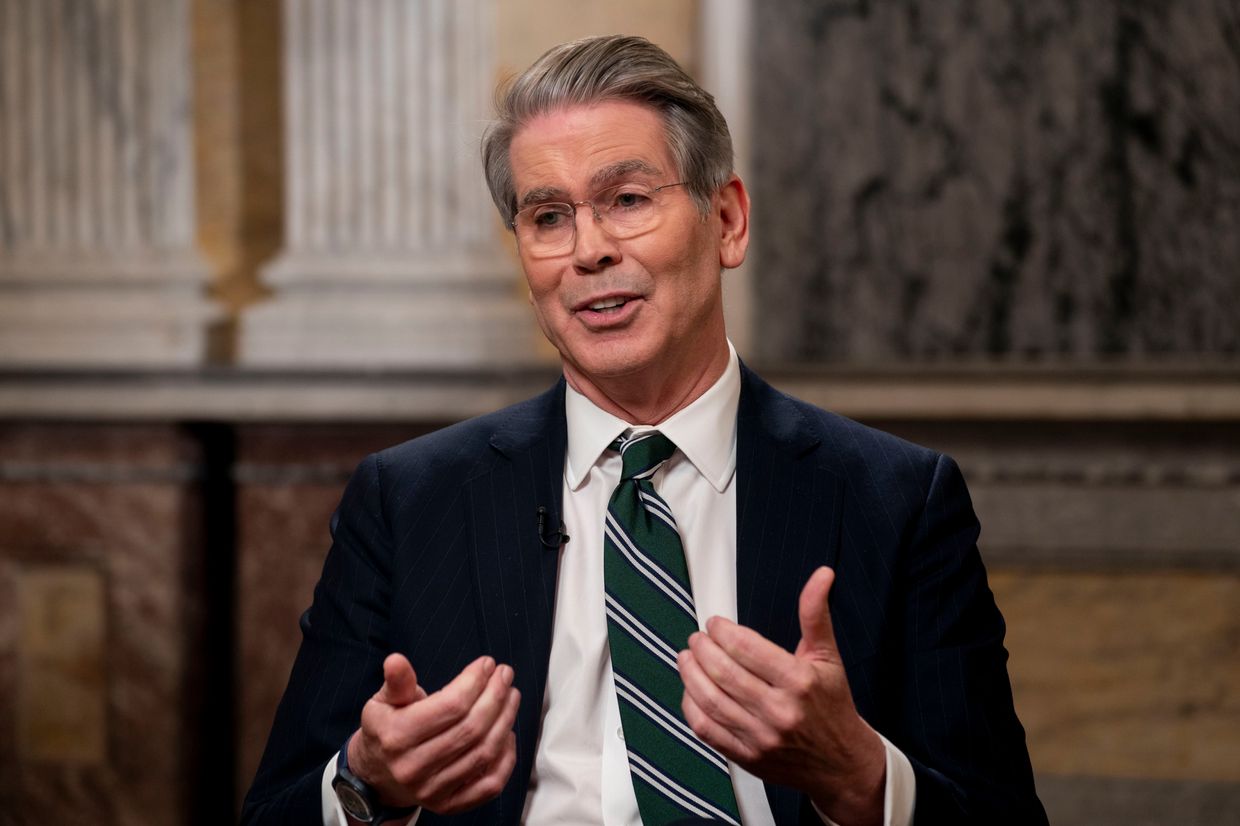

Speaking alongside Stefanishyna, EU Ambassador to Ukraine Katarina Mathernova, confirmed this assessment, saying, “There is no asterisk and no qualification on the recommendation to open negotiations.”

In an early November visit to Kyiv, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen сalled the breadth and depth of the reforms passed during the war “astonishing” and expressed confidence in opening the negotiations process this year.

“You can make it. And you can make it swiftly. You have already completed way over 90%,” said von der Leyen.

Hurdles to come

European leaders will decide whether to back the recommendation at the meeting of the European Council next month. The political decision will require unanimous support.

Hungary has already signaled its hesitation.

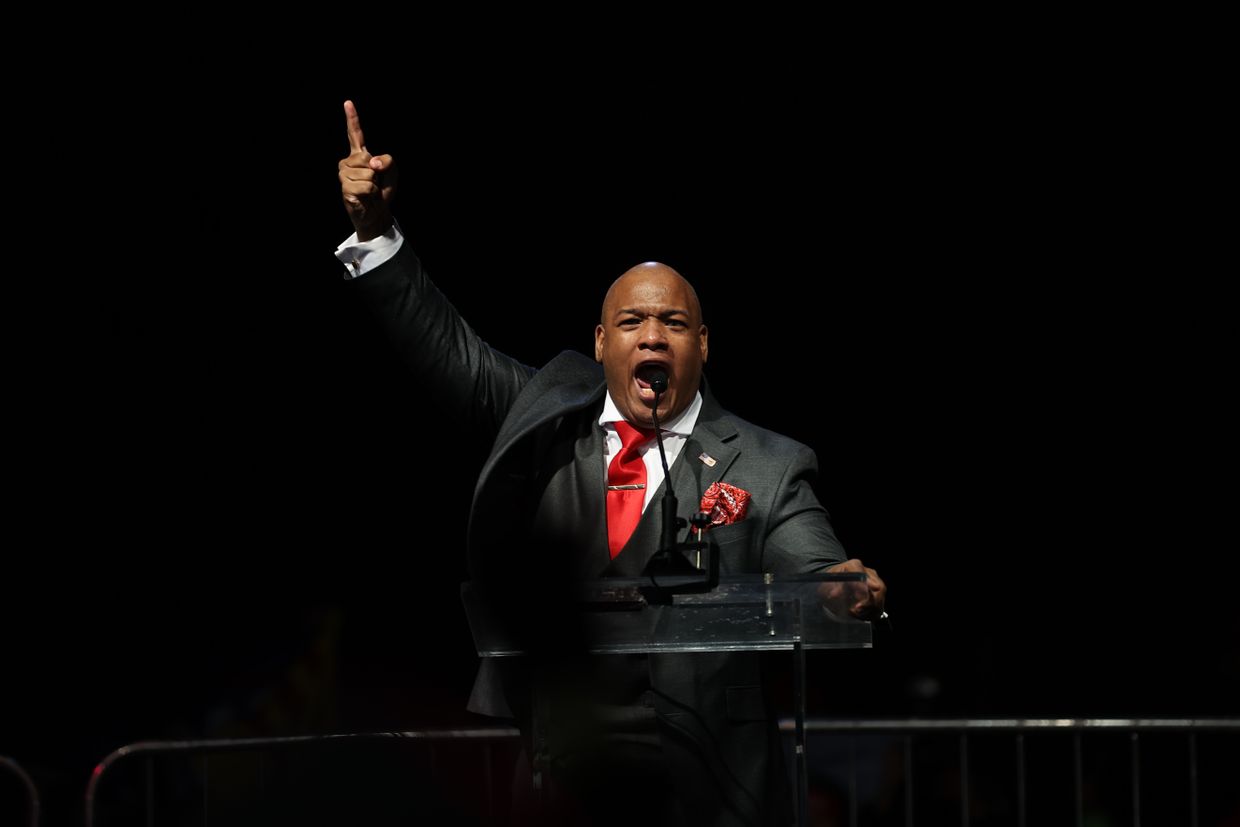

Following the report’s release, Hungarian Foreign Minister Peter Szijjarto said that Ukraine is not ready for EU membership, reiterating Hungary’s concerns over a national minorities law that the country claims infringes upon the rights of Hungarian speakers in western Ukraine.

Russia has repeatedly justified its aggression against Ukraine under the baseless pretext of protecting Russian speakers in Ukraine.

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban was recently the only European leader to attend the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, where he met with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Szijjarto also said that allowing Ukraine to enter would bring war to the EU, despite the fact that a timeline for Ukraine’s admission into the bloc has not yet been established, with EU officials saying negotiations could last years.

The law outlining the rights and obligations of the national minority communities in Ukraine is a part of the seven criteria Ukraine received along with its candidate status.

The November report calls for Ukraine to amend the law again and implement the latest round of feedback from the Venice Commission, which provides advice on European legal standards. The key recommendations concern education, provision of election materials in both Ukrainian and minority languages, and guarantees for the right to use their own language in mass media.

Earlier this week, Balazs Orban, political director to the Hungarian prime minister, vowed to block the opening of the negotiations if the law is not amended.

Stefanishyna said Kyiv contacted Budapest to resolve the issue of language education of the Hungarian minority in Ukraine and provided a roadmap for the process.

“I don’t want Hungary to become a topic in the questions of enlargement on principle because I am confident that we can overcome this challenge, too,” said Stefanishyna.

Despite the potential hurdle, Vadym Halaychuk, deputy chair of the parliamentary committee on EU integration, said that based on preliminary feedback, he is optimistic about the December decision in an interview with the Kyiv Independent.

But the decision will not be the last hurdle. “On the way to membership, the bloc’s member states will have around 100 chances to block the decision on Ukraine’s membership,” said Stefanishyna, citing Mathernova’s estimates on the path ahead.

Grueling enlargement process

The war in Ukraine has foregrounded the bloc’s expansion as a “strong anchor for peace” and a strategic priority, according to its official communications.

But the timeline for internal EU reforms, as well as Ukraine’s negotiations, is challenging to pin down.

“The enlargement process is not physics; there are no mathematical formulas that guide it,” said Mathernova. “There is nothing usual when it comes to Ukraine and enlargement. You are breaking any and all records.”

The process will depend on the political will and speed of the reforms undertaken by the parties.

If the Council green lights the next step, Ukraine will have to align its legislation with 35 different areas of European Union law. In parallel, the EU will work on preparing its institutions to accommodate the potential expansion.

Speaking of the uphill battle facing Ukraine’s parliament, Mathernova said, “They don’t know what is going to hit them once the negotiations open because the amount of … the body of laws and norms that the EU is bound together with is huge.”

Halaychuk said the parliament is ready to take on the challenge with a good understanding of the priorities and no time to waste.

“Delaying the process is not in our interest,” said Halaychuk. “(The negotiation) will require an updated agenda and an updated approach to implementing this agenda.”

Stefanyshina said Ukraine could realistically complete its homework in two years after negotiations begin under the current pace of the reforms.

“It’s important to have high ambitions and strive for it,” Mathernova said.