Editor’s note: The Kyiv Independent is not disclosing the full names of the soldiers introduced in the story, as they didn’t have a formal authorization to speak to the press.

DONETSK OBLAST – Mykhailo arrived at a dugout less than an hour after it was hit by Russian drones.

The 40-year-old Ukrainian soldier immediately started going through the bodies, looking for signs of life. He knew that four soldiers had been taking shelter there. Yet he saw two bodies – and no one else.

"When I got there, those two were already cold," he said. It was mid-February. The men’s limbs were torn off.

There was no time to linger around. The dugout, positioned near Russian-occupied Bakhmut in eastern Donetsk Oblast, could become a target again. Mykhailo left.

Later, he learned what happened at the dugout.

Four soldiers were on their way back to the rear from the front-line positions for a shift change and took cover in the dugout. When Russian drones hit it, two soldiers were killed, one was wounded, and one is still considered missing.

What happened next is typical for the parts of the front line that suffer from the lack of combat medics and front-line evacuation.

The wounded soldier got out of the dugout and walked to the nearest evacuation point, located a few hundred meters away, on his own.

No one arrived to check on the others until Mykhailo, a fellow soldier, looked into the dugout.

At positions as heavily shelled and close to Russian troops as this one, soldiers say that medical evacuation doesn't exist.

For Mykhailo, a soldier in Ukraine's elite 80th Air Assault Brigade fighting near the liberated village of Klishchiivka, it means that every time he goes to the positions, he doesn’t count on surviving.

"I know I am going to meet death (there)," Mykhailo, who goes by the call sign Nimy ("Mute"), said. "(Evacuation) is impossible."

The main reason for the absence of medical evacuation is simple and gruesome: The fighting is just too intense.

It can take a day or even two for soldiers to get in and out of the fiercest fighting spots – killing any hopes of medics coming to save the wounded.

Left alone at the positions, the soldiers often have to pull out their comrades on their own under heavy shelling, sometimes walking five to seven kilometers to the nearest evacuation points, where vehicles take them to makeshift hospitals.

When soldiers carry their wounded out, the group is easy to spot – and it immediately becomes easy prey to Russian first-person view (FPV) drones and artillery.

Evacuation vehicles can’t come to the positions to get the wounded out fast: They are even easier to spot, and Ukraine can’t afford to lose the sparse equipment.

The front-line units say they face a severe shortage of basic equipment such as the U.S.-made M113 armored personnel carriers and even Soviet-era BMP infantry vehicles. Dozens of servicemen from three battalions who spoke to the Kyiv Independent stressed that the deficit is so critical that in their units, which number 300 to 600 infantrymen, they only have one M113 and BMP each – jeopardizing evacuation.

The vehicles often break down due to Russian attacks or complicated terrain, adding to the shortage.

The army's Medical Forces agreed that the armored vehicles used for evacuation require "constant replenishment and are not sufficient," and said the only way to solve the issue is to get more from allies.

"Of course, it (the shortage of armored vehicles) reduces the ability to implement evacuation measures," the specialist corps said in an official response to the Kyiv Independent. "The time of medical evacuation and its duration in most cases depends on the operational situation on the battlefield."

Afraid to lose armored vehicles, commanders sometimes have to prioritize the equipment over the wounded, ordering soldiers not to drive up closer to reduce the risk of a direct hit, the interviewees say. But time is crucial to saving a life or a limb.

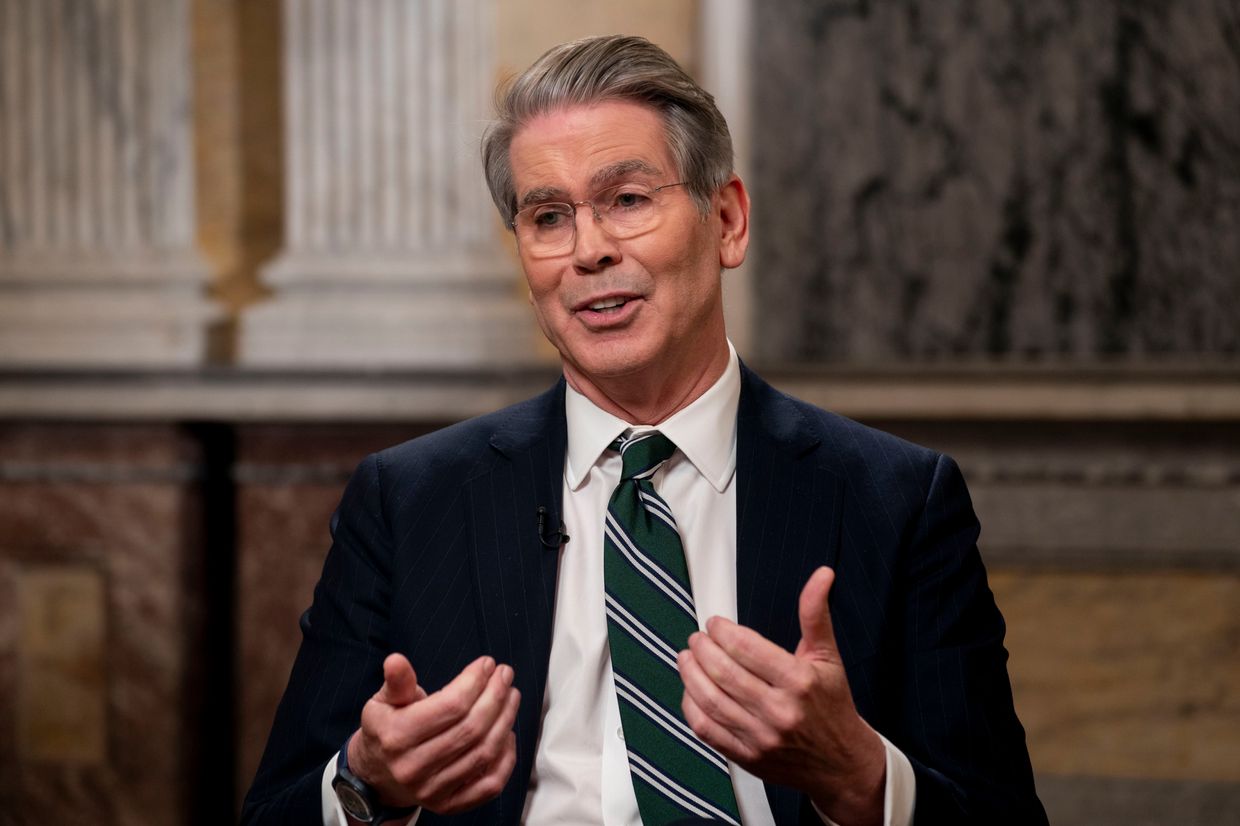

"The root problem has remained the same throughout this war – there is a deficit of armored vehicles to perform casevac missions," U.S.-based military expert Michael Kofman, a senior fellow at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, told the Kyiv Independent.

Ukraine's army is "extremely equipment-poor and medical-poor" for its size, and the problem can be traced back to 2014, according to Glen Grant, a retired U.K. Lieutenant Colonel who until recently was a defense expert at the Ukrainian Institute for the Future, a local think-tank that analyzes the country's policies.

"This goes even further back because this is a Soviet legacy where the Soviet Union didn't really expect to bring anybody back… They either keep going or they die," he said, naming Russia's approach to evacuation as an example. "Unfortunately, that attitude hasn't been sucked out of the Ukrainian system properly."

But unlike Russia, Ukraine is already facing a critical manpower shortage, especially in the infantry, as it struggles to find recruits to refill the heavy losses. Every soldier lost to poor evacuation is another that has to be replaced.

Mykhailo from the 80th brigade said that his unit had been decimated over the eight months of fighting south of Bakhmut, estimating that only 10 percent of his fellow assault soldiers remain in action – with the rest killed, wounded, or missing. Knowing he has little chance of being evacuated if wounded, Mykhailo thinks his chances to survive are small.

"I'm just doing my job the best I can," Mykhailo, the father of two, said in tears. "If I will be killed in the field…," he paused and caught up with breathing, "for Ukraine, I am ready."

'Calling artillery on yourself'

Junior Sergeant Iryna, a 26-year-old who goes by her call sign Wild, wears a GoPro camera when heading to dangerous front-line missions.

The former company commander of Ukraine's 67th Separate Mechanized Brigade does it because she is concerned that she could be sued for making what could be perceived as a wrong decision on evacuation.

The choice between risking their own soldiers' lives to evacuate the wounded and halting the mission to avoid further casualties is a tough call for commanders that almost always comes with guilt afterward.

Iryna sometimes watches the GoPro footage of an October day when she had to call off an evacuation of a wounded friend deployed on the Kreminna front, trying to see if she could have done anything differently.

On that day in the fall of 2023, Iryna and three others headed into the forest near the Russian-occupied town of Kreminna in Luhansk Oblast to pull out three wounded soldiers. They got two, but the third one, a commander from another company with the call sign Sailor, was too far away.

It was clear to Iryna's team that going closer to Sailor would be "suicidal" due to the incessant shelling. She had to call off the evacuation and leave him.

"It was either we save these guys that we have now or lose everyone," Iryna said.

Hours later, Sailor died on the spot where he was wounded.

"You have to be cold-minded in war," she said. "Quick decisions can save a lot of lives."

Another time, she recalls, when evacuation was impossible, the soldiers had the final request: to hit their positions with artillery.

Around the same time, in autumn 2023, Iryna recalled, seven soldiers were stuck under the rubble of a dugout after Russian shelling. When they finally received an order to withdraw, it was too late. The outnumbered Ukrainian soldiers were buried inside the position that had just collapsed, and the fighting was too intense for anyone to come and dig them out.

Russian troops soon reached the dugout.

"(One of the guys stuck in the dugout) was saying, 'There are (Russian soldiers) above me, I won't make it out – call the artillery on me,' and I am the commander, so you need to make the decision," Iryna said, recalling that moment.

"Either you call (artillery), and you essentially kill them, or you somehow keep the situation under control for a while, send a support group so that they can clear it and try to get the guys out."

Iryna ordered smaller shells to be fired at the position to "destroy a maximum number (of Russians) above but not harm our guys, who were buried underneath."

But it was still impossible to get anywhere close to them.

The next thing she heard on the radio was Russian soldiers trying to mimic her comrades. To this day, she doesn’t know what happened to the seven soldiers. Officially, they are missing in action.

Her unit, then led by 36-year-old veteran soldier Oleh, had encountered a similar incident in March 2023 when they were deployed near Bakhmut. Oleh, now a platoon commander with the same brigade, told the Kyiv Independent about a last-ditch rescue mission that failed, leaving 23 men stuck on the front line.

They also tried to call artillery on themselves, saying that Russian soldiers were only 10 meters away and they had no chance of fighting them off.

The artillery didn’t hit the positions. Then came the silence. No one answered the radio anymore. Oleh and others believe that everyone in the group was killed. The bodies could not be retrieved.

"Each of them wanted to live. Each of them was afraid of dying," said Oleh, who goes by the call sign Tsvyk. He blamed himself for losing the 23 comrades, and it took a heavy toll on him, he added.

Evacuation orders

Multiple company and platoon commanders across the front line said they have also suffered heavy losses due to the higher command's decisions to send men to defend the positions for "as long as they can," in places where withdrawal and evacuation weren't possible.

Soldiers often perceive such commands as mistakes, and say they cause avoidable casualties and reduce morale.

The defense and fall of Avdiivka is a recent example. The situation gradually worsened in the small industrial city just outside of occupied Donetsk, forcing Ukraine to withdraw in mid-February.

Western experts and many Ukrainian soldiers interviewed by the Kyiv Independent said the evacuation would not have been as chaotic if the decision had been made a few weeks earlier.

The price of the last-minute evacuation was heavy. The soldiers had to withdraw through a poorly prepared thin path with mines lying around and under heavy shelling west of the city.

Some soldiers were given the order to withdraw at any cost, leaving the wounded and fallen comrades behind.

Other soldiers have described similar experiences they had during the fall of Bakhmut in May 2023. Days before the fall, Oleh’s unit was ordered to go to the embattled western part of the city.

Fearing that it would be a suicide mission, the soldiers refused the order. They worried that they only received instructions on how to get inside the city on the verge of falling – but nothing concerning evacuation. Multiple local commanders blamed their leadership’s lack of knowledge of the situation on the ground and what they perceived as their unwillingness to listen to their advice.

But the officers stress that even late withdrawals may not have been as fatal if the units deployed on that front-line sector had enough ammunition to allow for the arrival of evacuation vehicles.

Shortage of ammunition, equipment undermines evacuation

Ukraine’s critical lack of ammunition also undermines the effectiveness of front-line evacuation.

Jakub Janovsky, a Prague-based analyst at the Oryx OSINT project, underscored that ammunition plays a crucial role in evacuation. If there was enough, it may have been possible to temporarily suppress the enemy with artillery and then risk a rescue mission, he explained.

"If you don't have that ammunition, that (rescue mission) immediately gets much more dangerous than it would otherwise be (in addition to equipment shortage)," Janovsky said.

The priority list changes with the battlefield situation, but Kyiv is currently asking Western allies for additional air defense equipment, electronic warfare equipment, artillery, ammunition, combat aircraft, and drones, Ukrainian Ambassador to NATO Natalia Galibarenko told the Kyiv Independent.

Ukraine has rightfully placed ammunition as the top priority since a higher firing rate could lead to less demand for evacuation, said Anton Pyzhykov, head of the Procurement Department at Serhiy Prytula Charity Foundation, which fundraises money for Ukraine's military.

Retired U.K. Lieutenant Colonel Grant, however, stressed that ammunition shortage should signal that the medical side needs more attention, prompting higher demand for armored vehicles for efficient evacuation.

"Military is a system. If you have any weak areas, the system breaks – and medical is one of the key parts of the system," Grant said. "We're at war. The government has got to take responsibility for identifying how to sort out the weak areas."

The issue with the lack of armored vehicles like M113s for evacuation "lies somewhere between the right equipment not being requested, and the right equipment not being provided in sufficient numbers," according to military analyst Kofman.

"Part of the issue is the continued focus on high-end capabilities instead of basic systems and platforms that are needed in large numbers to sustain Ukraine's war effort and exist in Western stocks because we are talking about primarily Cold War period equipment that's decades old," he said.

In a commentary to the Kyiv Independent, Ukraine's Defense Ministry said it had included armored vehicles that support evacuation in the needs list shared with Western allies but did not disclose the exact number of requested or received vehicles. While not calling it a shortage, the ministry agreed that there is always "a demand" for them, as domestic production is limited and the losses constantly need to be replenished.

Observing the past months of military aid pledges and delivery, military analyst Janovsky from the Oryx OSINT project said Western nations have focused more on ammunition, possibly distracting them from other needs such as equipment.

Western nations have delivered over 2,000 infantry fighting vehicles and armored personnel carriers, including nearly 190 Bradley and about 960 M113, since the full-scale war began in February 2022, according to Oryx.

Roughly 1,000 more were pledged, though Janovsky stressed that not all the pledges are made public, with certain countries likely wanting to keep their arms stockpile a secret.

While agreeing with the direness of Ukraine's ammunition scarcity, Janovsky insisted that evacuation would significantly improve if Ukraine's major ally, Washington, provided at least half its M113 armored personnel carriers currently in storage.

The U.S. has about 13,000 M113 armored personnel carriers, including 5,000 actively being used and 8,000 in storage, according to the International Institute for Strategic Studies' The Military Balance 2023 book. Oryx says that the U.S. has thus far delivered around 600.

It can take a few weeks to months for an M113 to be delivered after the pledge, along with the spare parts, according to Janovsky. Even after the pledge is made, issues sometimes arise with the delivery cost – further delaying the transfer of the equipment, he added.

Domestic political issues such as the U.S. Congress blocking Ukraine aid leave future Western support uncertain.

Pentagon spokesman Charlie Dietz confirmed the U.S. knows about Ukraine's struggle with vital equipment such as Bradley.

"Given the ongoing equipment shortages that Ukraine is facing, the needs for these are noticed, and specific numbers and timelines are subject to strategic considerations and ongoing discussions with Ukrainian and allied partners," Dietz told the Kyiv Independent. "However, we are fully aware of the urgency of the situation and are working diligently to ensure timely support as feasible."

With equipment lacking, Ukraine's military heavily relies on regular cars and pickup trucks to conduct evacuations.

Cars can beat bulky armored vehicles by speed and quietness, but they can’t maneuver through thick mud and break down more often – especially when driving through thin roads heavily struck by drones and artillery.

Commanders on the ground say it's an endless race to keep repairing the cars, often from the soldiers' own pockets or through public fundraisers run by volunteers.

Lack of experienced medics

However unpleasant it may be, the harrowing scream of the wounded is a reassuring factor, the medics say. Worse is if they are silent and slowly losing consciousness.

The so-called "golden hour" window, the first 60 minutes to provide medical care for the best chance of survival, is rarely achieved on the front line.

It could take hours – or worse, days – for the wounded to get to the medics.

If the wounded are lucky enough to make it to the evacuation point and get medical help, they face other issues, such as strained and sometimes inexperienced medics.

Vitalii, 46, who goes by the call sign King, served as a medic in the 42nd Separate Mechanized Brigade when it was deployed on the northeastern Kreminna axis front in June 2023.

The unit was inexperienced and the casualties were catastrophic, he said. It put enormous pressure on the medics, most of whom had some training but no real experience in medicine. Ukraine's Medical Forces confirmed that "there is a need for qualified medical personnel" in the military.

Vitalii admitted that he and his fellow medics may have been too slow since everything was new to them. They had to take care of up to 300 wounded soldiers on the toughest days. He wasn’t prepared for it – neither in terms of skills, nor mentally.

"I thought I was stronger,” Vitalii said. "I wanted to see a psychologist or just get wasted (after the shifts)."

The lack of experienced medics, especially surgeons who can conduct difficult surgeries in front-line areas, is critical, according to experts and front-line medics. They have called for a system encouraging more doctors to join the military to save the wounded.

"I definitely wasn't ready for this," said Vitalii.

______________________________________________________

Note from the author:

Hi, this is Asami Terajima, the author of this article.

Thank you for reading our story. I had an idea to write about the brutal reality of front-line evacuation after losing a friend, who lived about 30 minutes after a fatal injury, in November 2023. There were no combat medics around, and the roads were too terrible to even attempt an evacuation. I hate to think if anything could have changed the reality if the situation was different – but I know there are plenty of such stories across the front line.

To help the Kyiv Independent tell more stories that would otherwise not be told, please consider supporting us by becoming our member.