When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, many in the West, and in the Kremlin too, expected the Ukrainian state to crumble in weeks, if not days.

The government would flee, the state would be carved up – some lands absorbed by Russia, the rest perhaps being made into a Moscow-dominated puppet state. The war might continue, but it would be an insurgency in an occupied country, so the experts said.

They were wrong, and part of the reason they were wrong is that they had so little knowledge and understanding of Ukraine's history and its long battle to shrug off the shackles of Russian domination.

Indeed, the Kremlin's own denial of Ukrainian agency and statehood are as much the reasons for its failure to carry out regime change in Ukraine as its poor logistics and overly ambitious military plans.

At its heart, Ukrainians' fierce resistance to Russian invasion was built from the strong nationalist movement in the country.

Nationalism, of course, carries many negative associations in Western democracies with fascism. But Ukraine's nationalism is, first and foremost, an expression of the right to self-determination, not a far-right ideology, according to experts and researchers.

The present war is the latest stage of a long-running fight for freedom in Ukraine that can hardly be understood without a close look at the nationalist movements in the country throughout the 20th century, Ukrainian philosopher Volodymyr Yermolenko told the Kyiv Independent.

"We can't understand today's resistance without (knowing about) the whole bunch of other resistances that existed in Ukraine," he said.

Misleading terms

For Myroslav Shkandrij, professor of Slavic Studies at the University of Manitoba, and a leading expert on the topic, the Soviet narrative is mainly responsible for the flawed vision of Ukraine's historical fight for independence.

"The Soviet narrative since World War II has been focused on linking Ukraine and Ukrainians' desire for independence and freedom to the atrocities of World War II," Shkandrij told the Kyiv Independent.

But within Ukraine, the struggle for independence has been a long one over many generations and is a struggle for freedom, he said.

"So Ukrainians see nationalism in a positive light," Shkandrij added.

Nationalism in Ukraine, historically and traditionally, was always associated "with freedom, with democracy, with national liberation," adds leading U.S. historian Alexander J. Motyl.

"True nationalism is about the state of a nation," Motyl told the Kyiv Independent. "If you read the American Declaration of Independence in 1776, that could have been written by Ukrainians."

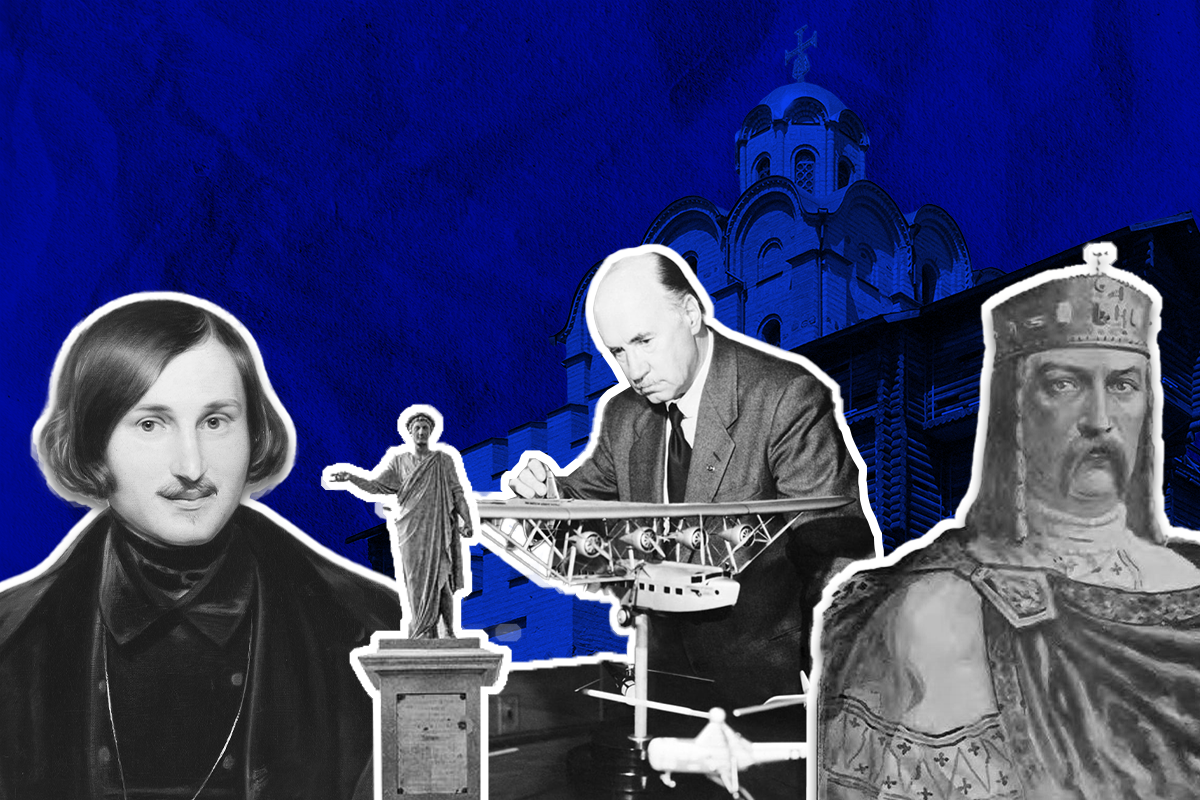

First state, and the Martyrs of Kruty

"Wars are nation builders," Motyl said. "A war forces people to choose sides because once you're invaded, you need to choose a side."

Ukraine's first attempt to exist as an independent state in modern times came at the end of the World War I, when Ukrainians saw a political window of opportunity after the 1917 February Revolution in Russia, which led to the abdication of Emperor Nicholas II.

Mykhailo Hrushevsky, a key figure in the Ukrainian national movement, was elected as the head of the newly-formed Ukrainian Central Rada in Kyiv.

The Central Rada was an organization and culture committee that took on more and more power, and soon gained authority over a good part of today's Ukraine. In Russia, the newly formed Provisional Government recognized this Ukrainian "regional government" at first.

Soon, another revolution struck Russia. The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, took power in Moscow.

The Bolsheviks grew increasingly intolerant of the Ukrainian state, even though it remained aligned with Russia.

In January 1918, the Bolsheviks entered Ukraine and moved on to Kyiv after proclaiming in Kharkiv the creation of the Ukrainian People's Republic of Soviets, a communist puppet state.

The Central Rada didn't have enough troops to stop the Bolshevik takeover. But Ukrainians' heroic resistance to Moscow domination was still to be seen, such as at the Battle of Kruty – a small town in Chernihiv Oblast to the east of Kyiv.

There, a detachment of roughly 400 Ukrainian students and cadets engaged a much larger Bolshevik force. Half of the Ukrainian cadets were killed in the battle, and another 27 were shot after being captured as revenge for their resistance. They would become celebrated as the first martyrs for the cause of national independence.

Despite losing the battle, the students and cadets were able to slow down Russian advances, allowing Ukraine's Central Rada to sign an armistice and alliance with the Central Powers.

A month later, with the help of Germany and Austria-Hungary, Ukrainians were again in control of Kyiv.

Different brands of nationalism

Despite retaking Kyiv, and holding it for nearly a year, the period that followed, known as the war for independence, saw Ukrainians and Poles at each other’s throats over control of Galicia while Kyiv was being attacked by the Bolsheviks – all against the backdrop of Ukraine's own civil war.

The years of fighting left Ukraine devastated until representatives of Russia and Poland signed a peace treaty in 1921, leaving Ukraine without a state of its own, and control of Ukrainian lands carved up between Bolshevik Russia, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and Romania.

Despite the defeat, these years were formative for the diversity of the Ukrainian nationalism movement, said Shkandrij.

"There were Marxists and Socialists in 1917-1921 who fought for independence," he said.

"They were called nationalists, even though they were Marxists and communists, in fact, and social democrats."

It would also see the beginning of Ukraine's organized nationalist movement, which started in 1919 with veterans from these wars who joined the ranks of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army.

"If you look at the Ukrainian organized nationalist movement from 1919 to 1955, for most of the period, except for two years when it flirted with fascism, it was essentially authoritarian or moralist, democratic or apolitical for about 33 years," Motyl said.

Demonizing Bandera

People usually associate Ukrainian nationalism with the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, or OUN, and its military wing, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, known by its Ukrainian acronym of UPA. The groups formed in the southeastern part of interwar Poland, today's western Ukraine, according to U.S. historian Trevor Erlacher.

And the first name that comes to mind when discussing this period is that of Stepan Bandera (1909-1959), one of Ukraine's most controversial figures, who is celebrated or hated – depending on who's talking.

Motyl believes that's because Bandera was both made into a symbol of the nationalist movement by the Ukrainians and because he was a threat to the Soviets, which made him very easy to demonize.

However, his influence over modern-day nationalism and Ukrainian society has been greatly exaggerated by Russia to discredit post-EuroMaidan Ukraine, scholars argue.

"Nobody cares about the real Bandera," Yermolenko said. "Nobody reads his texts anymore, nobody believes in this hierarchical and far-right ideology, which existed in the 1930s."

That's not Ukraine's current ideology, he said. "Ukraine's current ideology is much more horizontal, dependent on specific communities, specific people, much more decentralized, much more self-organized."

And it's clear that people who call themselves Banderites do not share his ideologies and probably have never read any of his writings, Yermolenko said.

"It's like wearing a Che Guevara T-shirt without knowing who Che Guevara was. (It's) just because it looks nice, and (Bandera is) a symbol of the underground resistance to the Soviets."

OUN and UPA

The groups associated with Bandera, the OUN, and its military wing, the UPA, themselves have a controversial legacy.

The OUN was founded in 1929 and attracted students and veterans from the Ukrainian Galician Army who wanted to fight oppression from Poles and Soviet Ukraine.

The organization was first led by Yevhen Konovalets, who was a veteran of the war for independence in Ukraine between 1917 and the early 1920s.

After the Soviet secret police killed him with an exploding chocolate box in 1938, the organization in 1940 split into two factions: the OUN-B, led by Bandera following his release from a Polish prison in 1939, and the OUN-M, led by Colonel Andrii Melnyk.

In February 1941, the larger and more violent faction, the OUN-B, made a deal with leaders of German military intelligence to form two battalions of special operation forces, Ukrainian historian Serhii Plokhy, director of the Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard University, says. One battalion was among the first German troops to enter Lviv on June 29, 1941.

The next day, Bandera proclaimed Ukraine's independence.

But Germany had other plans for Ukraine, and the Nazis turned on the Bandera faction, arresting its members and Bandera himself, whom they told to denounce his proclamation.

Bandera refused and was sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Germany, where he spent most of the World War II. Two of his brothers were arrested and died in Auschwitz.

The OUN-M tried to take advantage of the situation by setting up expeditionary groups in central and eastern Ukraine, but by early 1942 the Germans had started to hunt them down.

The OUN-B and the UPA would later face three enemies, the Germans, the Poles, and the Soviets.

Volyn Massacre

Erlacher argues that the OUN-B was an example of fascism as an organization with followers "who commit mass violence in the name of national rebirth," referring to the ethnic cleansing of Poles in Volhynia.

In the spring and summer of 1943, UPA members massacred thousands of Poles throughout Volhynia in Nazi-occupied Poland, an area that is now part of western Ukraine.

Some Ukrainians were also killed by Poles in retaliation, but most of the victims were Poles.

Plokhy estimates that the number of Ukrainians killed may vary between 15,000 and 30,000, while the estimates for the Polish victims vary between 60,000 and 90,000.

In 2016, Poland's Parliament recognized the killings as genocide, a term that Ukraine denies.

Grzegorz Rossolinski-Liebe, a Bandera biographer and historian at the Free University of Berlin, said in an interview with Deutsche Welle that he had found no evidence that Bandera, who was in a German concentration camp at the time, supported or condemned "ethnic cleansing" or killing Jews and other minorities.

It was, however, important that people from OUN and UPA "identified with (Bandera)," he said.

Bandera never returned to Ukraine after being imprisoned by Nazi Germany in 1941 and released in 1944. He was killed in 1959 by the KGB.

His name has since been heavily weaponized by Russian propaganda, and he became Moscow's favorite boogeyman when calling for Ukraine's so-called "denazification."

The UPA and Bandera were turned into symbols by the Soviets because they resisted, according to Motyl. The UPA had close to 100,000 soldiers in 1944 and was fighting behind the Soviets' line, disrupting the Red Army communications.

"They were a formidable military force through 1947-1948," Motyl said.

"And at some point, again, within the popular discourse in Ukraine, but also amongst the members of the old and new part, they began referring to themselves as Bandera people."

So it made sense for the Soviets to focus on Bandera's movement, as it was a threat, according to Motyl. The Soviets were very fearful of what he was doing because he maintained relations with the movement in Ukraine until 1954-1955, despite being abroad.

Pogroms

In Russia, Ukrainian nationalism is associated with anti-Semitism, and the Kremlin's propagandists often point to the Lviv pogrom of 1941, an outbreak of anti-Jewish violence that began on the afternoon of June 30 and ended on the evening of July 1.

Instigated by the German occupiers, the wave of violence saw the spontaneous participation of the non-Jewish local civilian population and officers of the newly formed OUN-B.

The discovery in city prisons of the bodies of Soviet prisoners, victims of mass shootings committed by the NKVD (People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs), the forerunner to the KGB (Soviet Security Service), during the first days of the war, was used by Nazi propaganda: Lviv Jews were blamed for the NKVD shootings, which resulted in the pogrom.

For Motyl, however, calling the nationalist movement anti-Semitic is a crude generalization, as it wasn't anti-Semitic in its ideology and practice.

"Obviously, there were anti-Semitic Ukrainians," he said, adding that some Ukrainian nationalists collaborated with the Nazis.

But for many Ukrainians, the issue wasn't racial but rather political, Motyl said. "The question was: Are they, or are they not, loyal to Ukraine?"

"The (nationalists) weren't out to exterminate, they were out to combat their political enemies," he said while acknowledging the presence of anti-Semites in the ranks of the OUN.

"To put it a little crudely, but not inaccurately: Ukrainians were peasants and Jews were kind of the middle class and the upper class were either Poles or Russians," he said.

When the peasant class rebels, it tends to attack the middle class first, before the larger authority, Motyl said, which explains the animosity against some of the Jewish population at the time.

A very Ukrainian phenomenon

Ukraine's nationalist heroes are thus no angels, but their main defining and uniting feature is their unbreakable commitment to the struggle for an independent state, scholars agree.

Ukrainians will generally choose heroes that are strong, forceful, and that don't break easily, Shkandrij explained. "That's why Bandera, as an unbreakable force, a person who never gave up – that's why they would find that fight attractive."

For Yermolenko, this heritage is important because it created a kind of warrior image, even though it might now be associated with fascism in Western societies.

"(But) I think it is wrong to associate this image of the warrior and warrior ethics with fascism," Yermolenko said, "because you can find the same ethics in France's anti-Nazi resistance movement."

Rather, in Ukraine, nationalism is associated with the idea that "you should fight, that you should not accept evil, that you should resist, and you should be strong as steel."

Shkandrij agrees and also explains the self-organizing nature of Ukrainian resistance to Russian colonialism.

"If you look back on the history of spontaneous and mass uprisings, there's a clue there to how Ukrainians have always had to behave because their elite has been removed, has been arrested, has been killed off over several generations."

The heroes will also be taken from these ordinary people who fought very hard or for a cause they believed in, Shkandrij adds.

"It's a phenomenon that is very Ukrainian."