Kyiv’s efforts to secure as many resources as possible from Western allies to tip the scale of Russia's war in its favor will face a critical moment next weekend as leaders of more than 50 countries meet for the final talks on arming Ukraine before the upcoming U.S. elections.

“This will be a special Ramstein,” President Volodymyr Zelensky said in a video message this past week after returning from his U.S. trip, where he presented Ukraine’s “victory plan” to end the war. Zelensky said Kyiv expects “concrete actions” from its allies at the Oct. 12 Ukraine Defense Contact Group gathering at Ramstein Air Base in Germany, which gathers countries almost monthly to agree upon support for Ukraine and will this time be convened by U.S. President Joe Biden.

Among those actions is the lifting of restrictions on using Western-provided missiles and other weapons to strike targets deep in Russia — so far, a red line the U.S. and other allies have been unwilling to cross, fearing escalation.

Outmanned and outgunned on the battlefield, Ukraine hopes lifting the ban would be a wild card that could help it strike Russian military targets in the rear and, ultimately, grind down its combat capabilities from afar.

As Kyiv pushes for further support, signs are emerging that Russia — two and a half years into its full-scale invasion — may be gradually exhausting its enormous Soviet-era arsenal. Western and Ukrainian analysts expect Moscow to struggle to conduct further high-loss offensive operations in the second half of 2025.

Experts say Moscow has increasingly begun pulling out older and less favorable models – a sign that it could be reaching closer to the bottom of the stockpile. But for now, time is still on Russia’s side.

“Ukraine needs to strengthen its positions on the front line so that we can increase pressure on Russia for the sake of fair, real diplomacy,” Zelensky said at an Oct. 3 press conference during the visit of newly-appointed NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte to Kyiv.

“This is why we need a sufficient quantity and quality of long-range weapons, the provision of which, in my opinion, is being delayed by our partners,” Zelensky added.

Striking ‘the heart of military-industrial complex’

It is unrealistic for Ukraine to come close to Russia in terms of quantity of manpower, so the prevailing strategy is disrupting enemy logistics and striking the “heart of the military-industrial complex” in the rears, according to Dmytro Zhmaylo, co-founder and executive director of the Kyiv-based think tank Ukrainian Security and Cooperation Center.

While Ukraine continues to hold a patch of Russia’s Kursk Oblast captured during a surprise incursion two months ago, Russian troops continue their grinding advance in the eastern Donetsk Oblast, capturing the mining town of Vuhledar this past week.

Ukraine needs to rely on "non-standard" tactics, including long-range strikes, to gain the upper hand against Russia on the battlefield, Zhmaylo said. Ukraine used such tactics using Western weaponry for long-range artillery and rocket strikes to push out Russian troops from parts of Kherson and Kharkiv oblasts by destroying warehouses and logistic routes for months during the autumn 2022 counteroffensive.

Now, Ukraine is deploying its homemade long-range, domestically-developed drones to strike targets as far as over 1,000 kilometers deep inside Russia.

The effects have already been felt in Russia.

In September, Ukraine’s military said it had struck the Tikhoretsk arms depot in Russia’s southwestern Krasnodar Krai, which it called one of the three largest Russian ammunition storage sites key to the Russian military's logistics.

The U.K. Defense Ministry confirmed the Ukrainian Sept. 20-21 overnight drone strike on the Tikhoretsk ammunition depot and another site in Tver Oblast deeper into Russia, as well as another Sept. 18 attack in Tver Oblast that "almost certainly destroyed at least 30,000 tons of ammunition in open and bunker storage."

“The strikes will almost certainly cause, at a minimum, short-term disruption to Russian artillery and small arms munitions supplies, critical resources in a war of attrition dominated by mass fires,” the U.K. Defense Ministry said.

In an attempt to showcase Ukraine’s ability to strike Russian territory, Zelensky has stressed that precise long-range Western weapons could inflict much more damage — and that drones “still do not have enough range.”

Zhmaylo said that if there is enough Western support and long-range strikes are permitted, “only a few months” is needed for the damage to be felt on the battlefield.

“If it’s only drones, then we may not feel it on the battlefield because, during this time, Russia will simply sign more contracts, more echelons (carrying resources) will arrive, and the damage may not be so noticeable,” Zhmaylo said.

Unsustainable Russian losses

Experts interviewed by the Kyiv Independent say that Russia’s current pace of losses — often disproportionate to the limited gains attained — doesn’t appear sustainable, even if Moscow continues to hold the initiative across most of the front line in Ukraine's eastern Donbas region.

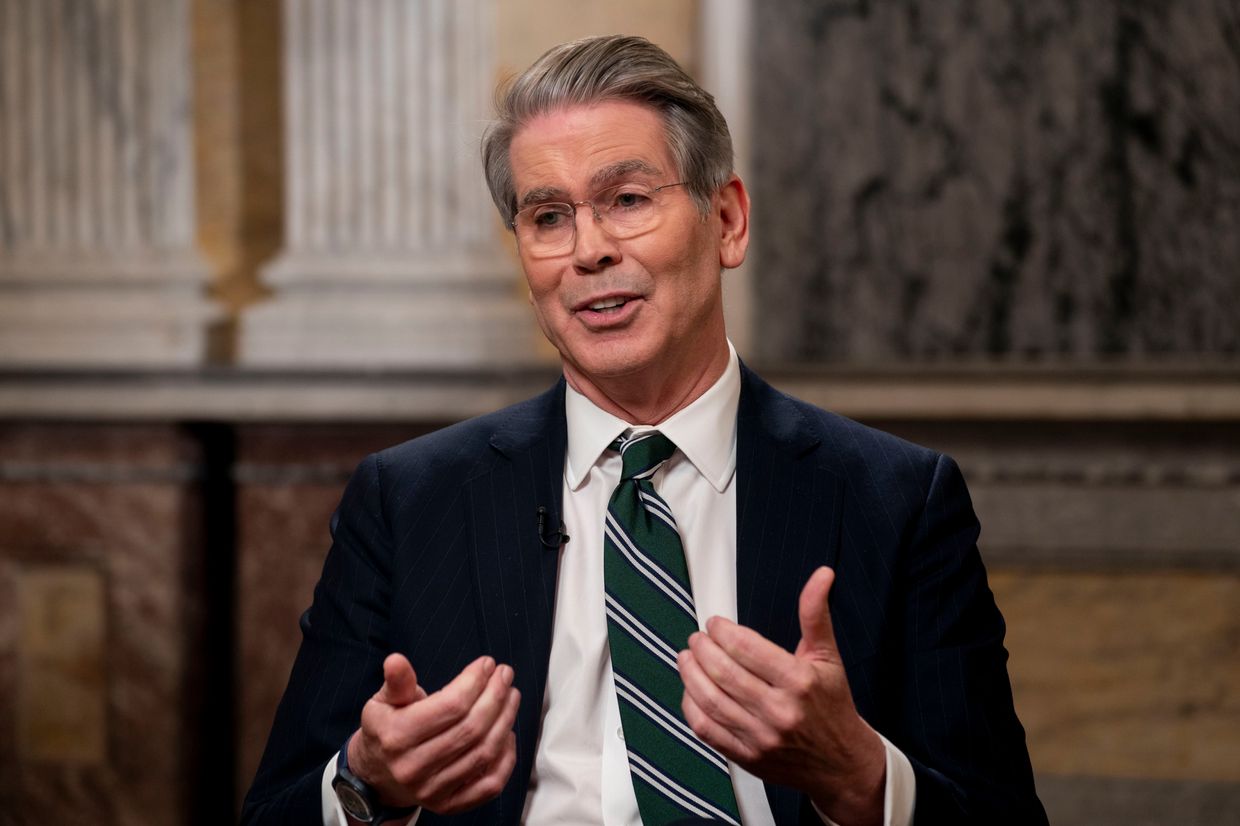

“I expect Russia will experience serious shortages toward the end of 2025 and especially in 2026, assuming the war continues that long,” said John Hardie, deputy director of the Russia Program at the Washington-based think tank Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD).

But Hardie expects Russia to maintain the current offensive pace “at least through this autumn.”

According to a February report by the London-based defense think tank Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), Russia had about 4,780 barrel artillery pieces, 1,130 Multiple Launch Rocket Systems, 2,060 tanks, 7,080 other armored fighting vehicles, 290 helicopters, and 310 fighter jets.

Having lost thousands of tanks and armored vehicles, the analysts are skeptical about whether the Russian arms manufacturing machine can keep up with the pace as the Soviet stocks slowly drain out. Highlighting Russia's domestic weaponry limitations, the country has stepped up supplies of ballistic missiles from North Korea and Iran. Russia has been heavily dependent on Iranian kamikaze drones of the Shahid type for air strikes during its invasion and, more recently, on North Korean artillery ammunition.

Moscow has switched to small assault groups rather than battalions that rely more on human resources rather than equipment, according to military experts who spoke to the Kyiv Independent. This appears to be a sign of gradual resource depletion.

Hardie said coordinating attacks above the company level, which typically consists of roughly 100 men in Ukraine, remains a challenge for both sides.

“If this war were to continue for several years, we will eventually come to a point where Russia won't be just able to keep taking stuff from the storages,” said Pasi Paroinen, an analyst with the Black Bird Group, a Finland-based organization that monitors the war in Ukraine with satellite imagery and social media.

The Russian arsenal is generally divided into two categories: equipment "resurrected from the long-term storage," such as "very old tanks and artillery pieces” from World War II, and brand new or recently upgraded equipment that is more modern, according to Paroinen.

Russia is losing three times more equipment than Ukraine on average, “steadily draining its stockpiles of inherited Soviet equipment with its production, just like in the case of Ukraine, covering only a small fraction of what they are losing,” said Prague-based analyst Jakub Janovsky, who works at the Dutch open-source intelligence monitoring site Oryx.

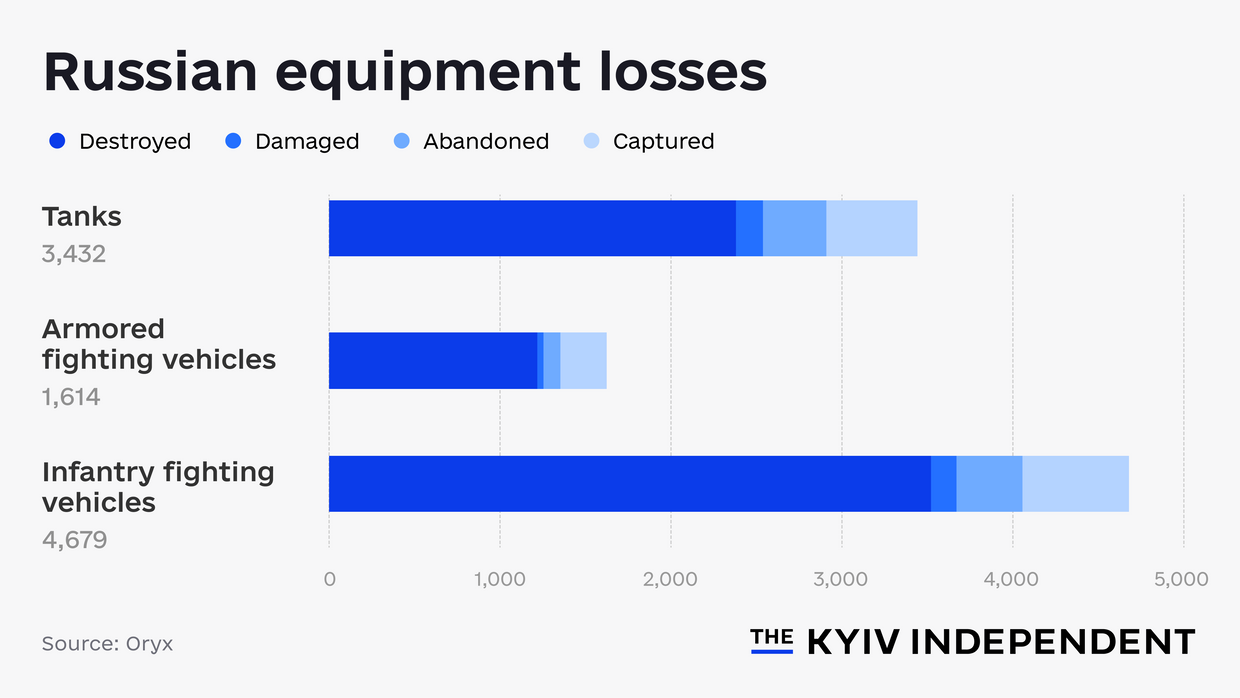

Over two and a half years of full-scale war, Russia has lost at least 3,432 tanks, 1,624 other armored fighting vehicles, and 4,679 infantry fighting vehicles as of early October, Oryx reported, citing what it visually confirmed independently.

Janovsky said Ukraine has been claiming a much higher destruction rate of Russian artillery since last year, and “if a substantial percentage of those claims is true, Ukraine is likely to overtake or significantly reduce the Russian advance in this regard.” But he stressed that the artillery loss is difficult to visually confirm independently, and it is unclear whether Ukraine is counting light mortars as part of its triumph.

“If the war continues at approximately current intensity and rate of losses, it's entirely possible that at some point next year, Russia might either lose or have significantly degraded ability to conduct mechanized offensives because so many tanks, infantry fighting vehicle, etc. will be lost,” Janovsky said.

According to Janovsky, as the quality of Russia’s Soviet-era stocks decreases, the closer they reach the bottom of its arsenal, they become easier targets for Ukrainian artillery or drone fire. The outdated equipment lacks features such as thermal sight and is more vulnerable to mechanical failures.

As Russia slowly drains its massive Soviet-era stocks, Ukraine has been receiving from Western allies more advanced weapons and equipment — though limited in numbers and often with long delivery times.

Just before Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022, Western allies flooded Ukraine’s army with hand-held anti-tank busters, including the U.S. Javelins and Stinger air defense systems, to target Russian helicopters and low-flying jets.

After Ukraine’s forces successfully used the kit to repel Russia’s attempt to seize Kyiv, allies gradually stepped up the firepower provided to Ukraine: first with NATO-grade artillery, later with multiple launch rocket systems such as the U.S.-made HIMARS. Later, from 2023 into 2024, they supplied tanks, long-range Storm Shadow cruise missiles, ATACMS missiles, and, most recently, batches of F-16 fighter jets that started arriving this summer.

Janovsky stressed that “the current level of support is for Ukraine to defend territory, but not much more.”

Time on Russia’s side

As Ukrainian troops struggle to hold the frontlines in the far eastern Donbas region, “the biggest unknown” affecting the war's outcome is the future depth of Western military aid, Janovsky said.

Questions loom about whether Kyiv’s backers will give Ukraine enough to win the war, possibly by forcing Russia into fair peace talks that Zelensky says his “victory plan” aims to achieve or continue a drip-feed approach that keeps its forces in the fight but unable to liberate some 20% of territory still occupied by Russia.

Much depends on the results of the 2024 U.S. presidential elections, experts added. Both presidential candidates remain vague on their Ukraine policy, with Republican candidate Donald Trump skeptical about further U.S. support for Kyiv and Vice President Kamala Harris on the Democratic ticket not addressing it in detail.

Some analysts — and Ukrainian soldiers alike — are more worried about Ukraine running out of resources faster than Russia, which had years to prepare a powerful war machine.

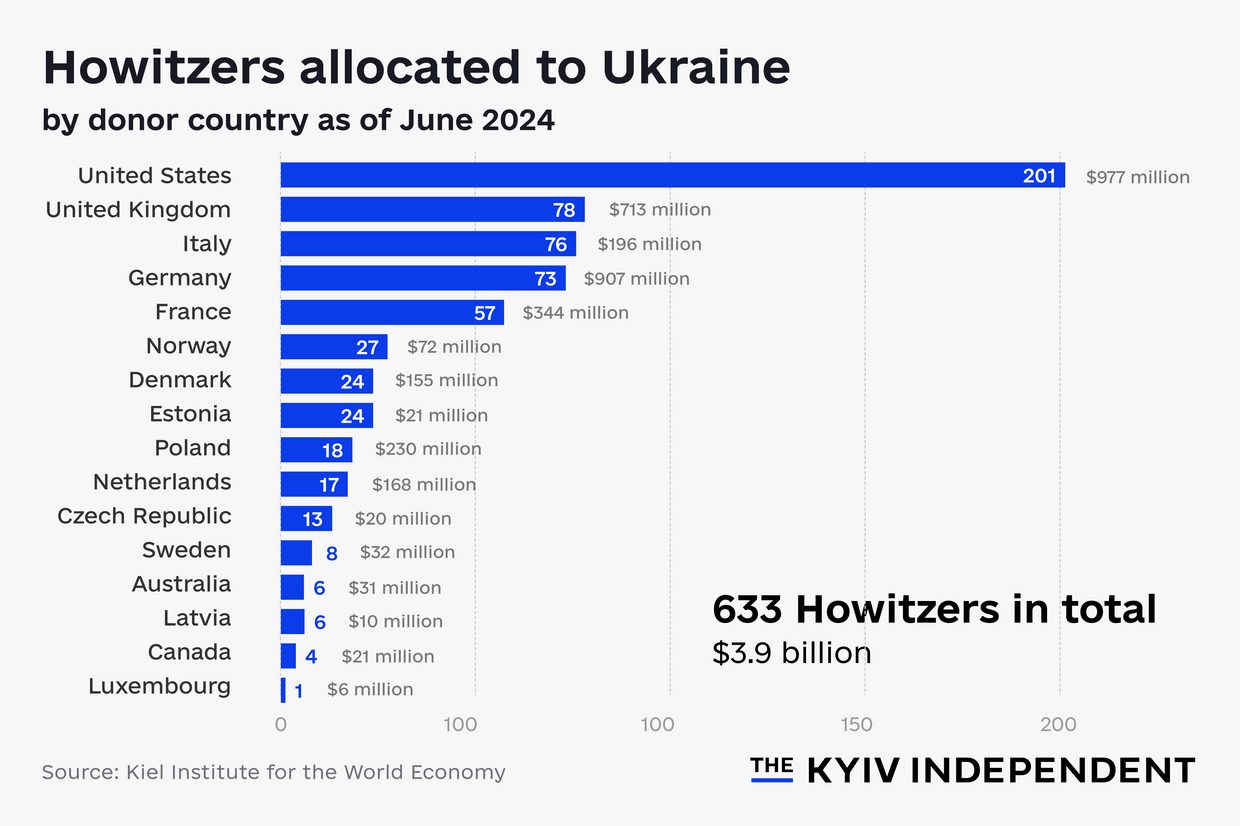

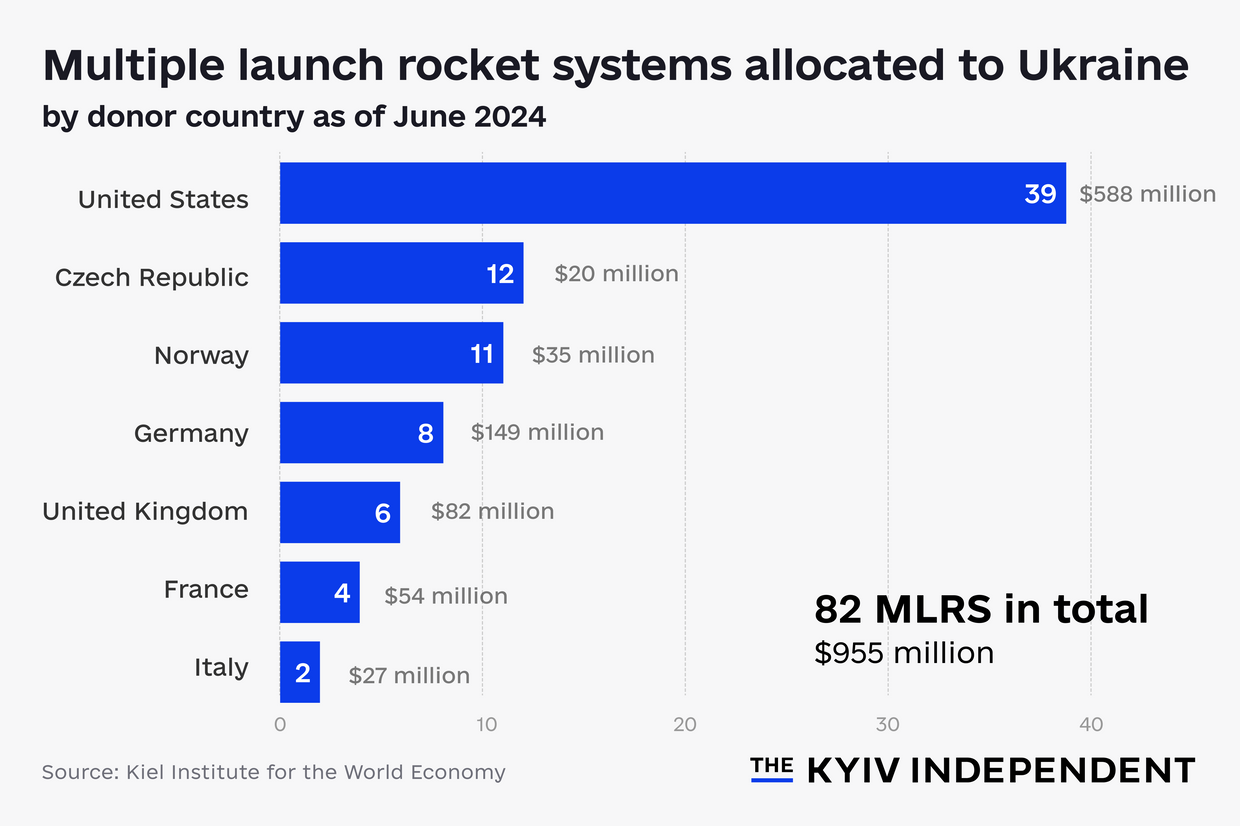

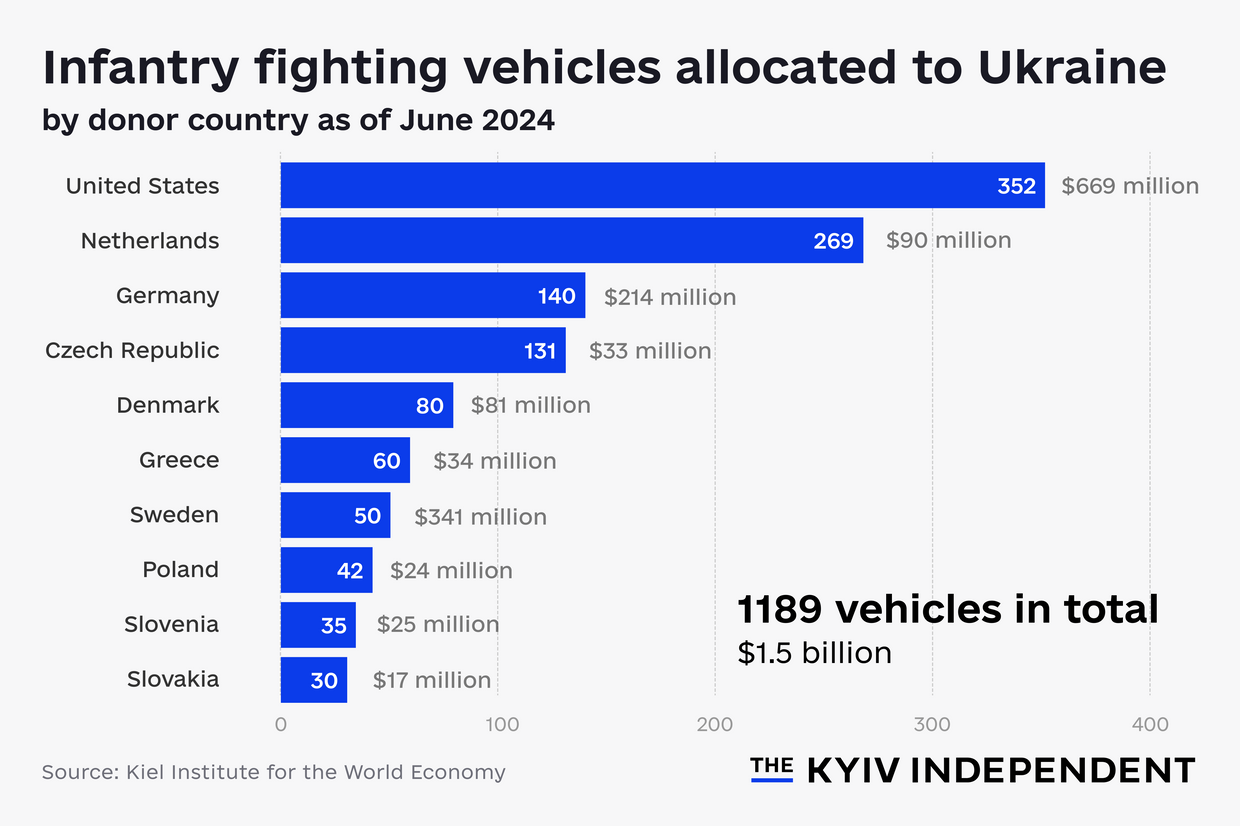

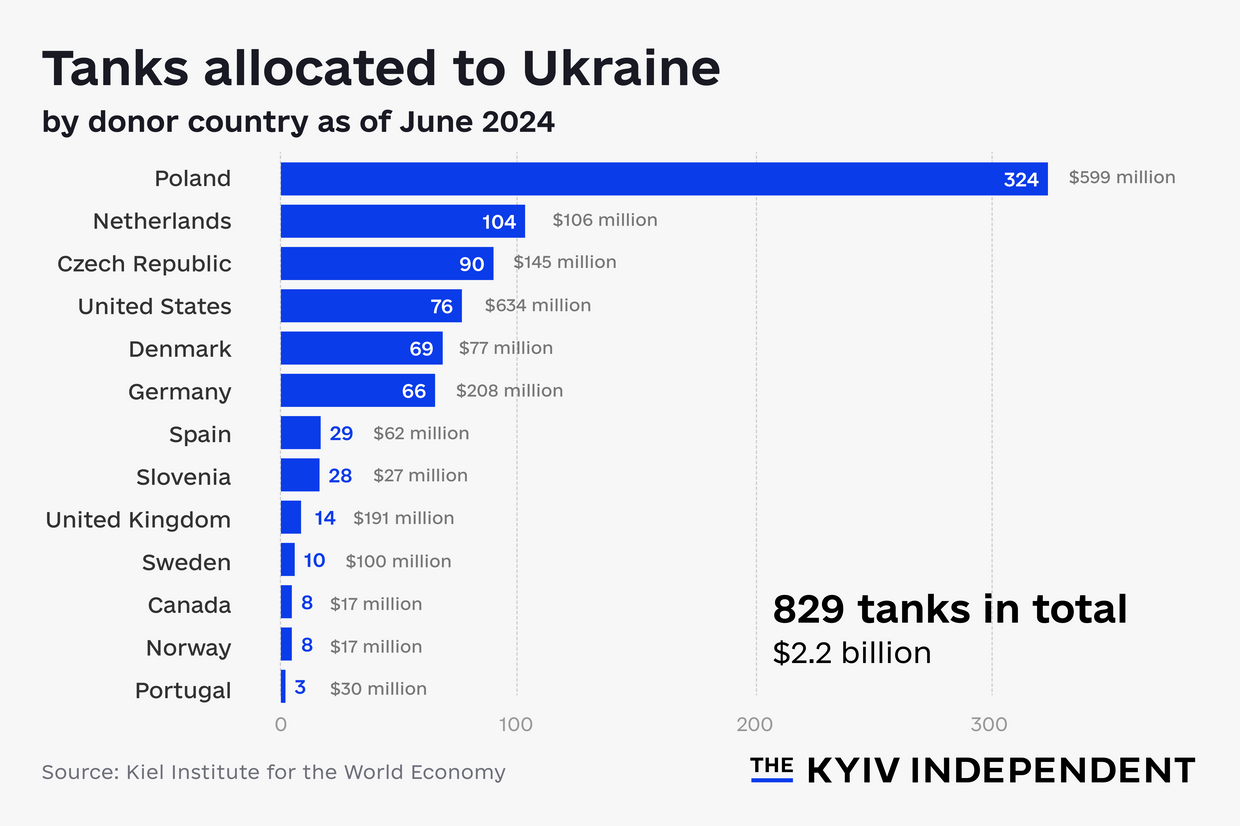

Western nations have provided Ukraine with over 820 tanks, over 1,180 infantry fighting vehicles, over 630 howitzers, and over 80 multiple-launch rocket systems as of June 2024, according to the think tank IfW Kiel Institute for the World Economy, which tracks Ukraine aid. The Ukrainian military needs much more weapons, as they are quickly depleted by Russian fire.

In a rare example of publicly admitting shortcomings in September, Zelensky said Ukraine didn't receive enough Western military aid to equip "even four out of 14" new Ukrainian brigades needed.

Speaking to the Financial Times after his exit, former NATO military alliance Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg acknowledged that he and all allies need to take responsibility for not giving enough weapons to Ukraine when it needed them the most.

“If there’s anything I in a way regret and see much more clearly now is that we should have provided Ukraine with much more military support much earlier,” he told the Financial Times.

“I think we all have to admit, we should have given them more weapons pre-invasion. And we should have given them more advanced weapons, faster, after the invasion. I take my part of the responsibility.”

During Zelensky's September trip to the U.S., Biden announced a new $8 billion worth of military aid package for Ukraine, including a Patriot air defense battery, unmanned aerial systems, and long-range Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW) munition. However, experts say that the decisions are made too slowly, and so are the deliveries, with Washington’s nearly six-month delay in the $61 billion worth of military aid finally approved in April still taking a toll on the Donbas front line.

For now, time is on the Russian side when comparing mobilization potential, manpower, and production capacity, warned Konrad Muzyka, Poland-based analyst and director of Rochan Consulting.

“It's just impossible to predict how the war will develop because just too many factors influence the battlefield of the current stage,” Muzyka said, elaborating that the situation is similar for both sides. “Not only the ones that are quantifiable, but those are unfortunately the ones that are not quantifiable, for instance, the quality of command and control.”

Experts said that as important as the slingshots in the rears may be, the basic resources – from ammunition to armored vehicles and artillery – are crucial to holding the front line. They stressed that long-range strikes alone would not be a game changer if the Ukrainian military lacked the essentials on the battlefield.

“You need the basic stuff to actually move the frontline,” Muzyka said. “Right now ... the largest amount of problems come from the lack of men, lack of basic materials, vehicles, ammunition, even a lack of medical equipment and so on.”

“All of this sort of basic stuff, which, when we are fighting attritional warfare, this is the stuff that gets depleted,” he summed up. “This is the resource we are fighting the war of attrition in.”

However, analyst Janovsky, speaking ahead of the Ramstein meeting, said that no matter how much more manpower and firepower Moscow may have on the battlefield, “Russian advantages are not decisive.”

“If the West tomorrow decides to increase the current level of help, let’s say doubling it, it would be a huge problem for Russia.”