WARNING: This article contains descriptions of graphic scenes.

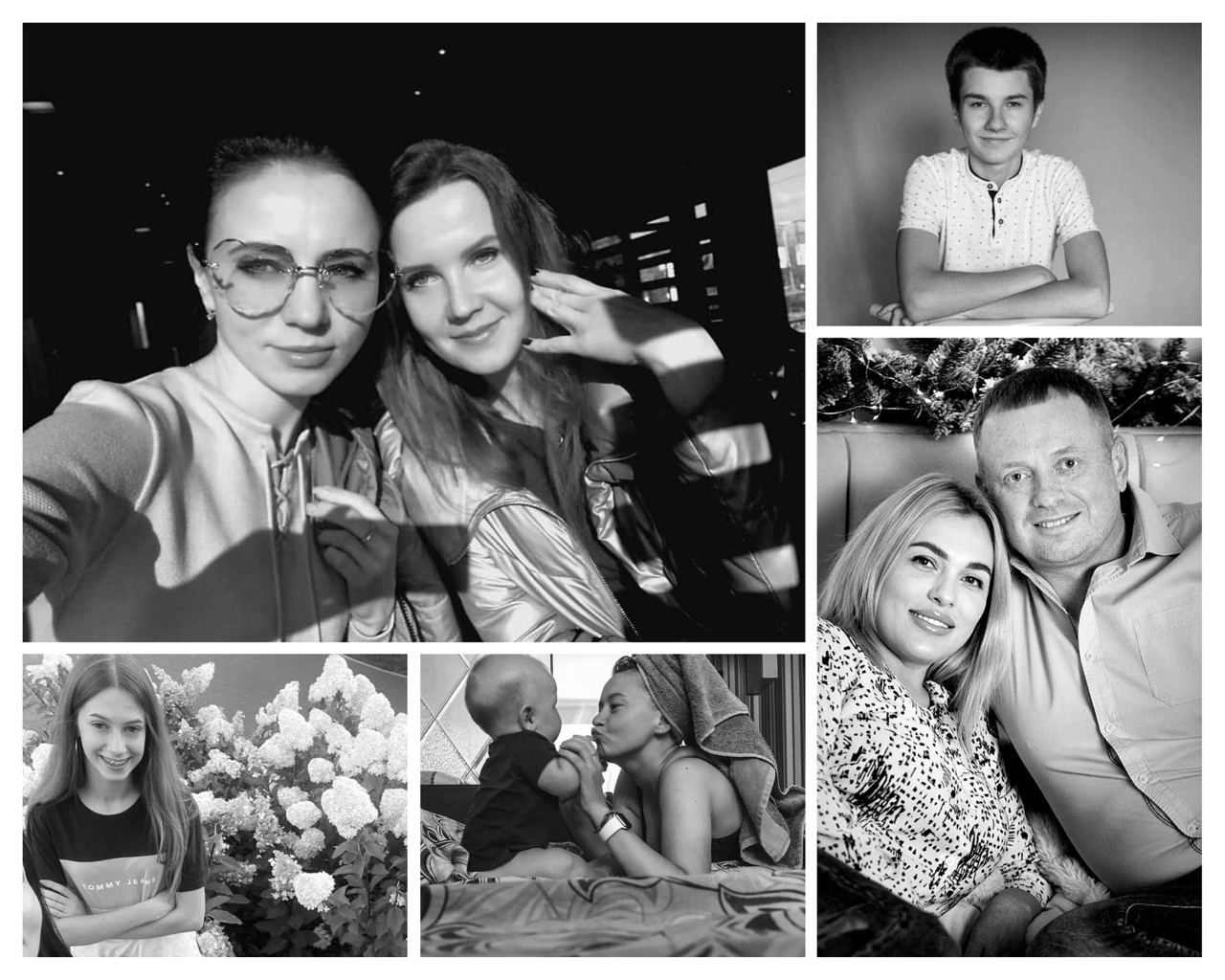

Anna Kotova was chatting with her sister on a video call, admiring her image on the screen. It was her 19th birthday, and for the first time in a while, she was feeling good about how she looked.

“I used to dye my hair a lot, and then I realized my natural hair had grown out, and I liked it so much. I had long eyelashes, and I looked so good,” Kotova recalls.

Then, in an instant, everything went dark. “The missile hit right after I thought that.”

It was Jan. 14, 2023, the day when Russia unleashed one of its deadliest attacks on Ukraine, striking an apartment building in Dnipro and killing 46 people.

"I didn't see or hear anything, like the missile flying… There was none of that,” Kotova says. “At some point, I felt that I was thrown back, and that was it. My brain just stopped working. I don't remember anything at all, just darkness."

"I don't remember anything at all, just darkness."

Kotova was among the 79 people injured in the strike. She lost one eye and endured numerous operations to remove all the shards of glass from her body. She is currently receiving laser treatment to minimize the scars left on her face and body.

Psychologists say that, like Kotova, the thousands of Ukrainians who have survived brutal Russian attacks since Feb. 24, 2022 have been left not just with lasting scars on their bodies, but long-term damage to their mental health from the trauma of their experiences.

And their number is steadily growing, as Russian attacks have been wounding civilians almost every day since the start of the full-scale war.

For Kotova, the day the Russian Kh-22 missile destroyed her home split her life into “before and after,” with no possibility of a return to the way things were before.

“You live one day at a time because you are still scared of what tomorrow might bring,” Kotova told the Kyiv Independent. “You also didn’t expect that it would happen then, that a missile would hit your house, that it would happen to you, and that you would suffer such injuries.”

“When I lived in Dnipro, I stopped reacting to the air raid alarms over time. If it hits, it hits. But back then, I just couldn't imagine the consequences.”

‘Is this my face?’

Kotova and her boyfriend had moved to Dnipro from now-occupied Sievierodonetsk in Luhansk Oblast on the very day the full-scale invasion began. They rented a spacious apartment with their friends. However, when their friends relocated to another city, the couple began searching for a smaller place.

They never found one.

“On the morning of Jan. 14, everything started very well,” Kotova recalls. “I woke up to flowers and a new phone, and everything was wonderful. I couldn't have imagined something so horrible could happen after just a few hours.”

The explosion occurred around 3 p.m., as Kotova and her boyfriend were preparing to host some guests.

Shortly after the blast, Kotova’s boyfriend found her on the kitchen floor. He told her he could not see her eyes and her whole face, only blood and glass shards.

“I remember that when I touched my face with a towel, it felt like minced meat. There was nothing left. It was so slippery and unrecognizable,” she says.

“I started to panic and asked, 'Is this my face?' My boyfriend told me not to touch anything and that everything would be fine. I fell silent and didn't say anything else.”

As they escaped the building, they were able to see the scale of the attack and realized how lucky they had been to survive: “I heard people's screams, sirens, and loud noises. I remember that it was very frightening,” Kotova says.

But for her, the most challenging part was yet to begin.

She was taken to a local hospital, where doctors placed her in a coma and performed surgery.

“I woke up on the 15th or 16th (of January). I tried to move, but a doctor came up to me and told me that they had removed my eye…” she says tearfully.

“I had a breakdown. I couldn't breathe on my own, couldn't swallow or talk, and tears started to flow… I couldn’t see anything; I was just lying there, realizing … I no longer had one eye.”

Numerous other operations, lengthy treatments, and the fitting of eye prosthetics in Austria followed. Kotova currently resides in Czechia but often travels to Kyiv for laser treatment. With time, she has learned to look at herself in the mirror without crying, but she cannot forget that horrible January strike.

Her 20th birthday this year, naturally coinciding with the attack’s anniversary, was one of her hardest days.

“I knew I was in Czechia, and it was safe there. But I still had this fear that it would happen again.”

“(Shortly after the attack) I simply didn’t want to continue treatment. I didn’t understand how much more there was to endure or why it happened to me. I thought that maybe it would have been better if I had stayed (meaning died) in that house and not suffered further,” Kotova says.

“(But) I (have come to) truly value life because when you are on the brink of losing it, you hold on to everything you can to ensure it doesn’t happen again.”

A thirst for revenge

In mid-October 2022, Ukrainian soldier Viktor Hanych left the front lines to spend a short vacation with his parents in Kyiv. It was the first time in a while that Hanych, who voluntarily joined the military shortly after the invasion started, had seen his parents.

The whole family first gathered at Hanych’s grandmother’s home before returning to his parents’ cozy apartment on Zhylianska Street in Kyiv.

They talked about “everything in the world” and soon fell asleep, tired but happy to be together again, Hanych recalls.

“I woke up to a couple of explosions and quickly told (my parents) to get ready to go to the shelter,” he says, adding that they did not hear the air raid siren that night, and his parents usually reacted to them.

“They had an (underground) parking area right near the house where they hid from attacks,” he says.

Hanych was the first one to leave the apartment. He told his parents he would hold the door for them and wait outside. He also recalls being very calm, as he was used to explosions while fighting in embattled Kherson and Donetsk oblasts.

Just as he reached the first floor, the building was hit by a Russian drone.

“It landed right in their apartment,” Hanych says. “As a soldier, I realized what had happened. But the hardest part was the waiting.”

"It landed right in their apartment."

Although the attack occurred in the early morning, Hanych only identified the bodies of his parents at around 2 p.m. that day.

It was the day Russia launched its first-ever attack on Kyiv using Iranian-made Shahed-136 attack drones. Apart from Hanych’s parents, the bodies of two more civilians, including a six-month pregnant woman, were found under the rubble of the apartment building.

“If it wasn’t for my comrades' support…” Hanych says, adding that he had felt a “thirst for revenge” but was thankfully stopped by his fellow soldiers. After participating in fierce battles near now-occupied Bakhmut, Hanych returned to civilian life to care for his grandmother.

To this day, he tries to avoid going to Zhylianska Street, where his parents’ home once stood. “It’s excruciating,” Hanych says.

“I think those who experience something similar become fatalists but also begin to cherish and love this life even more. I felt exactly that.”

‘We no longer have a home’

The four-room apartment in Sumy was the setting for decades of sorrow and joy in the lives of resident Diana Nazarevska and her family.

But now it is gone, destroyed in a Russian attack.

“It was my grandmother's apartment. My mother grew up there, and later, when I was about three years old, we moved there with my parents,” Nazarevska, 28, says. “It was also where I started building my own family with my husband.”

“That apartment held the memories of my family, of my father, when he was still alive.”

On March 13, Nazarevska, her husband, and their baby daughter slept peacefully when an explosion woke them up.

“It was the first Shahed drone targeting the residential building, but it was shot down and flew past it. I picked up my daughter, and we lay close to the wall,” Nazarevska recalls.

Then, she heard another drone approaching. “I grabbed my child, stood up, and didn’t even have time to run anywhere… I just realized that there was an explosion in our house.”

“I grabbed my child, stood up, and didn’t even have time to run anywhere… I just realized that there was an explosion in our house.”

“Then I started shouting for my husband, asking if he was alive. He slept very soundly and didn't understand what had happened at first.”

Amid the terrifying chaos, the family grabbed some documents, dressed their baby, and fled the apartment. As her husband opened the door to the hallway, Nazarevska was confronted with the “stench of burning and the smell of damp concrete,” which she says would likely “remain in her memory forever.”

Outside, as she saw her beloved home in ruins and fire, she also witnessed her neighbors desperately searching for their loved ones in the rubble.

“I will always remember how my neighbor’s father came running and shouting, ‘Vika!’” Nazarevska says, her voice trembling. “It was the shout you hear when someone is on the verge of hysteria. He kept screaming, but no one answered him. He shouted again, and still, no one responded.”

That night, Russia killed three people and injured 14. It also forever altered Nazarevska’s life, teaching her how fragile existence can be and how important it is to cherish every moment, even amid war.

“But we no longer have a home,” she says. “And it’s not just about the walls but the loss of a sense of basic security. For people, home generally means safety. It’s the place you go where you know everything will be okay.”

“Unfortunately, that sense of security is lost now.”